Why did Napoleon rule for 100 days? "One Hundred Days"

Defeat in the Franco-Russian War of 1812 led to the collapse of Napoleon's empire and in 1814, after the entry of the anti-French coalition troops into Paris, Napoleon abdicated the throne and was exiled to the island of Elba.

During his exile on Elba, Napoleon I closely followed the events in France and the progress of the Congress of Vienna, which summed up the victorious wars of the anti-French coalition. Knowing the dissatisfaction of the French with the rule of Louis XVIII and the disputes between the victorious powers, Napoleon tried to seize power again.

On February 26, Napoleon, together with a group of comrades, sailed to France and five days later landed in the south of the country. King Louis XVIII sent an army against Napoleon, which, however, went over to the side of the ex-emperor. On March 13, Napoleon issued a decree restoring the Empire and on March 20 entered Paris victoriously. The king and his court moved from the capital to Ghent in advance. From March 20, 100 days of Napoleon's re-rule begin.

The Allies, frightened by the news of Napoleon's return to power, created the seventh anti-Napoleonic coalition. On June 18 at Waterloo, Napoleon's army was defeated, and on June 22 he abdicated the throne again. After leaving France, Napoleon voluntarily arrived on the English warship Bellerophon in the port of Plymouth, hoping to receive political asylum from his old enemies - the British.

However, Napoleon was arrested and spent the last six years of his life in captivity on the island of St. Helena, where he died in 1821. In 1840, Napoleon's remains were transported to France and reburied in the Les Invalides in Paris.

Soviet historian Evgeny Tarle wrote with inimitable irony: “The government and Parisian press close to the ruling spheres moved from extreme self-confidence to complete loss of spirit and undisguised fear. Typical of her behavior during these days was the strict sequence of epithets applied to Napoleon as he advanced from south to north.

The first news: “The Corsican monster has landed in Juan Bay.”

Second news: “The cannibal is coming to Grasse.”

Third news: “The usurper has entered Grenoble.”

Fourth news: "Bonaparte occupied Lyon."

Fifth news: “Napoleon is approaching Fontainebleau.”

Sixth news: “His Imperial Majesty is expected today in his faithful Paris.”

This entire literary gamut fit into the same newspapers, with the same editors, for several days.”

"The Devil Pays or Bonnino Returns from Hell from the Island of Elba." Caricature from 1815

Caricature of Louis XVIII (the king tries to pull on Napoleon Bonaparte's boots)

"Jump from Paris to Lille." The ill-fated French king Louis XVIII, suffering from gout, limps, flees from Napoleon. Caricature from 1815

“Indigestible pie” (Louis XVIII is lying under the table, at the table from left to right is the Prussian King Frederick Film III, Alexander I, Wellington, the Austrian Emperor Franz I. Napoleon crawls out of the pie). Caricature from 1815

"Sunset". Climbing out, Napoleon tilts the cap to extinguish the candles, on which the French king sits. Louis XVIII loses his balance, dropping the Constitutional Charter, and his crown is stolen by the imperial eagle. Caricature from 1815

"Great maneuvers or the Rascal marches to the island of Elba." 1815 cartoon depicting Napoleon's exile on the island of Elba

"Robinson of the Island of Elba". Caricature from 1815

Caricature of Napoleon on the Elbe

"Swing". On the left are the Prussian, Austrian and Russian monarchs sitting on a swing, on the right is Bonaparte. He weighs more than all the monarchs of the anti-Napoleonic coalition. The French king Louis XVIII fell from a swing. Caricature from 1815

"The Barber of the Elbe" A French soldier shaves Louis XVIII and exclaims: "It's finished! You're shaved!" The king bleats: “What soap!” (The soap says "Imperial Essence"). Beneath Louis' feet lies the Constitutional Charter. Caricature from 1815

"The Fate of France" The Order of the Legion of Honor weighs more than all the monarchs of the anti-Napoleonic coalition combined. Caricature from 1815

"Napoleon returned from Elba." Author Karl Karlovich Steuben (1788–1856). E. Tarle: “On the morning of March 7, Napoleon arrived in the village of Lamur. Troops in battle formation were visible in the distance ahead... Napoleon looked through a telescope for a long time at the troops advanced against him. Then he ordered his soldiers to take the gun under their left hand and turn the muzzle into the ground. “Forward!” - he commanded and walked ahead right under the guns of the advanced battalion of the royal troops lined up opposite him. The commander of this battalion looked at his soldiers, turned to the adjutant of the garrison commander and said to him, pointing to his soldiers: “What should I do? Look at them, they are pale , like death, and tremble at the mere thought of having to shoot at this man." He ordered the battalion to retreat, but they did not have time. Napoleon ordered 50 of his cavalrymen to stop the battalion preparing to retreat. “Friends, don’t shoot!” the cavalrymen shouted. “Here is the emperor ! The battalion stopped. Then Napoleon came close to the soldiers, who froze with their guns at the ready, not taking their eyes off the lone figure in a gray frock coat and triangular hat approaching them with a firm step. “Soldiers of the fifth regiment!” was heard among the dead silence. “Do you recognize me?” » - "Yes Yes Yes!" - they shouted from the ranks. Napoleon unbuttoned his coat and opened his chest. “Which of you wants to shoot your emperor? Shoot!” Eyewitnesses to the end of their days could not forget those thunderous joyful cries with which the soldiers, having disrupted the front, rushed to Napoleon. The soldiers surrounded him in a close crowd, kissed his hands, his knees, cried with delight and behaved as if in a fit of mass insanity. With difficulty it was possible to calm them down, form them into ranks and lead them to Grenoble."

"Brought by Freedom, Napoleon was greeted with enthusiasm by both the people and the army." Caricature from 1815

Return from Elbe. Illustration from the book "Life of Napoleon Bonaparte" by William Milligan Sloane (Sloane, William Milligan, 1850-1928)

Jules Vernet. Return of Napoleon from Elba

Joseph Beaume. Napoleon leaves Elba and returns to France on February 26, 1815

Pierre Vernet. Return of Napoleon from Elba. 1815

English caricature of Marshal Ney, who went over to Napoleon's side. Ney was convicted by the Bourbon court and executed in December 1815. E. Tarle: “Coming out in front of the front, he [Ney] grabbed the sword from its sheath and shouted in a loud voice: “Soldiers! The Bourbon cause is forever lost. The legitimate dynasty that France has chosen for itself ascends to the throne. The Emperor, our sovereign, must henceforth reign over this beautiful country." Shouts of "Long live the Emperor! Long live Marshal Ney!" his words were drowned out. Several royalist officers immediately disappeared. Ney did not interfere with them. One of them immediately broke his sword and bitterly reproached Ney. "What do you think should have been done? “Can I stop the movement of the sea with my two hands?” Ney answered.

