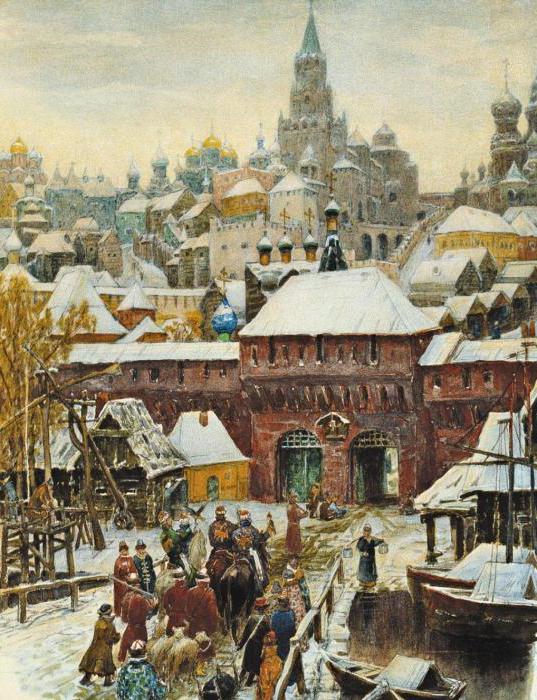

George Kennan - World War II diplomacy through the eyes of the American ambassador to the USSR, George Kennan. Anglo-French diplomacy and Nazi Germany on the eve of World War II

The Soviet Union entered World War II two and a half weeks after it began. On September 17, 1939, the Red Army crossed the Polish border. It struck from the east on the Polish army, desperately defending itself from the German invasion. Poland was defeated by the joint efforts of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. This was openly and loudly declared by the People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs V.M. Molotov at the session of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on October 31, 1939.

In a fairly short period between the campaign in Poland and the German attack on the USSR, three stages of Soviet foreign policy can be tentatively outlined: the first - from September 1939 until the defeat of France in June 1940, the second - until the Soviet-German talks in Berlin in November 1940, the third - before the German attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

At the first stage, Stalin, using two agreements with Nazi Germany, tried to quickly realize the opportunities that were opened by secret agreements.

After the Red Army occupied Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, that is, Eastern Poland, preparations began for the "free will" of the twelve million people who lived there in favor of unification with the Ukrainian and Byelorussian SSR. But even earlier, special units of the NKVD arrived in the territory just occupied by the Red Army. They began to identify "class alien" elements, arrested and deported them to the east of the country. On October 31, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted laws on the "reunification" of these areas with the Byelorussian and Ukrainian SSRs, respectively.

Curious documents have been preserved in the archive - the texts of declarations of the National Assembly of Western Belarus on the confiscation of landlords' lands, on the nationalization of banks and large-scale industry, on the nature of the power created in Western Belarus with additions and corrections made by the secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b) Zhdanov personally. So to speak, volition is volition, and there is no need to cry ...

Stalin's plan to absorb the Baltic countries

As I have already mentioned, the three Baltic republics - Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia - also fell into the sphere of state interests of the USSR. In the fall of 1939, just at the moment when the Treaty of Friendship and Border was signed by Molotov and Ribbentrop in Moscow, the USSR forced the Baltic countries to sign mutual assistance pacts and allow the entry of "limited contingents" of Soviet troops into their territory.

The Baltic plans of Stalin were agreed with Hitler through Ambassador Schulenburg and Ribbentrop himself. As in the case of Eastern Poland, the Soviet scenario was the same - in October 1939, i.e. when the Baltic republics were still independent, although they were forced to accept Soviet garrisons, the NKVD (General I. Serov) issued an order to prepare for the deportation of hostile elements. This means that the plan for the absorption of the Baltic was already developed then.

The schedule of "free will" of Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians was prepared in Moscow. In strict accordance with the established schedule, people's governments were created in these countries; then on June 17-21, 1940 elections were held in the People’s Sejm of Lithuania and Latvia, on July 14-15 in the State Duma of Estonia. On July 21, 1940, on the same day, Soviet power was proclaimed in all the Baltic countries, and three weeks later all three were adopted by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR into the Soviet Union. Immediately began practical preparations for the mass deportation of part of the indigenous population.

