Scientific achievements awards and game prizes. Biography

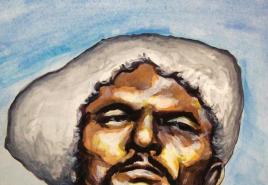

Andrey Konstantinovich Geim was born on October 21, 1958 in the city of Sochi, Krasnodar region. His parents were engineers of German origin, and Game himself considers himself European. In 1964, the family moved to Nalchik. After school in 1975, Andrei tried to enter the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute.

Despite gold medal and excellent knowledge of the applicant, the attempt was unsuccessful, the same thing played a cruel joke German origin Game. As a result, after working for a year at the Nalchik Electrovacuum Plant, Game again “stormed the capital,” this time more successfully. The guy became a student at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. In 1982.

After graduating from the Faculty of General and Applied Physics, Andrei Konstantinovich entered graduate school and in 1987 received academic degree candidate of physical and mathematical sciences at the Institute of Solid State Physics Russian Academy Sci.

Game left Russia shortly before Perestroika in 1990. Having received a scholarship from the Royal Society of England, he worked for some time at the University of Nottingham, then at the University of Bath, at the University of Copenhagen, at the University of Nijmegen, and since 2001 at the University of Manchester.

The scientist’s most famous discovery: graphene, a new generation material that has a number of unique properties, increased strength and density, high electrical conductivity and excellent thermal conductivity, and opens up new prospects in the creation of touch screens, light panels and solar panels.

The technology for creating graphene, invented by Andre Geim and his student Konstantin Novoselov in 2004, has earned scientists several awards, including the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010. By the way, Geim became the first scientist to receive not only the Nobel Prize, but also the Ig Nobel Prize, which is awarded for the most ridiculous inventions.

Andrei Konstantinovich and Michael Berry from the University of Bristol received the Ig Nobel Prize for their experiment with a levitating frog. For my scientific activity Game has received a number of awards and holds many honorary academic titles and degrees. In particular, he is a member of the Royal Society of London, an honorary doctor of Delft technical university, Swiss higher education institution technical school Zurich and the University of Antwerp, and holds the title of Langworthy Professor at the University of Manchester.

By decree of Queen Elizabeth II, on December 31, 2011, Andrei Geim was awarded the title of Knight Bachelor with the right to add the title “Sir” to his name for services to science.

As of October 2018, Andrey Geim currently lives in Holland with his wife Irina Grigorieva, heads the Manchester Center for Mesoscience and Nanotechnology and heads the department of condensed matter physics.

Sir Andrei Konstantinovich Game - full member Royal Society, fellow and British-Dutch physicist, born in Russia. Together with Konstantin Novoselov, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for his work on graphene. He is currently Regius Professor and Director of the Center for Mesoscience and Nanotechnology at the University of Manchester.

Andrey Game: biography

Born on October 21, 1958 in the family of Konstantin Alekseevich Geim and Nina Nikolaevna Bayer. His parents were Soviet engineers of German origin. According to Game, his mother's grandmother was Jewish, and he suffered from anti-Semitism because his last name sounded Jewish. Game has a brother, Vladislav. In 1965, his family moved to Nalchik, where he studied at a school specializing in English. Having graduated with honors, he twice tried to enter MEPhI, but was not accepted. Then he applied to MIPT, and this time he managed to get in. According to him, the students studied very intensely - the pressure was so strong that people often broke down and left their studies, and some ended up with depression, schizophrenia and suicide.

Academic career

Andrey Geim received his diploma in 1982, and in 1987 he became a candidate of science in the field of metal physics at the Institute of Solid State Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Chernogolovka. According to the scientist, at that time he did not want to pursue this field, preferring physics elementary particles or astrophysics, but today he is happy with his choice.

Geim worked as a research fellow at the Institute of Microelectronics Technologies at the Russian Academy of Sciences, and since 1990 at the universities of Nottingham (twice), Bath and Copenhagen. According to him, he could do research abroad and not deal with politics, which is why he decided to leave the USSR.