Caricature of Napoleon's escape from the island of Elba

A caricature of Napoleon standing up and King Louis XVIII turning upside down. 1815

More about how it all looked 200 years ago (again according to Tarla):

"On March 20, 1815, at 9 o'clock in the evening, Napoleon, surrounded by his retinue and cavalry, entered Paris. A countless crowd was waiting for him in the Tuileries Palace and around the palace. When, from a very long distance, they began to reach the palace square, intensifying every minute and finally turning In a continuous, deafening, joyful cry, the cries of the countless crowd running behind Napoleon's carriage and the retinue galloping around the carriage, another huge crowd, waiting at the palace, rushed towards. The carriage and retinue, surrounded on all sides by a countless mass, could not move further. The guards tried in vain to clear the way. “People screamed, cried, rushed straight to the horses, to the carriage, not wanting to listen to anything,” the cavalrymen surrounding the imperial carriage later said. The crowd, like a madman (according to witnesses), rushed to the emperor, pushing aside the retinue, she opened the carriage and, amid incessant screams, carried Napoleon into the palace and up the main staircase of the palace to the apartments on the second floor. After the most grandiose victories, the most brilliant campaigns, after the most enormous and rich conquests, he was never greeted in Paris as on the evening of March 20, 1815. One old royalist later said that this was real idolatry. As soon as the crowd was hardly persuaded to leave the palace and Napoleon found himself in his old office (from where the fleeing King Louis XVIII had emerged 24 hours earlier), he immediately set about the affairs that surrounded him on all sides. The incredible has happened. An unarmed man without a shot, without the slightest struggle in 19 daysmarched from the Mediterranean coast to Paris, expelled the Bourbon dynasty and reigned again."

On May 30, 1814, a peace treaty was signed in Paris between France and the coalition powers, under the terms of which France was deprived of all the territories it had conquered at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries and was reduced to pre-revolutionary borders. The first government of Louis XVIII was headed by Talleyrand, and Marshal Soult became Minister of War. Most of Napoleonic marshals and generals retained command posts in the army; they recognized the new government, following the well-known principle “the army does not serve the government, the army serves the Fatherland.”

Louis XVIII, at the insistence of his allies, refused to restore the absolute monarchy, since this could cause a new revolution, and was forced to declare a constitution, called the Charter of 1814. It limited the power of the king to a parliament of two chambers: the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies. The Bourbons, restored to the throne thanks to the efforts of the coalition, could no longer return to absolutism. However, as Talleyrand ironically remarked, “The Bourbons have learned nothing and forgotten nothing from the past.” Together with them, thousands of emigrants returned to France and began to seek the return of their estates. Napoleonic police minister Fouche at one time had a list of 150 thousand emigrants. Some of them returned to France after the amnesty declared by Napoleon in 1801 and entered the service of the Empire. The most irreconcilable were now returning and demanding compensation for the losses they had suffered. The higher clergy demanded the restoration of church tithes and the return of property taken from the church.

The payment of pensions, the distribution of positions and orders to former emigrants, the return of remaining unsold lands to them, caused discontent among various sections of French society. Part of the bourgeoisie was dissatisfied with the flow of cheap English goods into the country. There were persistent rumors among the peasants that the lands they had bought during the revolution from the confiscated estates would still be taken away from them. Strong discontent arose in the army due to the massive dismissal of officers promoted during the revolution and the Empire. The sons of nobles who served in the armies of the interventionists were appointed to their positions.

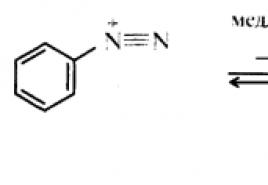

Information from France began to reach Napoleon on Elba about growing dissatisfaction with the Bourbon policies in wide circles of the population. He decided to try his luck again and regain power in the country. On March 1, 1815, on one ship with a thousand soldiers and six cannons, he left the island of Elba, landed in Juan Bay on the southern coast of France and moved towards Paris. His small detachment went along the inaccessible paths of the Alpine foothills to the north of the country. Bonaparte decided to conquer France without firing a shot. He did not want to fight the French, even if they acted under the white banner of the Bourbons, so he ordered the soldiers of his detachment not to open fire or resort to weapons under any circumstances. When it became known in Paris that Napoleon had left Elba and was on French territory, troops in the south under the command of General Miolisse were sent to cross him with orders to stop and disarm Bonaparte’s detachment. However, either Napoleon's detachment moved very quickly, or General Miolisse, who had served under the emperor for a long time, walked too slowly, but they did not meet on the way. Napoleon and his soldiers reached Grenoble unhindered.

Here large military forces under the command of General Marchand were sent against him. It was impossible to further avoid a collision with the royal troops and Napoleon moved towards rapprochement with them. Once within their line of sight, he gave the command to his soldiers to shift their guns from their right to their left hands and keep them down, thereby indicating that they were not going to fire. Having stopped his detachment, Napoleon went to meet the royal soldiers alone, without weapons and without guards. Approaching them within rifle range, he unbuttoned his uniform and shouted: “Soldiers, do you recognize me? Who wants to shoot their emperor? I'm putting myself under your bullets." It was a very risky move, but it turned out to be the right move. With shouts of “Long live the Emperor!” a detachment of royal soldiers in full went over to Napoleon's side. At the head of an already quite large army, Napoleon entered Grenoble, whose residents greeted him with stormy greetings.

With a rapid march, replenished with garrisons of small towns that went over to his side, Napoleon's army approached Lyon. Louis XVIII arrived in this second largest city in France, hoping to block Napoleon's path with the help of an army of 30,000. But seeing that the situation was becoming more and more dangerous for him, he hastily fled the city. The entire garrison and the entire population of Lyon went over to the side of the emperor without any resistance. From Paris, the king sent troops against Napoleon under the command of one of the most famous commanders of France, Marshal Ney, who was known in the imperial army as “the bravest of the brave.” Ney promised Louis XVIII to bring Napoleon in an iron cage. He could not forgive the emperor for the failure of the senseless, in his opinion, campaign against Russia in 1812 and the loss of the entire army there, so he quite sincerely intended to fulfill his promise. The army subordinate to him was immeasurably stronger than Napoleonic's, but the soldiers and officers openly declared their desire to go over to the side of the emperor. When both armies met, Ney was forced, following his troops, to go over to Napoleon's side. Now nothing could stop the emperor’s advance to Paris.