It was the turn of Bessarabia. On June 26, Molotov demanded that Romania immediately return Bessarabia, annexed to Romania in 1918. In August, Bessarabia was already merged with the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, which was part of the Ukrainian SSR, and thus the Moldavian Union Republic was created. At the same time, Northern Bukovina was “seized”, to which there were no historical rights, since it was part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. This act was not provided for by the German-Soviet secret protocol. The Germans naturally frowned. Molotov explained to the German ambassador Schulenburg that Bukovina "is the last missing part of a united Ukraine."

The occupation of the Baltic states, Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina was, of course, associated with the defeat of France and the German occupation of the territories of several European states in the north and north-west of Europe. The victories of the German partner in the West had to be balanced.

Stalin was now afraid of a speedy conclusion of peace in the West, while the USSR had not yet implemented a program of territorial expansion.

The Munich agreement of September 30, 1938 and the surrender of Czechoslovakia to German demands under pressure from England and France gave Stalin hope that the Soviet Union should not be put off the shelf of the realization of its own plans for a geopolitical and strategic order.

Just a few days before the opening of the XVIII Congress of the CPSU (b) of Finland, it was proposed to lease to the Soviet Union part of the Finnish territory, namely the island of Sursari (Hogland) and three others, on which the USSR intended to build its military bases. The proposal was made by Litvinov two months before his own resignation from the post of People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs. Freedom-loving Finns, of course, rejected this proposal, even despite the proposal to receive in exchange a much larger territory of Soviet Karelia. Let us note that Litvinov, whose name is invariably associated with a collective security policy, did not see anything shameful in convincing an independent state to cede its territory. For Finland, however, these were not “barren islands", but part of their native land.

Preparation of the USSR for the war with Finland 1939

In the summer of 1939, that is, already during the ongoing negotiations with Great Britain and France on mutual assistance in the event of German aggression, the Main Military Council of the Red Army considered a plan of military operations prepared by the General Staff against Finland. He was reported by the Chief of the General Staff Shaposhnikov. Although the possibility of direct support for Finland from Germany, Britain, France, and the Scandinavian states was recognized, it was not for this reason that the plan was rejected by Stalin, but because of the reassessment of the difficulties of the war by the General Staff. The new plan was developed by the commander of the Leningrad Military District, K.A., who had just been released from prison. Meretskov. The plan was designed for an initial strike and defeat of the Finnish army within two to three weeks. It was a kind of Soviet blitzkrieg plan. It was based on the factor of surprise and arrogant neglect of the enemy’s potential capabilities, similar to what it was in the German calculations of the war against the USSR.

While a plan of war against Finland was being developed (it lasted five months), the Soviet Union exerted continuous diplomatic pressure on Finland, putting forward more and more demands, each of which meant not only transferring to the Soviet Union in the form of exchange part of Finnish territory, not only the leasing of another part of the territory for the construction of Soviet military bases there, but also the disarmament of the Finnish defensive strip on the Karelian Isthmus ("Mannerheim Line"), which completely transferred the fate of Finland to hands of the mighty southern neighbor. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union covered up preparations for war with these diplomatic maneuvers, or, as the current chief of the General Staff now writes, Army General M. Moiseyev, "final military preparations were hastily carried out." Soviet historian Viktor Kholodkovsky, without a doubt, the country's most competent expert on the history and politics of Finland and Soviet-Finnish relations, quotes Kekkonen in one of his recent articles, at that time the minister in the Kayander government who rejected the Soviet demands: “We knew that the cession of the required territory would mean a mortal gap in the country's defense system. And we could assume that it would mean such a gap if we had a neighbor like Russia. "

In the USSR began psychological preparation for the war against Finland. The tone was set by the People's Commissar of Foreign Affairs V.M. Molotov, who delivered a long speech at the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on October 31, 1939. In it, he acknowledged, among other things, that Finland was invited to disarm its fortified areas, which, according to Molotov, was in line with the interests of Finland. For some reason, the Finns themselves did not think so. What prompted the Soviet leadership to pursue such a stubborn policy of pressure on the small Finnish people? Confidence in the law of power, its extraordinary; and most importantly - it was safe, since Finland, by agreement with Nazi Germany, had moved into the sphere of Soviet interests, just like the Baltic states, and England and France were absorbed in their own military concerns. By this time, the three Baltic states had already been forced by the Soviet Union to sign mutual assistance agreements with him and allowed to place on their territory a "limited contingent" of Soviet armed forces, which very soon turned into unlimited economic management in the territory of the sovereign Baltic republics.