Work in the Netherlands

Andrey Geim took his first full-time position in 1994, when he became an assistant professor at the University of Nijmegen, where he worked on mesoscopic superconductivity. He later received Dutch citizenship. One of his graduate students was Konstantin Novoselov, who became his main scientific partner. However, according to Geim, his academic career in the Netherlands was far from smooth sailing. He was offered professorships in Nijmegen and Eindhoven, but he refused because he found the Dutch academic system too hierarchical and full of petty politics, it was completely different from the British one, where every employee has equal rights. In his Nobel lecture, Geim later said that this situation was a little surreal, since outside the walls of the university he was warmly welcomed everywhere, including his scientific supervisor and other scientists.

Moving to the UK

In 2001, Game became Professor of Physics at the University of Manchester, and in 2002 he was appointed Director of the Manchester Center for Mesoscience and Nanotechnology and Langworthy Professor. His wife and long-time collaborator Irina Grigorieva also moved to Manchester as a teacher. Later Konstantin Novoselov joined them. Since 2007, Game has become a senior fellow at the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. In 2010, the University of Nijmegen appointed him Professor of Innovative Materials and Nanoscience.

Research

Geim has found a simple way to isolate a single layer of graphite atoms, known as graphene, in collaboration with scientists from the University of Manchester and IMT. In October 2004, the group published their results in the journal Science.

Graphene consists of a layer of carbon, the atoms of which are arranged in two-dimensional hexagons. It is the thinnest material in the world, as well as one of the strongest and hardest. The substance has many potential uses and is an excellent alternative to silicon. According to Geim, one of the first applications of graphene could be the development of flexible touch screens. He didn't patent new material, because it would require a specific application and an industry partner to do so.

The physicist was developing a biomimetic adhesive that became known as gecko tape due to the stickiness of gecko limbs. This research is still in its early stages, but it already gives hope that in the future people will be able to climb onto ceilings like Spider-Man.

In 1997, Geim studied the possibility of magnetism affecting water, which led to famous discovery direct diamagnetic levitation of water, which became widely known thanks to the demonstration of a levitating frog. He also worked on superconductivity and mesoscopic physics.

On the topic of selecting his research subjects, Game said he disdains the approach of many choosing a subject for their PhD and then continuing the same topic until retirement. He changed his topic five times before he got his first full-time position, and this helped him learn a lot.

History of the discovery of graphene

One autumn evening in 2002, Andre Geim was thinking about carbon. He specialized in microscopically thin materials and wondered how the thinnest layers of matter might behave under certain experimental conditions. Graphite, composed of monoatomic films, was an obvious candidate for research, but standard methods for isolating ultrathin samples would overheat and destroy it. So Geim assigned one of his new graduate students, Da Jiang, to try to get as thin a sample as possible, at least a few hundred layers of atoms, by polishing a one-inch crystal of graphite. A few weeks later, Jiang brought back a grain of carbon in a petri dish. After examining it under a microscope, Game asked him to try again. Jiang reported that this was all that was left of the crystal. While Game was jokingly reproaching him for having a graduate student rub down a mountain to get a grain of sand, one of his senior comrades saw lumps of used tape in the trash can, the sticky side of which was covered with a gray, slightly shiny film of graphite residue.

In laboratories around the world, researchers use the tape to test the adhesive properties of experimental samples. The layers of carbon that make up graphite are loosely bonded (the material has been used in pencils since 1564 because it leaves a visible mark on paper), so tape easily separates the flakes. Game put a piece of duct tape under a microscope and found that the thickness of the graphite was thinner than what he had seen so far. By folding, squeezing and peeling the tape, he was able to achieve even thinner layers.

Geim was the first to isolate a two-dimensional material: a monatomic layer of carbon, which under an atomic microscope appears as a flat lattice of hexagons, reminiscent of a honeycomb. Theoretical physicists called such a substance graphene, but they did not imagine that it could be obtained at room temperature. It seemed to them that the material would disintegrate into microscopic balls. Instead, Geim saw that the graphene remained in a single plane, which began to ripple as the substance stabilized.