In Paris, a large, hand-written poster with a mocking content appeared on the Vendôme Column: “Napoleon to Louis XVIII. King, my brother, don’t send me any more soldiers, I already have enough of them.” This ironic inscription revealed the truth that virtually the entire army had gone over to Napoleon's side. Louis XVIII and his family fled in panic from Paris under the protection of coalition troops. Public opinion in the capital turned out to be in favor of Napoleon. The white flag was torn from the Tuileries Palace and replaced with a tricolor one; inside the royal residence, carpets depicting white Bourbon lilies were quickly replaced with carpets with golden bees, a symbol of the Empire. Thousands of Parisians took to the streets of the city to greet the emperor. On March 20, 1815, Napoleon entered the Tuileries Palace. These twenty days of March, when a handful of people, landing on the French coast, conquered an entire country in three weeks, without firing a single shot, without killing a single person, were the most amazing pages in the history of Europe, France and in the life of Napoleon.

Both French and Soviet historians see the essence of this event in the fact that the overwhelming majority of the French people, faced with the need to make a choice between the bourgeois power of Napoleon and the feudal power of the Bourbons, came out in support of the first. This was the French response to the Bourbons’ attempts to eliminate those transformations in the country that had been carried out during the years of the revolution in the interests of broad sections of the population. Napoleon himself these days repeatedly emphasized that the people and the army brought him to Paris, and made broad promises of political and social reforms.

The government formed by Napoleon after returning to Paris included Carnot, a famous member of the Jacobin Committee of Public Safety, as Minister of the Interior. As a republican by conviction, he refused to serve Napoleon after the proclamation of the Empire, but in these days of Napoleon's liberal promises, he offered him his cooperation. Napoleon entrusted the Ministry of Police to Fouche, which, according to contemporaries, meant introducing treason into his own home.

Napoleon saw that the previous regime of individual power was no longer possible, so although he restored the Empire, he tried to make it liberal. He invited Benjamin Constant, the leader of the liberal opposition, whom he had persecuted at one time, to the Tuileries Palace and instructed him to draw up additions to the constitution. The "Additional Act", prepared by Benjamin Constant, was a compromise with the Charter of 1814. The property qualification for voters was reduced, but the House of Peers was retained. The plebiscite system was restored. Soon the newly elected legislative institutions began their work.

It was obvious that Napoleon could maintain his power and the support of the people only without exposing them to the horrors of a new war. Therefore, he turned to all European powers with a proposal for peace on the terms of the “status quo”. He stated that he renounced all claims, France does not need anything, it only needs peace. Napoleon sent Alexander I the secret treaty of England, Austria and France, forgotten in a hurry by Louis XVIII, which they had concluded at the Congress of Vienna against Russia and Prussia. But this did not help him split the new, seventh, coalition that formed against him and was legally formalized on March 25. Almost all European states were ready to launch a new campaign against Napoleonic France. The declaration, adopted by the heads of European states, declared Napoleon an outlaw and an “enemy of humanity.” Napoleon hoped that his father-in-law, the Austrian Emperor Franz, would take into account the interests of his daughter and his grandson, but a letter from Vienna said that his wife was not faithful to him, and his son would never be given to his father and would be raised as an enemy of Napoleon. Whether Napoleon wanted it or not, France had to fight again.

Numerous coalition forces of European monarchies from different directions moved towards the borders of France. Napoleon decided to go to meet the enemy in Belgium. His plan was to prevent the Prussian army of Blucher and the Anglo-Dutch army under Wellington from joining, but, following his proven tactics, to defeat them separately. At first, the campaign developed successfully. On June 16, Ney attacked the British at Quatre Bras and defeated them, but the British still managed to escape. On the same day, at Ligny, Napoleon inflicted a heavy defeat on Blucher's troops and ordered Marshal Grouchy with 35 thousand soldiers to pursue them. With his main forces, Napoleon moved against Wellington, who had dug in near the village of Waterloo. On June 18, this last battle of the many years of war began. Wellington, with his “bulldog grip,” as they called it, was difficult to dislodge from the positions he occupied, but the French were already gaining the upper hand everywhere and had almost achieved victory when suddenly a rapidly advancing mass of soldiers appeared on the right flank.

Napoleon hoped that it was his Marshal Grouchy who stopped pursuing Blucher's troops, turned back and was approaching the site of the main battle. A similar situation arose in 1800 at the Battle of Marengo, then the situation was saved by the divisions of General Dese, who, having heard the cannonade of the battle of the main French forces against the Austrian troops, contrary to the order of Bonaparte, who sent him to pursue the Austrians in a different direction, returned to Marengo. Having attacked the enemy with fresh forces, his divisions brought victory to the French in this battle. In 1800, General Dese could show a similar initiative in relation to General Bonaparte, who was equal in position with him. During the years of the Empire, everything changed and Marshal Grushi, even having heard the cannonade of the battle, contrary to the insistence of his officers, did not dare to disobey, and, fulfilling the letter of the emperor’s order, continued to pursue the Prussians on the same course, not noticing that their main forces broke away from him and moved towards Waterloo . The messenger sent to Grouchy by the chief of the French staff, Marshal Soult, was intercepted by the British. Upon learning of this, Napoleon noted with indignation that the former chief of staff, the late Berthier, would have sent a hundred messengers. The Prussian army under the command of Blucher attacked the French regiments awaiting the arrival of their own, demoralized them and put them to flight.

An episode has been included in historical literature showing the steadfastness and dedication of the old Napoleonic guard under the command of Cambronne and its loyalty to the emperor. Having formed a square, she calmly, like a powerful battering ram, made her way through the enemy ranks. The English colonel offered the guard honorable terms of surrender. Then Cambronne uttered a phrase that became famous: “...The Guard dies, but does not surrender!” The Battle of Waterloo ended in the complete defeat of Napoleon's army.

On June 21, Napoleon returned to Paris, he was ready to continue the war. Carnot proposed mobilizing the National Guard and fighting under the walls of Paris. But the majority of members of the House of Representatives and the House of Peers did not support him. At the suggestion of Lafayette, the chambers declared their meetings continuous, and an attempt to dissolve them a state crime, thereby predetermining the abdication of the emperor. Napoleon was forced to submit to them and on June 22 for the second time and now he abdicated the throne forever. After his abdication, the Chamber of Deputies appointed a provisional government chaired by Fouché for peace negotiations with the coalition. On July 3, 1815, he signed a capitulation with Wellington and Blücher. The Bourbons returned to the throne, Fouche became minister of police for the fifth time.

Napoleon did not want to become a prisoner of the Bourbons, so he went to Rochefort to the seashore and on July 15 surrendered “to the mercy of the winner” to his most important enemy - England, having reached one of the English ships in the roadstead. This time the British assigned him a place of exile on the inaccessible island of St. Helena", located off the coast of Africa, from where it was necessary to sail for at least a month to get to any of the European ports. In this way, the British protected themselves from a possible repetition of the events known as “Napoleon’s 100 days.” If on the island of Elba Napoleon was free and retained his status as emperor, then on the island of St. Helena he was a prisoner of the British. On this island, Napoleon lived under the supervision of local English authorities for another 6 years and died in 1821. While on the island, Napoleon wrote his memoirs, which are a valuable source on this period of French and European history. In 1840, Napoleon's ashes were transported from St. Helena and reburied with honors in Paris.