Finland, of course, did not want war and would prefer to resolve the complications arising through the fault of the Soviet Union peacefully, but Stalin sought to unconditionally accept his demands. The Finnish intimidation company ran parallel to military preparations. Pravda published articles unprecedentedly rude to Finland. Their tone could only be compared with the tone of Soviet newspapers during the Moscow trials of the second half of the 30s.

On October 5, the following Soviet demands were transferred to Finland: the exchange of the territory of the Karelian Isthmus, owned by the Finns, for a twice as large, but sparsely populated and undeveloped part of the territory of Soviet Karelia; the right to lease the Hanko Peninsula, located at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, and the non-freezing port of Petsamo on the Rybachy Peninsula for the construction of Soviet naval and air bases there. For Finland, the adoption of Soviet conditions would mean the loss of any opportunity to protect themselves. Offers were declined. In the face of the impending military threat from the USSR, Finland was forced to take the necessary defensive measures. Even now, in 1990, the Soviet military department is trying to lay equal responsibility for the outbreak of war on both sides.

“The Finnish side,” says the comment of the USSR Ministry of Defense quoted above, “not only didn’t show readiness to reach any mutually acceptable agreements with the USSR, but ...” etc. or "Having not exhausted all the possibilities of a political settlement, the USSR and Finland have practically taken a course towards solving the problems by military means." That is, the aggressor and his victim are put on the same board. On November 3, 1939, Pravda threateningly stated in an editorial: “We will hell the game of political gamblers and go our own way, no matter what. We will ensure the security of the USSR without looking at anything, breaking all and all kinds of obstacles in the way to the goal".

Four Soviet armies, meanwhile, were deployed on the Karelian Isthmus, in East Karelia and the Arctic. Finally, on November 26, the Soviet government announced the shelling of Soviet territory in the area of \u200b\u200bthe village of Mainila, 800 meters from the Finnish border; there were casualties among the Soviet military. The USSR accused the Finns of provocation and demanded the withdrawal of Finnish troops at a distance of 25-30 km from the border, i.e. from her line of defense on the Karelian Isthmus. Finland, for its part, proposed a mutual withdrawal of troops and an investigation at the scene in accordance with the 1928 Convention. According to Khrushchev’s testimony, Stalin had no doubt that the Finns were scared and surrendered after the USSR unilaterally broke the non-aggression pact on November 28. Finland was accused of holding Leningrad at risk. November 30, Soviet troops opened hostilities. Little people were not afraid. The war has begun.

Lessons from the war against Finland for the USSR

It turned out that, despite the five-month preparations, the Red Army is not ready for war. Inability to act in winter conditions revealed immediately. Neither Komsomol volunteers abandoned from Moscow and Leningrad, nor mobilized skiers-athletes, many of whom died senselessly and ingloriously, did not help. Attempts to overturn the Finnish army with frontal strikes on the fortifications of the Mannerheim line turned into bloody losses. “Our troops,” the Ministry of Defense said in a comment, “failed to accomplish the assigned task in any of the areas, primarily on the Karelian Isthmus.”

Everything refused: tanks frozen in frost; roads clogged with vehicles; there were not enough mortars and small arms, there was no winter clothes. They found the guilty one right away: Meretskov was replaced by Marshal Tymoshenko, and Army General Stern was called from the Far East. Only after significant forces of all arms were transferred to the Finnish front, on February 11, 1940, a new offensive began, the struggle went on for meters. A month later, the Finnish defensive line was broken, and Finland was forced to accept the conditions imposed on her by the winner. The peace treaty, signed in Moscow on March 12, 1940, transferred the Karelian Isthmus to the Soviet Union, including Vippuri (Vyborg) and Vyborg Bay with islands, the western and northern shores of Lake Ladoga with the cities of Kexholm, Sortavala, Suoyarvi, a number of islands in the Gulf of Finland, and a number of others territories on the Sredny and Rybachy peninsulas, as well as for rent the Hanko Peninsula, with the right to maintain here, in addition to naval and air bases, also ground garrisons.

The principle of ideological warfare, used during the civil war, was applied in the preparation and during the war against Finland. A puppet government was prepared for her, led by one of the leaders of the Comintern, the former head of the Communist Party of Finland O.V. Kuusinenom. The plan provided for the creation of the Karelian-Finnish Union Republic subsequently by combining the Karelian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic with Finland.