Graphene: remarkable properties

Andrei Geim enlisted the help of graduate student Konstantin Novoselov, and they began studying the new substance for fourteen hours a day. Over the next two years, they conducted a series of experiments during which the material's amazing properties were discovered. Because of its unique structure, electrons, without being influenced by other layers, can move through the lattice unhindered and unusually quickly. Graphene's conductivity is thousands of times greater than copper. Geim's first revelation was the observation of a pronounced "field effect" manifested in the presence of electric field, which allows you to control conductivity. This effect is one of the defining characteristics of silicon used in computer chips. This suggests that graphene could be the replacement that computer makers have been looking for for years.

The path to recognition

Geim and Konstantin Novoselov wrote a three-page paper describing their discoveries. It was rejected twice by Nature, with one reviewer saying that isolating stable two-dimensional material was impossible and another not seeing “sufficient scientific progress” in it. But in October 2004, an article entitled “Electric field effect in atomically thick carbon films” was published in the journal Science, making a great impression on scientists - before their eyes, science fiction became reality.

Avalanche of discoveries

Laboratories around the world began research using Geim's adhesive tape technique, and scientists discovered other properties of graphene. Although it was the thinnest material in the universe, it was 150 times stronger than steel. Graphene turned out to be pliable, like rubber, and could stretch up to 120% of its length. Thanks to research by Philip Kim and then scientists at Columbia University, it was discovered that this material is even more electrically conductive than previously established. Kim placed graphene in a vacuum where no other material could slow it down. subatomic particles, and showed that it has a “mobility” - the speed at which an electrical charge passes through a semiconductor - 250 times greater than that of silicon.

Technology race

In 2010, six years after the discovery made by Andrei Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, they were finally awarded the Nobel Prize. Then the media called graphene a “miracle material,” a substance that “could change the world.” He was approached by academic researchers in the fields of physics, electrical engineering, medicine, chemistry, etc. Patents were issued for the use of graphene in batteries, water desalination systems, improved solar powered, ultra-fast microcomputers.

Scientists in China have created the lightest material in the world - graphene airgel. It is 7 times lighter than air - one cubic meter of the substance weighs only 160 g. Graphene aerogel is created by freeze-drying a gel containing graphene and nanotubes.

The British government invested $60 million in the University of Manchester, where Game and Novoselov work, to create on its basis National Institute graphene, which would allow the country to be on par with the world's best patent holders - Korea, China and the United States, which have begun the race to create the world's first revolutionary products based on the new material.

Honorary titles and awards

An experiment with magnetic levitation of a living frog did not bring quite the result that Michael Berry and Andrei Geim expected. The Ig Nobel Prize was awarded to them in 2000.

In 2006, Game received Scientific American's 50 award.

In 2007, the Institute of Physics awarded him the Mott Prize and Medal. At the same time, Game was elected a member of the Royal Society.

Geim and Novoselov shared the 2008 Europhysics Prize "for the discovery and isolation of a monatomic layer of carbon and the determination of its remarkable electronic properties." In 2009 he received the Kerber Award.

The next Andrey Geim John Carty Award, which he was awarded by the National Academy of Sciences of the United States in 2010, was given “for his experimental implementation and study of graphene, a two-dimensional form of carbon.”

Also in 2010, he received one of six honorary professorships from the Royal Society and the Hughes Medal "for his revolutionary discovery of graphene and the identification of its remarkable properties." Geim was awarded honorary doctorates from the TU Delft, ETH Zurich, and the universities of Antwerp and Manchester.

In 2010 he became a Knight Commander of the Order of the Netherlands Lion for his contributions to Dutch science. In 2012, Geim was made a Knight Bachelor for his services to science. He was elected a Foreign Corresponding Member of the United States Academy of Sciences in May 2012.