Napoleon, without the slightest struggle, walked from the Mediterranean coast to Paris in 19 days, expelled the Bourbon dynasty and reigned again. But he knew that again, as in his first reign, he did not bring peace with him, but a sword, and that Europe, shocked by his sudden appearance, this time would do everything to prevent him from gathering his forces.

Napoleon understood that after 11 months of the Bourbon constitutional monarchy and some freedom of the press, the urban bourgeoisie expected from him at least some minimum of freedoms; he needed to quickly illustrate the program that he was developing, moving towards Paris and playing the revolutionary general. The class of French society that won during the revolution and whose main representative and strengthener of victory was Napoleon, that is, the big bourgeoisie, was the only class whose aspirations were close and understandable to Napoleon. It was in this class that he wanted to feel supported, and in his interests he was ready to fight. “I don’t want to be king of the jacquerie,” Napoleon said to the typical exponent of bourgeois aspirations at this moment, Benjamin Constant. The emperor ordered to call him to the palace to resolve the issue of liberal state reform, which would satisfy the bourgeoisie, prove the newly-minted freethinking of Emperor Napoleon and at the same time calm down the Jacobins who had raised their heads.

On April 6, Constant was brought before the emperor, and on April 23, the constitution was ready. Benjamin Constant simply took the charter, that is, the constitution given by King Louis XVIII in 1814, and made it a little more liberal. The electoral qualifications for voters and those elected were greatly lowered, but still, in order to become a deputy, you had to be a rich person. Freedom of the press was somewhat more ensured. Preliminary censorship was abolished, and crimes of the press could henceforth be punished only in court. In addition to the elected chamber of deputies (of 300 people), another was established - the upper chamber, which was to be appointed by the emperor and be hereditary. Laws had to pass through both houses and be approved by the emperor.

Napoleon accepted the project and the new constitution was published on April 23. Napoleon did not really resist the liberal creativity of Benjamin Constant. He only wanted to postpone the elections and the convening of the chambers until the question of war was resolved, and then, if there was a victory, it would be clear what to do with the deputies, and with the press, and with Benjamin Constant himself. For the time being, this constitution was supposed to calm minds. But the liberal bourgeoisie had little faith in his liberalism, and the emperor was very much asked to speed up the convening of the chambers. Napoleon, after some objections, agreed and appointed the “May Field” for May 25, when the results of the plebiscite to which the emperor subjected his new constitution were to be announced, the banners of the National Guard were to be distributed and the meetings of the chamber were to open. The plebiscite gave 1,552,450 votes for the constitution and 4,800 against. The ceremony of distributing banners (it took place not on May 26, but on June 1) was majestic. At the same time, on June 1, meetings of the newly elected chamber opened.

The people's representatives had only been meeting for a week and a half, and Napoleon was already dissatisfied with them. He was absolutely incapable of living with any limitation on his power or even with any sign of independent behavior. The Chamber chose as its chairman Languine, a moderate liberal, a former Girondin, whom Napoleon did not really like. It was also impossible to see any opposition in this - Languine definitely preferred Napoleon to the Bourbons - and the emperor was already angry and, accepting the most submissive and very respectful address from the Legislative Corps, said: “Let us not imitate the example of Byzantium, which, pressed on all sides by barbarians, became the laughing stock of posterity, engaging in abstract discussions at the moment when the battering ram smashed the city gates.” He hinted at a European coalition, hordes of which rushed from all sides to the borders of France. He accepted the address of the people's representatives on June 11, and the next day, June 12, he went to the army for the last battle with Europe in his life.

3 Battle of Ligny

Of the 198 thousand soldiers that Napoleon had on June 10, 1815, more than a third were scattered throughout the country. For the upcoming campaign, the emperor had directly in his hands about 128 thousand with 344 guns in the guard, five army corps and a cavalry reserve. In addition, there was an emergency army (national guard, etc.) of 200 thousand people, half of which were not uniformed, and the third were not armed. If the campaign had dragged on, then, using the organizational work of his Minister of War Davout, he could have collected about 230-240 thousand more people with the greatest efforts. The British, Prussians, Austrians, and Russians have already deployed about 700 thousand people at once, and by the end of the summer they could have deployed another 300 thousand.

Before Napoleon were the British and Prussians, the first of all the allies to appear on the battlefield. The Austrians also hurried to the Rhine, but they were still far away. Wellington with the English army stood in Brussels, and the Prussian army under the command of Blucher was scattered on the Sambre and Meuse rivers, between Charleroi and Liege.

On June 14, Napoleon began the campaign by invading Belgium. He quickly moved into the gap that separated Wellington from Blucher and rushed at Blucher. The French occupied Charleroi and fought across the Sambre River. But Napoleon's operation on the right flank slowed down somewhat: General Bourmont, a royalist by conviction, long suspected by the soldiers, fled to the Prussian camp. After this, the soldiers became even more suspicious of their superiors. To Blücher, this incident seemed a favorable sign, although he refused to accept General Bourmont, who had betrayed Napoleon.

Napoleon ordered Marshal Ney to occupy the village of Quatre Bras on the Brussels road on June 15 in order to pin down the British, but Ney, acting sluggishly, was too late to do this. On June 16, a great battle between Napoleon and Blucher took place at Ligny. Victory remained with Napoleon; Blucher lost more than 20 thousand people, Napoleon - about 11 thousand. But Napoleon was not happy with this victory, because if not for the mistake of Ney, who unnecessarily delayed the 1st Corps, forcing him to take a vain walk between Quatre Bras and Ligny, he could have destroyed the entire Prussian army at Ligny. Blucher was defeated and thrown back (in an unknown direction), but not destroyed.

4 Battle of Waterloo

On June 17, Napoleon gave his army a break. Around noon, Napoleon separated 36 thousand people from the entire army, placed Marshal Grouchy over them and ordered him to continue pursuing Blucher. Part of Napoleon's cavalry pursued the British, who the day before tried to pin down the French at Quatre Bras. But the rain heavily washed out the roads, and the pursuit had to be stopped. Napoleon himself with the main forces united with Her and moved north, in a direct direction to Brussels. Wellington, with all the forces of the English army, took a position 22 kilometers from Brussels, on the Mont Saint-Jean plateau, south of the village of Waterloo. The forest of Soigny, north of Waterloo, cut off his escape route to Brussels. Wellington fortified himself on this plateau. He was going to wait for Napoleon in this very strong position and hold out, no matter the cost, until Blücher managed, having recovered from defeat and received reinforcements, to come to his aid.