However, Kuusinen himself did not play any independent role in this political farce. A.A. Zhdanov - the first secretary of the Leningrad Regional Party Committee, he is also a member of the Military Council of the 7th army, he is also a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU (b), was a key figure here.

Archival documents have brought us curious evidence of how the Finnish Democratic Republic was created, with whose government the USSR immediately signed an agreement on mutual assistance and friendship.

The first document - a message about the formation of the FDR government and the declaration of the "People’s Government" - was written by Zhdanov. Considering, apparently, his form for publication, Zhdanov made notes: “radio interception” and “translation from Finnish” (!). The educated man was the Leningrad secretary ... This six-page document announced the liberation of the Finns from the power and oppression of the "bourgeoisie, its minions"; in short, the document contained a complete set of derogatory epithets against the “ruling clique” and a promise to the Finns freedom from exploitation. The second document, written by Zhdanov, is a draft instruction on how to begin political and organizational work in areas of Finland "liberated from white power."

The third document (eleven-page) - an appeal to the working people of Finland - was also written personally by Zhdanov. The funny thing is, however, if it is only appropriate to use this word here, the text of the oath of a soldier of the People's Army of Finland. Zhdanov took the printed text of the military oath of servicemen of the Red Army as a basis and introduced several purely formal amendments there.

This inglorious war cost the Soviet people considerable sacrifices. According to the information contained in the certificate-commentary of the Ministry of Defense of the USSR, the losses of the Red Army alone killed more than 67 thousand people. The Finnish army lost over 23 thousand people. These data are seriously different from those given by various researchers. V.M. Kholodkovsky believes, relying on sources, that Soviet losses amounted to about 74 thousand killed and 17 thousand missing, and only 290 thousand. Finnish losses were 3-4 times less. B.V. Sokolov agrees with the Finnish assessment: the Soviet losses of the dead amounted to approximately 200 thousand and cites its own calculations on this score.

The negative consequences of the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939

The moral damage caused by the war against Finland was colossal. In December 1939, the League of Nations formally condemned the USSR as an aggressor and expelled him from the League of Nations. Only three states were branded as aggressors - Japan, Italy and Germany. Now the USSR was added to this list. One of the reasons that prompted the USSR to conclude a peace treaty with Finland as soon as possible and not try to completely seize this country was that there was a real danger of moving the center of the war from the Western Front to North-Eastern Europe. The Western Allies began to seriously think about sending a 50,000th volunteer corps to help Finland. However, the Finnish government did not want to turn the territory of their country into a force field of the great powers, as happened with Spain in 1936-1939.

Another negative result for the USSR, more important than its expulsion from the League of Nations, was Germany’s growing confidence that the USSR was militarily weaker than it seemed before. This strengthened the position of supporters of the war against the USSR.

“In our war against the Finns,” Khrushchev said, “... we could ultimately win only after enormous difficulties and incredible losses. Victory at this cost was actually a moral defeat.”

The borders of the USSR were advanced west. However, there was very little time left to strengthen them. This should have become apparent after the signing of the Tripartite Pact by Germany, Japan and Italy on September 27, 1940.

Although the Soviet government was informed by Germany of the impending conclusion of the Tripartite Pact before its publication, it was not misled about the true nature of the pact. The editorial of the newspaper Pravda of September 30, 1940 regarding the Tripartite Pact emphasized that its signing means "further aggravation of the war and the expansion of its scope." At the same time, the Soviet press drew attention to the reservation that the Tripartite Pact did not affect the relations of its participants with the USSR, and clarified that this reservation should be understood “as a confirmation of the strength and significance of the non-aggression pact between the USSR and Germany and the non-aggression pact between the USSR and Italy. "

The fact that the USSR did not doubt the meaning of the Triple Pact as a pact on the preliminary division of the world was also evidenced by the more friendly tone of the Soviet press towards England. For example, on October 5, 1940, Pravda posted a very detailed and sympathetic correspondence from London about a TASS correspondent visiting one of the London field batteries of anti-aircraft guns. From this article, the reader could easily conclude that England is fighting seriously and its strength is growing. There were many other events that made Stalin think about the near future. It seemed very gloomy. Germany was clearly targeting the Balkans.