Nobel laureate

Geim and Novoselov were awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering work on graphene. Upon hearing about the award, Geim said he did not expect to receive it this year and did not intend to change his immediate plans for this. A modern physicist has expressed hope that graphene and other two-dimensional crystals will change daily life humanity just as plastic did. The award made him the first person to win both the Nobel Prize and the Ig Nobel Prize at the same time. The lecture took place on December 8, 2010 at Stockholm University.

Andrey Konstantinovich Geim was born on October 21, 1958 in Sochi. His parents, Konstantin Alekseevich Geim and Nina Nikolaevna Bayer, were engineers, Volga Germans by nationality. From 1965 to 1975, Game lived and studied at school No. 3 in Nalchik, from which he graduated with a gold medal. After graduating from school, he tried to enter the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute (MEPhI), but they refused to admit him there because of his nationality. Therefore, he worked for one year as a mechanic at the Nalchik Electric Vacuum Plant, where his father was the chief engineer. In 1976, Geim was again rejected from MEPhI and entered the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT), where he defended his diploma in 1982. After this, Geim began working as a graduate student at the Institute of Solid State Physics of the USSR Academy of Sciences (ISSP), where in 1987 he defended his Ph.D. thesis (later in questionnaires this scientific title was mentioned as Ph.D.), after which he worked for three years as a researcher at the Institute of Microelectronics Problems and high-purity materials in Chernogolovka, created on the basis of ISTP. In Chernolovka, Game studied metal physics, which, in his own words, quickly bored him.

In 1990, Game went to the UK for an internship at the University of Nottingham and no longer worked in the USSR and Russia. In 1992 he studied science at the University of Bath, and from 1993 to 1994 he worked at the University of Copenhagen. In 1994, Geim became a researcher and, since 2000, a professor at the University of Nijmegen in the Netherlands. He received citizenship of this country, renouncing Russian and changing his name to Andre Geim. In parallel, from 1998 to 2000, Game was a special professor at the University of Nottingham.

In 2000, Geim, along with Michael Berry, received the Ig Nobel (anti-Nobel) Prize for a 1997 article that described an experiment in the field of diamagnetic levitation - the co-authors achieved levitation of a frog using a superconducting magnet. The press also noted that Game was able to create an adhesive tape that works according to the adhesion mechanisms of the gecko, and in 2001 he included the hamster “Tisha” (H.A.M.S. ter Tisha) as a co-author of one article.

In 2000, Geim and his wife received an invitation to the University of Manchester and a year later left the Netherlands, leaving a negative review of the local scientific community. He became professor of physics at the University of Manchester, a post he held until 2007. In 2002, he headed the department of condensed matter physics, as well as the Center for Mesoscience & Nanotechnology at this university. Since 2007, he has held the position of Langworthy Professor of Physics at the University of Manchester.

In 2004, Geim, together with his student Konstantin Novoselov, discovered graphene - a two-dimensional layer of graphite one atom thick with good thermal conductivity, high mechanical rigidity and other beneficial properties. In 2007, Game was awarded the Mott Prize for this discovery. international Institute physics (Institute of Physics), and in 2009 became a professor at the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. Game was awarded the 2010 John J Carty Award. National Academy USA (US National Academy of Sciences) and the Hughes Medal of the Royal Society of Great Britain.

In 2006, Scientific American included Game in its list of the 50 most influential world scientists, and in 2008, Russian Newsweek named Geim one of the ten most talented Russian emigrant scientists. In total, by 2010, Game had published more than 180 scientific works in peer-reviewed publications.

In October 2010, Geim and Novoselov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "for their seminal experiments with the two-dimensional material graphene."