By the evening of June 17, Napoleon approached the plateau with his troops and saw the English army in the distance in the fog. Napoleon had approximately 72 thousand men, Wellington 70 thousand when they faced each other on the morning of June 18, 1815. Both were expecting reinforcements and had a solid reason to wait for them: Napoleon was waiting for Marshal Grouchy, who had no more than 33 thousand people; The British were waiting for Blucher, who after the defeat at Ligny had about 80 thousand people left, and who could appear with 40-50 thousand ready for battle.

Already from the end of the night Napoleon was in place, but he could not launch an attack at dawn, because the rain had loosened the ground so much that it was difficult to deploy the cavalry. The emperor toured his troops in the morning and was delighted with the reception he received: it was a completely exceptional outburst of mass enthusiasm, not seen on such a scale since the time of Austerlitz. This review, which was destined to be the last review of the army in Napoleon's life, made an indelible impression on him and everyone present.

Napoleon's headquarters were first at the farm du Caillou. At 11 o'clock in the morning, it seemed to Napoleon that the soil was dry enough, and only then did he order the battle to begin. Strong artillery fire from 84 guns was opened against the left wing of the British and an attack was launched under the leadership of Ney. At the same time, a weaker attack was launched by the French for the purpose of demonstrating at the castle of Hougoumont on the right flank of the English army, where the attack met the most vigorous resistance and encountered a fortified position.

The attack on the British left wing continued. The murderous struggle lasted for an hour and a half, when suddenly Napoleon noticed, in a very great distance in the northeast near Saint-Lambert, the vague outlines of moving troops. At first he thought it was Grouchy, who had been sent orders early in the night and then several times during the morning to hurry to the battlefield. But it was not Grouchy, but Blucher, who had escaped Grouchy’s pursuit and, after very skillfully executed transitions, had deceived the French marshal, and was now rushing to the aid of Wellington. Napoleon, having learned the truth, was still not embarrassed; he was convinced that Grushi was following on the heels of Blucher and that when both of them arrived at the battlefield, then although Blucher would bring more reinforcements to Wellington than Grushi would bring to the emperor, the forces would still be more or less balanced, and if before Blucher’s appearance and If he manages to deliver a crushing blow to the British, then the battle will be finally won after Grusha’s approach.

Having sent part of the cavalry against Blucher, Napoleon ordered Marshal Ney to continue the attack on the left wing and center of the British, which had already experienced a number of terrible blows since the beginning of the battle. Here four divisions of d’Erlon’s corps advanced in dense battle formation. A bloody battle began to boil along this entire front. The British met these massive columns with fire and launched a counterattack several times. One after another, the French divisions entered the battle and suffered terrible losses. The Scottish cavalry cut into these divisions and cut down part of the composition. Noticing the collapse and defeat of the division, Napoleon personally rushed to the heights near the Belle Alliance farm, sent several thousand cuirassiers of General Milhaud there, and the Scots, having lost an entire regiment, were driven back.

This attack upset almost the entire d'Erlon corps. The left wing of the English army could not be broken. Then Napoleon changed his plan and transferred the main attack to the center and right wing of the English army. At 3 o'clock the La Haye-Saint farm was taken by the left flank division of d'Erlon's corps. But this corps did not have the strength to develop its success. Then Napoleon handed over to Ney 40 squadrons of the cavalry of Milhaud and Lefebvre-Denuette with the task of striking the right wing of the British between the castle of Hougoumont and La Haye-Saint. The castle of Hougoumont was finally taken at this time, but the English held out, falling in hundreds and not retreating from their main positions.

Napoleon sent more cavalry into the fire, 37 Kellermann squadrons. Evening came. Napoleon finally sent his guards to the British and himself directed them to attack. And at that very moment, screams and the roar of shots were heard on the right flank of the French army: Blucher with 30 thousand soldiers arrived on the battlefield. But the attacks of the guard continued, since Napoleon believed that Grouchy was coming after Blucher. Soon, however, panic spread: the Prussian cavalry fell on the French guard, who found himself between two fires, and Blucher himself rushed with the rest of his forces to the Belle Alliance farm, from where Napoleon and the guard had previously set out. Blucher wanted to cut off Napoleon's retreat with this maneuver. It was already eight o'clock in the evening, but still quite light, and then Wellington, who had been under continuous murderous attacks from the French all day, launched a general offensive. But Grushi still didn’t come.

The guard, having formed a square, slowly retreated, desperately defending itself through the close ranks of the enemy. Napoleon rode at a pace among the battalion of guards grenadiers guarding him. The desperate resistance of the old guard delayed the victors. In other areas, the French troops, and especially at Plancenoit, where the reserve - the Lobo corps - fought, resisted, but ultimately, exposed to attacks by fresh Prussian forces, they scattered in different directions, fleeing, and only the next day, and then only partially began to gather into organized units. The Prussians pursued the enemy all night long.

25 thousand French and 22 thousand British and their allies lay dead and wounded on the battlefield.

5 Paris. Renunciation

The defeat of the French army, the loss of almost all artillery, the approach of hundreds of thousands of fresh Austrian troops to the borders of France, the imminent prospect of the appearance of even more hundreds of thousands of Russians - all this made Napoleon’s position completely hopeless, and he realized this immediately, moving away from the Waterloo field. Outwardly, Napoleon was calm and very thoughtful throughout the journey from Waterloo to Paris, but his face was not as gloomy as after Leipzig, although now everything was really lost for him.

With Napoleon a drastic change immediately took place. He came to Paris after Waterloo not to fight for the throne, but to surrender all his positions. And not because his exceptional energy disappeared, but because he, apparently, realized that he had done his job - whether badly or well - and that his role was over. He had lost all interest and taste for activity, he was simply waiting for what future events would do to him, in the preparation of which he had already decided not to take any part.

Napoleon arrived in Paris on June 21 and immediately convened his ministers. Carnot proposed to demand from the chambers the proclamation of Napoleon's dictatorship. Davout advised simply to adjourn the session and dissolve the chamber. Napoleon refused to do this. The Chamber also met at this time and, at the suggestion of Lafayette, who had reappeared on the historical stage, declared itself indissoluble.

Throughout June 21, almost the entire night from June 21 to 22, throughout the day of June 22, in the Saint-Antoine and Saint-Marseille suburbs, in the Temple quarter, processions walked through the streets shouting: “Long live the Emperor!” Down with traitors! Emperor or death! No need for renunciation! Emperor and defense! Down with the ward! But Napoleon no longer wanted to fight and did not want to reign.

On June 22, 1815, Napoleon abdicated the throne for the second time in favor of his young son. His second reign, which lasted one hundred days, ended. A huge crowd then gathered around the Elysee Palace, where Napoleon stayed after returning from the army. “No need for renunciation! Long live the Emperor!” - the crowd shouted. Having learned on the evening of the 22nd that Napoleon had left for Malmaison, and that his abdication had been decided irrevocably, the crowds began to slowly disperse.