In these months, only one event will truly delight Stalin. On August 20, 1940, the NKVD finally completed the hunt for L.D. Trotsky. He is mortally wounded by an ice ax blow. Pravda publishes an editorial entitled The Death of an International Spy, and Izvestia, even worse, an article by D. Zaslavsky, “A Dog — Dog Death.”

But the assassination of Trotsky cannot change anything in a terrible situation, just as her articles in the Soviet press cannot change the "aggressor of Great Britain and the United States of America helping the military efforts of it." The Soviet Union continues to maintain diplomatic relations with both states, but Stalin rejected British attempts to enter into closer relations with the USSR. Although the tone of the Soviet press is softening, and the stupid campaign against joining the United States war has completely stopped, Stalin continues to focus on Germany, despite the tensions that arise between the USSR and the Reich (Vienna arbitration, the problem of neutrality of Sweden, the sending of German troops to Romania, etc. ) Relations between the two states are starting to deteriorate.

Possible agreement on the division of the world between the USSR and Germany

By the end of 1940, under the fifth of Germany, there was an area of \u200b\u200b4 million square meters. km with a population of 333 million people. In the summer of 1940, the systematic use of the European economy for the needs of the war began. Thus a significant number of Germans were freed up for military service. The development of an attack plan on the USSR goes on as usual, but in the meantime Ribbentrop invites Molotov to arrive in Berlin. There Molotov met with Hitler. On November 12, 1940, Molotov, accompanied by a large group of experts, arrives in Berlin. The official German record of his talks with Hitler says: “Molotov expressed his agreement with the statements of the Führer on the role of America and England. The participation of the USSR in the tripartite pact seems completely acceptable to him in principle (emphasized by me. - A. N.), bearing in mind "Russia should cooperate as a partner, and not just as an object. In this case, he does not see the difficulties of the Soviet Union participating in the common effort." At the same time, Molotov needs clarification, in particular about the "great Asian space", puts forward a number of demands regarding Finland and Southern Bukovina, Bulgaria and the Straits. Before leaving for Moscow, Molotov is presented with projects on dividing the world into spheres of influence between Germany, Italy, Japan and the USSR. On November 14, Molotov returned to Moscow.

In the Soviet Union, a version has been established for 50 years (and it is present in all, without exception, historical studies, official stories, memoirs published before 1989) that the USSR rejected Hitler's offer to participate in the division of the world. Nothing of the kind happened. On November 26, a reply was sent to Hitler in which the Soviet government agreed with the German draft world division, but with some amendments: the Soviet sphere of influence should have spread to areas south of Baku and Batum, i.e. include eastern Turkey, northern Iran and Iraq. The Soviet Union also demanded consent for the construction of its naval base in the Straits. In addition, Soviet demands related to the role of Turkey, the withdrawal of German troops from Finland, the elimination of Japanese concessions in Northern Sakhalin, the inclusion of Bulgaria in the Soviet orbit.

Later, Molotov several times asked the Germans for a response to Soviet counter-proposals, but the German government did not return to this problem. Thus, if the agreement on the division of the world did not take place, then that was not the merit of the Soviet government.

Soviet-Bulgarian relations before the Second World War

Since the end of 1939, there has been a slight improvement in Bulgarian-Soviet relations. Economic and cultural agreements were concluded that contributed to the establishment of closer ties between the USSR and Bulgaria. The traditional sympathies of the Bulgarian people for the Russian people, which helped in their past struggle against Turkish rule, the widespread idea of \u200b\u200bSlavic solidarity were cemented by the great interest of the Bulgarians in Russia and the socialist traditions of the Bulgarian labor movement. In addition, the significant strengthening of Germany in the Balkans as a result of its victory in the West caused considerable excitement in Bulgaria. The fears of the attack from Turkey also played a role. The Soviet Union was the only country that could really resist German intrigues in the Balkans. During the Soviet-Bulgarian negotiations in the autumn of 1939, the Soviet government proposed to sign an agreement on friendship and mutual assistance. However, the Bulgarian government rejected this offer. Subsequently, under the influence of events in Western Europe and the fear of increased Soviet influence, the Bulgarian government was increasingly inclined towards a block of fascist aggressors.