After the news of the Nobel Prize being awarded to immigrants from Russia, they were invited to work in Russian innovation center“Skolkovo”, however, Game said in an interview that he had no plans to return to his homeland: “For me, staying in Russia was like spending my life fighting windmills, and work for me is a hobby, and wasting my life fussing with mice I absolutely didn’t want to.” At the same time, he called himself in an interview “a European and 20 percent Kabardino-Balkarian.” Despite his reluctance to return to Russia, he noted high quality fundamental education at MIPT: in 2006, Game said that those lobes of the brain that he lost due to alcoholic libations after exams at the institute were replaced by lobes occupied by information received at the institute, which was never useful to him. He also collaborated with the Institute of Solid State Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Chernogolovka, where they investigated the possibility of creating a graphene transistor.

Best of the day

| I am from Odessa! I'm from Odessa! Hello!.. |

In 2010, Andre Geim won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of graphene. Since then, wonder material—this is the name that has been assigned to graphene in English-language literature—has become a truly hot topic. Today, Geim's research group at the University of Manchester continues to explore two-dimensional materials and make new discoveries. The scientist presented the latest results of his work and prospects in the field of research of 2D heterostructures at the METANANO-2018 conference in Sochi. And in an interview for the ITMO University news portal ITMO.NEWS and the MIPT corporate magazine “For Science”, he talked about why you shouldn’t spend your whole life studying the same scientific field, what motivates young scientists to go into basic science and why do researchers you need to learn to present the results of your work as clearly as possible.

Andrey Geim. Photos courtesy of the Faculty of Physics and Technology of ITMO University

During your speech, you spoke about the latest results and prospects for the study of two-dimensional materials. But , if you go back, what exactly brought you to this field and what key research are you currently doing?

At the conference, I presented a report in which I called what I am now doing - graphene 3.0, since graphene is the first herald of a new class of materials in which, roughly speaking, there is no thickness. You can't make anything thinner than one atom. Graphene became a kind of snowball that caused an avalanche.

This area has developed step by step. Today people are working on two-dimensional materials, which we have known for more than ten years, and we were pioneers here too. And after that, it became interesting how to stack these materials on top of each other - I called this graphene 2.0.

We still deal with thin materials. But in the last few years I have jumped a little away from my specialty - this quantum physics, especially electrical properties solids. Now I'm working on molecular transport. We have learned, instead of graphene, if you like, to make empty space, antigraphene, “two-dimensional nothing.” Studying the properties of cavities, how they allow molecules to flow, and so on - no one has done this before, this is a new experimental system. And there are already a lot of interesting studies that we have published. But we need to develop this area and see how the properties of, for example, water change if we set restrictions ( In particular, research results were published a few months ago in the journal Science, you can also read about the work - editor's note).

These questions are not idle, since all life consists of water and it has always been believed that water is the most polarizable material known. But we discovered that near the surface the water completely loses its polarization. And this work has many applications for a large number of completely different fields - not only physics, but also biology and so on.

In one of interview You said that the history of the 20th century shows that it typically takes 20 to 40 years for new materials or new drugs to travel from an academic laboratory to mass production. Is this statement true for graphene? On the one hand, there is a lot of news about its use, on the other hand, so far about its mass use in ordinary life It's probably too early to say.

Look for yourself: all our materials that we used until recently were characterized by height, length, width - such attributes. And now, after 10 thousand years of civilization, suddenly we have found material - and not just one, but dozens - that are radically different from the Stone, Iron, Bronze, Silicon Ages, and so on. This new class materials. And this, of course, is not software, where you can write a program and become a millionaire in a few years. People will soon think that the telephone was invented Steve Jobs, and the computer is Bill Gates. It's actually 70 years of work, condensed matter physics. First, people figured out how silicon and germanium work, then they started making switches, and so on.

And if we return to what is happening with graphene, hundreds of companies are already making profit from this in China. This is the data that I know. Products using graphene can be seen everywhere: they make soles for shoes, paint with all kinds of fillers for protection, and much more. It's slow, but it's picking up. Although it is slow on the scale of the industry. Since 2010, they learned how to make graphene in masses, and not like us - under a microscope. So give it time. In ten years, you will probably see not only skis and tennis rackets that are called graphene, but something truly revolutionary and unique.