On June 28, the abdicated emperor left Malmaison and headed to the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. He wanted to board one of the frigates stationed in the port of Rochefort and go to America. But it was impossible to go to sea: the English squadron closely blocked the harbor. After some thought, Napoleon decided to entrust his fate to England. On July 15, 1815, he boarded the brig Hawk, which transported him to the English ship Bellerophon. Napoleon became a prisoner of the British and was then sent to the remote island of St. Helens in the Atlantic Ocean. There, in the village of Longwood, the former emperor spent the last six years of his life.

Publisher's abstract: "One Hundred Days" by Napoleon Bonaparte is one of the intriguing and fascinating episodes of European history of the 19th century. On March 1, 1815, the great exile returned from Elba and landed on the French coast. On March 20, he solemnly, amid cries of “Long live the Emperor!” enters Paris. By uniting with Marshal Ney, Napoleon becomes a threat to the fragile geopolitical balance established by the Congress of Vienna. The study of the English historian Edith Saunders is a striking example of Northern European historiography of the Napoleonic wars. It combines strict scientific thoroughness with a figurative manner of presentation, a detailed description of the battles of Ligny, Quatre Bras and Waterloo with episodes from the biography of the French emperor. The book is supplied with appendices and will be of interest to both specialists and history buffs.

Content

1. Congress of Vienna; return of Napoleon from the island of Elba; trip to Paris

2. Relations between Napoleon and Marie Louise; defeat of Marshal Ney; fall of Louis XVIII

3. Napoleon's reign is resumed; hostility of powers; war between Austria and Joachim Murat; secret mission in Vienna

4. Life in the capital; news about Marie Louise; visit to Malmaison

5. Captain Mercer's troops land at Ostend; Napoleon and the liberal constitution; Mercer in Strytham; Murat's defeat

6. Weakening of Napoleon's forces; military plans; May field

7. Military preparations; opening of the French parliament; Napoleon arrives in the army; the location of the troops of England and Prussia; eve of invasion

8. French invasion of Belgium; Ney commands the left wing; the right wing under the command of Grouchy attacks the Prussians

9. In Brussels; Napoleon's orders on the 16th; the beginning of the Battle of Ligny; Ney against Wellington at Quatre Bras; d'Erlon's erroneous march

10. Fierce Battle of Ligny; continuation of the battle at Quatre Bras; d "Erlon in Ligny; Napoleon's victory; Ney's defeat; the Prussians return to Wavre

11. Inaction of Napoleon on the 17th in the morning; Pears pursues the Prussians; Wellington's retreat; the French are advancing

12. Eve of the Battle of Waterloo; Wellington's troops in position; Napoleon's breakfast; review of French troops

13. First phase of the battle; Pears in Valen; second phase; unsuccessful attack on Wellington's left center line

14. Third phase of the battle; largest cavalry charge; Prussians entering the battle

15. Fourth phase of the battle; capture of La Haye Sainte; fifth phase; attack of the Imperial Guard; Ziethen's arrival; withdrawal of the French army

16. The Prussians are pursuing the French; Napoleon is running; his crew and other property were seized; his trip to Paris

17. Napoleon and his ministers; Lafayette's actions; Napoleon is forced to abdicate; he leaves Paris for Malmaison; Napoleon's surrender; end of hostilities

Napoleon Bonaparte: paradoxes of the triumphant. (A. Bauman)

Notes

Congress of Vienna;

return of Napoleon from the island of Elba;

trip to Paris

Napoleon's return from the island of Elba in 1815 was the most desperate undertaking of his entire career. Together with a handful of adventurers, he landed on the French coast, from which less than a year before he had been expelled, and against all odds he marched from Cannes to Paris, beginning his campaign as an outcast and ending with the triumphant recovery of his lost title of French Emperor. Such a step required exceptional strength and presence of mind. It was necessary to withstand long marches, repel enemy troops and skillfully manage one’s own, it was necessary to write and print proclamations, and make speeches. Napoleon directed everything with victorious ease, gaining popularity and fame everywhere as a master of all trades. It is not surprising that the majority of Europeans, amazed by this magnificent tour de force (march of strength - French), decided that he had returned for a long time and it was pointless to fight such a powerful genius. Just three months later, the same man, the great Napoleon, conducted the campaign at Waterloo in a completely different manner, making mistake after mistake, as if in a sudden darkness. It was as if he were a different person, as if fate had deliberately catapulted him back to the pinnacle of power, removing all difficulties from his path and providing happy occasions at every turn, only so that the reckoning prepared for him over the past twenty years would seem less bitter. Invested with supreme power, he proclaimed himself emperor, a man who was honored and celebrated by others. But as soon as he reached this position, his luck turned away from him, and the history of the next three months, when the most intense efforts brought him nothing but results opposite to those desired, suggests that he, far from directing the events of his victorious days, and all historical figures, was led by forces over which he himself had no control.

In March 1815, prospects for lasting peace in Europe opened up. The long war with France, in which England found itself drawn in for more than twenty years(1), ended last spring, and Emperor Napoleon, all-round defeated, was forced to abdicate and exchange the great empire he had conquered for control of the small island of Elba off the coast of Italy(2 ). Instead of him, the elderly, unambitious His completely Christian Majesty Louis XVIII (3) now ruled, whose main desire was to maintain good relations with the powerful powers, to whom he owed his return to the throne of France. A few weeks earlier, a treaty of peace and friendship had been signed between Great Britain and the United States of America, which had been at war since 1812(4). The most blissful calm replaced the widespread storm that had raged so furiously since the outbreak of the French Revolution, and it seemed that the states needed only patience and the development of industry to restore.

Monarchs and diplomats had been gathering in Vienna since September to sort out tangled European affairs(5). It was a meeting of representatives of the dynasties in search of a compromise on the basis of which future diplomacy could protect their ruling houses from the dangers of war and revolution. They hardly thought about the fate of the little people, with the exception of the question of slavery, which was of great interest to England. However, peace was certainly a matter of prime necessity in those times, and one could at least hope that its permanent establishment would soon be followed by an improvement in the conditions of life for mankind as a whole.

Although peace was so desired, the basis for it was difficult to find, and there were several critical moments at the Congress of Vienna when it seemed that war was about to break out again between impatient and impoverished countries. The allies easily found common ground while they were bound together by the goal of defeating Napoleon, but now that the danger was over, their interests were divided, each of them felt the need to pursue his own, and the conferences were stormy. The problem that separated them most of all was the fate of Poland. Tsar Alexander I, supported by Frederick William III, King of Prussia (6), wanted to make Poland united under his protection. He was sharply opposed by the Austrian Emperor Francis I and the British Commissioner Castlereagh (7). Talleyrand, a representative of Louis XVIII, who hoped to improve the position of France by siding with Great Britain and Austria, energetically added fuel to the fire. Finally, Alexander and Frederick William began to threaten others so belligerently that Talleyrand managed to persuade Castlereagh and Metternich, the minister of the Austrian Emperor, to sign a secret treaty of cooperation between Great Britain, Austria and France against Russia and Prussia (8).