After the November talks in Berlin, the Soviet government on November 19, 1940 turned to Bulgaria with a proposal to conclude an agreement on friendship and mutual assistance. A week later, General Secretary of the People's Commissariat A. A. Sobolev arrived in Sofia, confirming this proposal. The Soviet Union declared its readiness to render assistance to Bulgaria, including military assistance, in the event of an attack by a third power or a group of powers. The USSR expressed its readiness to provide Bulgaria with financial and economic assistance. At the same time, the Soviet Union stated that the pact would in no way affect the existing regime, independence and sovereignty of Bulgaria. However, it was no longer a secret that the Soviet Union was aiming south. The Soviet attack on Finland served as a warning. On the same day, November 25, the Soviet proposal was discussed at a narrow meeting of the Bulgarian Cabinet of Ministers with Tsar Boris and rejected. The German envoy to Sofia was informed of this Soviet proposal.

Although the Bulgarian government rejected the Soviet proposal, it played a well-known positive role, slowing down the transition of Bulgaria to the camp of fascist aggressors. The Bulgarian envoy in Stockholm reported to his government in mid-December 1940: "Here, the recent Russian intercession in favor of Bulgaria and Sweden is noted with interest in order to preserve these two countries not only outside the war, but also outside the combination of Germany against England "

In January 1941, in connection with the widespread reports that German troops were being transferred to Bulgaria with the consent of the USSR, the Soviet government officially declared that if such a fact did occur, then "this happened and is happening without the knowledge and consent of the USSR."

Four days later, the Soviet government declared to the German ambassador in Moscow, Schulenburg, that it considers the territory of the eastern part of the Balkans as a security zone of the USSR and cannot remain indifferent to events threatening this security. The same was repeated on January 17, 1941 by the Soviet Plenipotentiary in Berlin to the State Secretary of the German Foreign Ministry Weizsacker. However, on March 1, the Bulgarian government sided with the Triple Pact, providing its territory for the passage of German troops for military operations against Greece, and then against Yugoslavia.

The Soviet government, in a special statement, condemned this step of the Bulgarian government, while indicating that its position "does not lead to peace, but to the expansion of the sphere of war and the pulling of Bulgaria into it." On March 3, the German ambassador in Moscow was told that Germany could not count on the Soviet Union's support for its actions in Bulgaria.

Failure with Bulgaria showed that Germany had already begun hostile military-political steps against the USSR. The clash in Bulgaria was actually a test of the strength of Soviet-German relations. From the results of this test it was necessary to draw appropriate conclusions.

Germany disguises preparations for an attack on the USSR

Serious fears arose in the Soviet Union due to Turkey’s position during the “strange war”, and also due to the fact that the Turkish government continued to maneuver between the belligerents, tending to one or the other, depending on the emerging balance of forces in each this moment. However, the entry of German troops into Bulgaria scared the Turkish government. As a result of the exchange of views between the Soviet and Turkish governments in March 1941, mutual assurances were given that in the event of an attack on one of the parties, the other could "count on full understanding and neutrality ..."

Events in the Balkans have shown that relations between Germany and the USSR are developing in a menacing direction. The German-Soviet contradictions, which were irreconcilable as a result of the Nazi aspiration for world domination and only mitigated by the agreements of 1939, now made themselves felt with renewed vigor. Germany continued to prepare bridgeheads near the borders of the USSR. Faced with the negative position of the Soviet Union regarding German politics in the Balkans, the Nazis tried to scare the Soviet Union with their military power. On February 22, 1941, a senior Foreign Ministry official, Ambassador Richter, on behalf of his superiors in a strictly secret coded telegram to the ambassador in Moscow, Schulenburg, announced that the time had come to announce the number of German troops in Romania in order to impress Soviet circles . The 680,000th German army is on full alert. It is well technically equipped and has in its composition motorized parts. This army is supported by "inexhaustible reserves." Ritter invited all members of the German missions, as well as through proxies, to begin disseminating information about German assistance. This help must be filed in an impressive manner, Ritter wrote, emphasizing that it is more than enough to meet any eventuality in the Balkans, no matter where it comes from. It was proposed to disseminate this information not only in government circles, but also among interested foreign missions accredited in Moscow.