How is work going on in your research group now?

The style of work is not to be confined to one and the same direction, as I usually say, from the scientific cradle to the scientific grave. In the Soviet Union, at least, it was very popular: people defend their candidate’s, doctor’s and do the same thing until retirement. Of course, in any business you need professionalism, but at the same time, you need to look at what is on the side. I try to switch from one direction to another: we have such conditions, but what else can be done in this area?

What I was talking about is this “two-dimensional nothingness” - this idea came from a completely different area. For some reasons that only later became clear, it turned out to be quite interesting. new system. Therefore, you need to jump like a frog from one area to another, even if there is no knowledge, but there is a background. You can jump into a new area and see from your perspective what you can do there. And this is very important. This is especially good with students who approach new topics with great enthusiasm.

There are many young scientists in your group today, including from Russia. In your opinion, what motivates students today—both in Russia and abroad—to engage in science, including fundamental science? After all, even now the prospects in the same industry are more obvious.

People try their hand. Five to six million people in the world are engaged in science: some try it, some don’t like it. Life in science, especially fundamental science, is not sweet. When you are a graduate student, you feel like you are doing science. And when you get a permanent job, there’s a lot of studying involved, and you have to write grants, and submit articles for magazines, and it’s a hassle. Therefore, compared to industry, where everything is a little like in the army, in science it is different.

It is possible to survive, but you need to run very quickly: this is not a hundred meters, this is a marathon for life. And you also need to study all your life. Some people like it like I do. So much adrenaline every time! For example, when you open a referee report for your article. And being a Nobel laureate doesn't help. It works something like this: “Ah, Nobel laureate? Let’s teach him how to really do science.” Therefore, in the evening, when it’s time to go to bed, I never open reviewers’ comments.

There is enough adrenaline, everything is interesting, you learn something new all your life, so some young people, cut from the same cloth, want to make their way in science. The only thing, based on my experience, the truly successful scientists who have passed through me are those who started as PhD students. If they come as postdocs, then it is already quite late to retrain, there is already pressure: they need to publish, find grants. But at the PhD level, you can still think about the soul. During this time in graduate school, they develop a work style: if they like it, they become quite successful.

Just touching on the topic of grants. Many scientists say that working in science involves quite a lot of routine, bureaucracy, and you constantly need to look for funding. When should the research itself be carried out?

Taxpayers provide money for science from their hard earned money. And what research to fund is decided by peers, who are other scientists. Therefore, we need to prove to them, get used to high competition. Even if they give a lot of money, it still won’t be enough for everyone, so this is somehow an inevitable part of science: you need to write applications for grants, publish good articles. If the article is good, it will be referenced. People vote with their feet, or in this case with their pen, on which article to write. The number of links shows how successful you are and how much your colleagues respect your results. Competition in science is as intense as in sports at the Olympic Games.

In Europe this is not so pronounced, but in America full professors in my position spend almost all of their time writing grants and talking to their students once a month. Most of my time is spent writing articles for my undergraduate and graduate students. Because when good results presented poorly - the heart bleeds. Is it better than writing grants, or worse? Don't know.

Of course, the work needs to be well presented to the scientific community, but, on the other hand, the results scientific research it is necessary to communicate this to a wide range of people—the same taxpayers. Here I would like to touch on the topic of popularizing science: to what extent, in your opinion, do scientists themselves need to tell a large audience about their work?

Where to go? If taxpayers don’t understand, then the government stops understanding. People still respect science, especially educated people. If this had not happened, all the money would have been given, as they say, for immediate needs - spent on bread and butter. And it would be like in Africa, where nothing is spent on science. As we know, this is a spiral that ultimately leads to the collapse of the economy. Therefore, I have great respect for people who know how and love to present the results of scientific research.

Among the professors I know, many frown upon those who appear on television and the like. For example, in our department he works ( English physicist, works in particle physics, research fellow at the Royal Society of London, professor at the University of Manchester and a famous popularizer of science - editor's note). Even many people are skeptical about him: they say, he’s not a real professor, he hasn’t done anything in science. The fact that he knows how to present research results is very important, someone should do this.