Bonaparte spent nine months and 21 days on the Elbe. The payment of the imperial allowance in the amount of 2 million francs was entrusted to Louis XVIII. However, the French monarch was in no hurry to fulfill this obligation. Napoleon needed money to pay his personal guards, which he felt urgently needed. From the continent, reports came to Elbe about general dissatisfaction with the return of the Bourbons - a restoration imposed by Talleyrand and the heads of the victorious powers. There were also dissatisfied people among the royalists. The subject of their dissatisfaction was the policy initiated by Louis XVIII of integrating the state structures created by Napoleon into the old monarchical system of government, while many royalists hoped for a complete and unconditional return to the pre-revolutionary state structure. The era of Napoleon's rule was a period of rapid growth of the middle class. The reforms of the provisional government and Louis XVIII, aimed at limiting the influence of the middle class, caused growing protest.

Napoleon closely followed events in France. In full accordance with his forecasts, the reduction of the territory of the empire to the size of pre-revolutionary France caused a wave of discontent. The indignation of the French was caused by stories about the unceremoniousness that the nobility who returned from emigration demonstrated in their treatment of veterans of the Grand Army and representatives of the lower classes. The situation in neighboring states, exhausted by almost continuous military operations, was also restless.

The conflicting plans of the members of the Sixth Coalition became the cause of acute diplomatic conflicts between the former allies. Among the Parisian royalists and representatives of the Allied powers there was talk of Bonaparte's exile to St. Helena and, possibly, his physical elimination. Under these conditions, Napoleon decided to return to the continent. According to his calculations, the return of many tens of thousands of French prisoners of war from Russia, Germany, Great Britain and Spain allowed him to quickly form a new army consisting of well-trained veterans.

On February 26, 1815, after waiting for a British Royal Navy vessel whose task was to patrol the coastal waters of the Elbe to briefly go on another mission, Napoleon and his supporters (according to various estimates, from 600 to 1200 people) left the island in a flotilla of small ships. They managed to travel the entire route undetected and landed on the French coast a few days later. This small detachment was armed with two artillery pieces. Addressing his soldiers, Napoleon declared that they would enter Paris before his son's birthday (March 20th) without firing a single shot.

After a six-day trek along icy mountain roads, Napoleon reached Grenoble. On the road to Grenoble, near the village of Lafrais, the travelers were met by soldiers of the fifth army infantry regiment. Separating from his companions, Napoleon headed towards the soldiers of the French army, who were ordered to shoot at the emperor. Bonaparte approached within pistol shot range. The excited soldiers were in no hurry to carry out the order. According to eyewitnesses, Napoleon opened his greatcoat and shouted: “If anyone decides to kill his own emperor, let him shoot now!” The soldiers lowered their weapons and shouted “Long live the Emperor!” and joined his squad. In Grenoble, events took a similar turn. The army that left the city consisted of 9,000 soldiers and officers; It was armed with thirty guns.

News of the approaching imperial army preceded Napoleon, and everywhere, with the exception of royalist Provence, a warm welcome awaited him. In Leon he was received with imperial honors. The townspeople removed the governor appointed by Louis XVIII from his post and came out to greet Napoleon. Soon, several of his former military leaders joined his troops. They ignored the order received from Marshal Michel Ney to bring him to Paris “in a cage, like a wild animal.” Soon Marshal Ney himself with an army of six thousand went over to Napoleon’s side. Keeping his promise, Bonaparte led troops to Paris on March 20th. The Parisians greeted the emperor. Not a single soldier died on the way to the capital. Initially, the royalists were unable to organize any effective resistance.

Arrival in the capital marked the beginning of the second period of the emperor's reign, which went down in history as the Hundred Days of Napoleon. Napoleon's residence became the Tuileries Palace, from which Louis XVIII fled to Ghent the evening of the previous day. On March 13, while in Lyon, Napoleon ordered the dissolution of the legislative assembly and the convening of the Champ de Mai - a general people's assembly, which was tasked with changing the constitution of the Napoleonic empire (the traditions of the May Fields go back to the Campus Martius ) - popular assemblies of the Merovingian dynasty). According to contemporaries, in a conversation with the classic of French liberalism Benjamin Constant, he said: “I’m getting old. I may be satisfied with the serene rule of a constitutional monarchy. And it will certainly suit my son.”

The work on the new Law was carried out by Benjamin Constant and agreed with the Emperor. Its result was an addition to the imperial constitution, according to which the House of Peers and the House of Representatives were formed. Membership in the House of Peers was hereditary (originally peers were appointed by imperial decree), and the House of Representatives was an elected body. The amended constitution guaranteed freedom of the press and expanded the voting rights of citizens. An amended version of the French constitution was adopted following a plebiscite held on June 1, 1815. Soon after arriving in Paris, Bonaparte began forming a government. This task turned out to be quite difficult, as representatives of the middle class chose to exercise caution, fearing further upheaval. Taking into account the fact that the leadership of the anti-Napoleonic coalition was in Vienna at that time, quick retaliatory measures could be expected from the emperor’s opponents.

The command of the Allied forces met in Vienna a week after Napoleon's arrival in Paris to develop a program of joint action in the current situation. According to Napoleon, he was ready to conclude a peace treaty if the other side so desired, but the allies did not trust him and wanted to remove him from power once and for all. Just six days before his triumphant arrival in Paris, Napoleon was declared an outlaw. A decision was made to jointly invade France. Despite hasty preparations, the Allies were able to prepare for the invasion only in May 1815.

This delay gave Napoleon the opportunity to prepare his own troops. To achieve this, all measures were taken to increase and strengthen the French armies. The troops were replenished with National Guard units and militias. However, the emperor did not want to carry out a new conscription, fearing protests among large sections of the population. By the end of May, the Northern Army (L'Armée du Nord) was formed, which was to take part in the Battle of Waterloo. Despite all efforts, the armed forces numbered approximately 300,000 people. They were opposed by a million-strong Allied army.

Bonaparte faced a choice between two strategies. He could position troops around Paris and Lyon and organize the defense of these cities, hoping to wear down the allied troops, or, on the contrary, attack superior enemy forces and try to break them into several parts. The Emperor preferred the second strategy. By organizing the defense of Paris and Lyon, most of the French territory would have been captured by the enemy almost unhindered, which, in turn, would have led to the loss of the confidence of the population on which Napoleon relied. According to the attack plan developed by the emperor, it was planned to strike the troops of the best commanders of the coalition located along the northern border of France and in the Netherlands, in particular, the army of Wellington, who took a direct part in the final defeat of Napoleonic troops. By defeating Wellington, Napoleon would not only be able to protect the weakest of his three fronts, but also undermine the morale of the enemy soldiers, expanding the camp of his supporters in France.