Along with intimidation, the Nazis tried to mask the ongoing military preparations along the Soviet-German border. January 10, 1941 between Germany and the Soviet Union, an agreement was signed on the Soviet-German border of the river. Igorka to the Baltic Sea. After the conclusion of the contract by the authorized representatives of both parties, the demarcation of the border defined by the contract should have been carried out. Negotiations on the commission’s work began on February 17. The German side dragged them in every way. At the request of the high command of the ground forces, Schulenburg was instructed to delay negotiations in every possible way to prevent the work of the Soviet commission on the border. The Germans feared that otherwise their military preparations would be revealed.

The Nazis intensified aerial reconnaissance of the Soviet border regions. At the same time, with the aim of disguising themselves, they began to claim that rumors about the impending German attack on the Soviet Union were specially spread by the "English arsonists". Just at that time, the Soviet Union received warnings through diplomatic channels about German plans for an attack on the USSR.

A new complication of relations between the USSR and Germany then occurred due to Yugoslavia. On March 27, 1941, the government of Tsvetkovich was overthrown in Yugoslavia and signed an agreement on accession to the Tripartite Pact. The Yugoslav people were determined to offer armed resistance to the German aggressor. “Recent events in Yugoslavia,” Pravda wrote, “have clearly shown that the peoples of Yugoslavia are striving for peace and do not want war and drawing the country into the maelstrom of war. Through numerous demonstrations and rallies, broad sections of the population of Yugoslavia have protested against foreign policy Tsvetkovich’s government, which threatened Yugoslavia with drawing her into the orbit of war ... " On April 5, a treaty of friendship and non-aggression was signed between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, according to which, in the event of an attack on one of the parties, the other pledged to comply with a "policy of friendly relations with it." This formula was vague and non-binding. On the day the treaty was published on April 6, Hitlerite Germany attacked Yugoslavia. The Soviet Union publicly condemned this act of aggression in a message from the People’s Commissariat of April 13, 1941 on the attitude of the USSR government to Hungary’s attack on Yugoslavia. Although Hungary was condemned in the statement, Hitler Germany, the initiator of the aggression, was also condemned. Events associated with Yugoslavia showed that relations between Germany and the USSR were approaching a denouement.

Improving relations between the USSR and Japan before World War II

Amid growing tension, the Soviet Union was able to achieve major success in dealing with another potential adversary - Japan.

Already from the end of 1939, the prospect of at least a temporary improvement in Soviet-Japanese relations gradually began to emerge. After Khalkhin Gol, some sobering began in Japanese military circles. Attempts to exert pressure on the Soviet Union by military means ended in failure. The war against the USSR seemed extremely difficult and dangerous. The conclusion of the Soviet-German non-aggression pact of August 23, 1939, which caused a cooling in relations between Axis partners, also had a certain influence on Japanese policy. In the ruling circles of Japan, they were aware that under these conditions, Japan's chances of waging a victorious war against the USSR significantly decreased. Despite the anti-Soviet campaign launched in Japan during the Soviet-Finnish conflict, things did not go further than anti-Soviet statements in the press. A number of Japanese industrialists and financiers interested in developing economic relations with the USSR, and especially the fishing industry, pressured the government, demanding better relations with the USSR and the signing of a new fishing convention, as the previous one expired in 1939. Articles appeared in the Japanese press that insisted at the conclusion of a non-aggression pact with the USSR.

This was the situation at the time of the collapse of France. This event significantly strengthened those Japanese circles who advocated expansion towards the southern seas. They found support also from Germany, which at that time considered war against England its main task and therefore advocated the settlement of Soviet-Japanese relations "in order to untie Tokyo's hands for expansion to the south. This was to attract the attention of England and the United States to The Pacific, weakening their position in Europe. "

In early June, the issue of the border line between Manzhou-Guo and the Mongolian People's Republic was settled in the conflict area of \u200b\u200b1939. A month later, the Japanese ambassador in Moscow Togo proposed to conclude a 5-year Soviet-Japanese treaty. The essence of such a treaty, which would be based on the Soviet-Japanese treaty of 1925, was to maintain neutrality in the event that one of the parties was attacked by a third party. The Soviet Union agreed to the Japanese proposal, but stipulated its rejection of the 1925 treaty as "the basis of the new agreement, since the 1925 convention was largely outdated. In connection with the change of cabinet in Japan in July 1940, negotiations were interrupted. and Togo’s ambassador was recalled to Tokyo, however, the trend towards a settlement of relations with the USSR continued to intensify as favorable prospects emerged to strengthen Japanese aggression in Southeast Asia as a result of the weakening of England and the defeat of France and Holland. The sentence was briefly formulated at the end of September 1940 by the Japanese Hopi newspaper: “If Japan wants to advance in the south, it should be free from fears in the north.” A new ambassador, Taketawa, who, according to the Foreign Minister, was appointed to Moscow Matsuoka was instructed to "open a new page in relations between Japan and the Soviet Union."