Andrei Geim at the Nobel Prize in Physics ceremony. Stockholm, 2010

Born in 1958 in Sochi, in a family of engineers of German origin with Jewish roots on his mother’s side. In 1964, the family moved to Nalchik.

Father, Konstantin Alekseevich Geim (1910-1998), since 1964 worked as chief engineer of the Nalchik Electric Vacuum Plant; mother, Nina Nikolaevna Bayer (born 1927), worked as chief technologist there.

In 1975, Andrei Geim graduated with a gold medal high school No. 3 of the city of Nalchik and tried to enter MEPhI, but was unsuccessful (the obstacle was the applicant’s German origin). After working for 8 months at the Nalchik Electrovacuum Plant, in 1976 he entered the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology.

Until 1982, he studied at the Faculty of General and Applied Physics, graduated with honors (“B” in his diploma only in the political economy of socialism) and entered graduate school. In 1987 he received a Candidate of Sciences in Physics and Mathematics from the Institute of Physics solid RAS. He worked as a research fellow at the Institute of Physics and Technology of the USSR Academy of Sciences and at the Institute for Problems of Microelectronics Technology of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

In 1990 he received a fellowship from the Royal Society of England and left Soviet Union. He worked at the University of Nottingham and also briefly at the University of Copenhagen before becoming an Associate Professor and, from 2001, at the University of Manchester. Currently Head of the Manchester Center for Mesoscience and Nanotechnology and Head of the Condensed Matter Physics Department.

Honorary doctorate from the Technical University of Delft, ETH Zurich and the University of Antwerp. He holds the title of Langworthy Professor at the University of Manchester (Earnest Rutherford, Lawrence Bragg and Patrick Blackett were among those awarded this title).

In 2008, he received an offer to head the Max Planck Institute in Germany, but refused.

Subject of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. His wife, Irina Grigorieva (a graduate of the Moscow Institute of Steel and Alloys), worked, like Geim, at the Institute of Physics and Technology of the USSR Academy of Sciences, and currently works with her husband in the laboratory of the University of Manchester.

After Geim was awarded the Nobel Prize, the intention was announced to invite him to work at Skolkovo. Game said: At the same time, Game said that he does not have Russian citizenship and feels comfortable in the UK, expressing skepticism about the project Russian government create an analogue of Silicon Valley in the country.

Among Geim's achievements is the creation of a biomimetic adhesive (glue), which later became known as gecko tape.

Also widely known is the experiment with, among other things, the famous “flying frog”, for which Game, together with the famous mathematician and theorist Sir Michael Berry, received the Ig Nobel Prize in 2000.

In 2004, Andrei Geim, together with his student Konstantin Novoselov, invented the technology for producing graphene, a new material that is a monatomic layer of carbon. As it turned out during further experiments, graphene has a number of unique properties: it has increased strength, conducts electricity as well as copper, surpasses all known materials in thermal conductivity, is transparent to light, but at the same time dense enough to not allow even helium molecules to pass through - the smallest known molecules. All this makes it a promising material for a number of applications, such as creating touch screens, light panels and, possibly, solar panels.

For this discovery (Great Britain) awarded Game in 2007. He also received the prestigious EuroPhysics Prize (together with Konstantin Novoselov). In 2010, the invention of graphene was also celebrated Nobel Prize in physics, which Geim also shared with Novoselov.

- Andrey Geim is interested in mountain tourism. His first “five-thousander” was Elbrus, and his favorite mountain was Kilimanjaro

- The scientist has a peculiar sense of humor. One confirmation of this is an article on diamagnetic levitation, in which Geim’s co-author was his favorite hamster (“hamster”) Tisch. Game himself stated on this occasion that the hamster’s contribution to the levitation experiment was more direct. This work was subsequently used in obtaining a Ph.D.