Early in the morning of June 15, Napoleonic troops, concentrated on the northern border of France, advanced on enemy positions. Napoleon intended to drive a wedge between the English and Prussian forces, defeat the Prussian army, and then fight the British. Ultimately, he hoped to force his opponents to the negotiating table and achieve a peace agreement that would keep him in power in his country. Initially, the French troops were tasked with occupying the city of Charleroi in the first half of the day. They managed to take the allied army by surprise. The Prussian troops stationed around Charleroi began a disorderly retreat, and although Napoleon's army failed to complete its task as planned, the results were quite satisfactory.

The next day, Napoleon again advanced deep into enemy territory. He ordered several brigades to destroy the remnants of the Prussian army or cut them off from Wellington's main forces, located north of Waterloo near Brussels. The remaining French troops began the march to Quatre Bras, the strategic crossroads of the Brussels-Charleroi and Nivelles-Namur roads. About 20,000 French troops took part in the Battle of Quatre Bras, which took place on June 16th.

Initially they were opposed by 8,000 soldiers and officers of the allied forces. The arrival of the British Third Division a few hours after the start of the battle ensured the Allied superiority in numbers. Allied losses amounted to 4,800 people, French losses - 4,000 people. Neither side managed to achieve victory, but in strategic terms, the advantage was on Napoleon's side: Wellington's troops were unable to come to the aid of the Prussian army at the Battle of Ligny. During the battle, Napoleon faced many problems. For the most part, these were difficulties in the information transmission system: orders were lost or arrived late. For this reason, in the battle of Quatre Bras he failed to solve many strategic problems. Thus, most of the Prussian troops managed to avoid defeat. Many allied units that fought at Quatre Bras also survived. Reformed, they joined Wellington's army at the Battle of Waterloo. Due to difficulties in transmitting orders, some brigades and formations of the Napoleonic army never took part in the battles.

The victory at the Battle of Ligny was the last victory in Napoleon's military career. In this battle, Napoleon's 68,000-strong army was opposed by an 84,000-strong army under the command of Prussian field marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Prince of Wallstadt. The numerical superiority of the Prussian army hardly indicated the real balance of forces. The French troops included many experienced military leaders who won dozens of battles under the leadership of Napoleon, while the Prussian army of 1815, according to researchers, was the worst army formed by Prussia in the entire history of the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars - the worst in everything that concerned manpower, equipment and organization. The losses of Prussian troops in the Battle of Ligny amounted, according to various estimates, from 12,000 to 20,000 troops killed and wounded. The number of deserters exceeded 8,000. Defeat at the Battle of Ligny prevented Wellington from holding his position at Quatre Bras. On June 17, his troops retreated north.

Napoleon, who joined Marshal Ney on the same day, ordered an offensive in the afternoon, but by this time the enemy had already abandoned their positions. The French army began pursuing Wellington's retreating troops, but this step did not bring the desired result. The pursuit of the Prussian army retreating after the defeat at Ligny also ended in failure: it unhinderedly entered the village of Wavre, providing itself with the opportunity to join Wellington’s troops, which had taken up positions at Waterloo.

The Battle of Waterloo, which took place on June 18, 1815, was the decisive battle of the last of Napoleonic campaigns. Under the command of Napoleon there were about 72,000 soldiers and officers. His army was armed with 246 artillery pieces. The Allied forces numbered 118,000 troops. The start of the battle was delayed for several hours: Napoleon waited for the ground to dry out after heavy rain that had fallen during the night (wet soil made it impossible to deploy artillery). Napoleon intended to defeat the enemy troops with a powerful blow. The troops of the Seventh Coalition had been retreating for the previous two days, and Bonaparte was planning their final defeat.

By order of the emperor, the French army attacked Wellington's troops, who had taken positions on the Mont Saint-Jean plateau. The Allies managed to repel several attacks. Among the circumstances that ultimately contributed to the French defeat were difficulties in transmitting orders and lack of awareness of enemy actions. Prussian units, arriving from Wavre in the afternoon, attacked the right flank of the French army. The Chief of Staff of the Army of the North, Emmanuel Grouchy, who had previously received orders to destroy the Prussian troops at Wavre, approached the village and engaged the Prussian Third Corps, believing that he was attacking the rearguard of a disorderly retreating enemy. At this time, the three remaining corps of Prussian troops were reorganized and marched unhindered in the direction of Waterloo to help Wellington. Thus, Bonaparte’s intention to split the troops of the Seventh Anti-Napoleonic Coalition was not realized. With a joint onslaught, the allies drove back his troops.

After the defeat at Waterloo, the victory at Wavre did not bring significant results. The troops under Grouchy's command began an orderly retreat, creating the basis for the unification of other French units. However, this army was unable to hold back the onslaught of the combined forces of the Seventh Coalition and retreated to Paris. The troops of Wellington and Blucher followed. In the last battle of the Napoleonic Wars, which took place near Issy-les-Moulineaux, Blucher's army defeated the troops of Marshal Davout. Vandam, a divisional general of the Napoleonic army, who became famous for robberies and insubordination, took an active part in this last battle. According to contemporaries, Napoleon once turned to him with the words: “If I had two people like you, the only right decision would be to force one of you to hang the other.” At the end of the twentieth century, this concept of two Vandames was realized in the feature film Double Impact. However, even Vandam's participation did not change the tide of the battle of Issy-les-Moulineaux. Shortly before this battle, in June 1815, Napoleon abdicated the throne. The defeat at Issy-les-Moulineaux prevented French troops from holding Paris and ended all hopes of maintaining Napoleonic power in France.

Napoleon hastily left Paris and tried to flee to North America, but the British command foresaw this development of events, and ships of the Royal Navy blocked French ports. On July 15, Napoleon was taken aboard the English ship Bellerophon. Over the next few months, some French fortresses continued to hold out. The campaign ended with the surrender of Longwy on September 13th. Under the terms of the treaty signed in Paris on November 20, 1815, Louis XVIII returned to the French throne, the Allies were allowed to occupy France for a period of five to seven years, and the Bonapartes were prohibited from ascending to the French throne. Napoleon went into exile on the island of St. Helena. On the initiative of the Russian Emperor Alexander I, the Holy Alliance was formed, which included Russia, Prussia and Austria. The Holy Alliance was intended, among other things, to fight revolutionary and national liberation movements in Europe. Napoleon died on Saint Helena in 1821.