The conclusion of the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940 meant, in those specific conditions, the strengthening of Japanese circles advocating southward aggression, i.e. against English possessions in Asia. At the same time, it was necessary to reckon with the fact that in the event of a change in the international situation, for example, in the event of a German attack on the Soviet Union, Japan could support it. This point has been repeatedly emphasized by the responsible leaders of the Japanese government in secret meetings.

In the fall of 1940 and in early 1941, the Soviet-Japanese negotiations were continued. The USSR put forward a proposal to sign an agreement on neutrality, subject to the liquidation of Japanese oil and coal concessions in Northern Sakhalin. In this case, the USSR was obliged to compensate the concessionaires and supply Japan with Sakhalin oil for 5 years under ordinary commercial conditions. The Japanese government agreed to discuss the draft treaty, but rejected the proposal to eliminate concessions.

However, despite all the difficulties, Soviet-Japanese relations were already entering a period of temporary settlement. Its prospects improved after the signing in the second half of January 1941 of a protocol on the extension of the fishing convention until the end of 1941. A certain impact was exerted on the position of Japan and the unsuccessful start of Japanese-American negotiations.

Soon after the signing of the Tripartite Pact, the Japanese government turned to the Soviet government with a proposal to conclude a non-aggression pact. At the same time, Japan asked Germany to promote a pact.

The plan proposed by Ribbentrop was rejected in November 1940 by the Soviet government. Meanwhile, supporters of the direction of Japanese aggression to the south exerted an increasing influence on Japanese foreign policy and demanded to ensure the security of the Japanese rear in the north, i.e. in the northeastern regions of China, bordering the Soviet Union and the Mongolian People's Republic. A significant role was played by the fact that the lessons of Khalkhin-Gol had not yet been forgotten by the Japanese military. The prospect of a war against the USSR seemed far more dangerous than an attack on British possessions in Southeast Asia, given the fact that England was in a very difficult situation. On February 3, 1941, at a joint meeting of the government and representatives of military circles, the "Principles for Negotiating with Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union" were approved. On March 12, Japanese Foreign Minister Matsuoka left for Europe. During a stop in Moscow, Matsuoka invited the Soviet government to conclude a non-aggression pact. Recall that in the 30s the Soviet Union repeatedly turned to Japan with such a proposal, but then it was rejected by Japan. In the new situation, the Soviet Union did not consider it sufficient to conclude only a nonaggression pact. It was important to secure Japan's neutrality in case of complications with Germany. Therefore, the Soviet Union put forward a counter-proposal: conclude an agreement on neutrality. March 26 with this proposal, Matsuoka and went to Berlin.

German pressure on Japan to induce a pro-German position

After the publication of the Barbarossa directive, Hitlerite Germany began to put pressure on Japan to force her to take a position that would be favorable to German plans. In the second half of January 1941, when meeting with Mussolini at Berghof, Hitler spoke of Japan, "whose freedom of action is limited by Russia, just like Germany, which should keep 80 divisions on the Soviet border in constant readiness in case of actions against Russia." Assessing Japan as an important factor in the struggle against England and the United States, Hitler, not without intent, emphasized that part of the Japanese forces was constrained by the Soviet Union.

Hitler, receiving the Japanese Ambassador Kurusu on February 3, 1941, who paid a farewell visit to him, made the ambassador transparent hints about the possible development of German-Soviet relations. “Our common enemies,” he said, “are two countries - England and America. Another country - Russia - is not the enemy at the moment, but is dangerous for both states (that is, for Germany and Japan. - A. N .). At the moment, everything is in order in relations with Russia. Germany believes in this country, but 185 divisions that Germany has at its disposal ensure its security better than treaties do. Thus, Hitler concluded, “German interests and Japan are absolutely parallel in three directions. "

To seek the speedy involvement of Japan in the war - such an arrangement was given in the directive of the German High Command of the Armed Forces No. 24 of March 5, 1941 regarding cooperation with Japan. This document explicitly stated that the goal of German policy was to engage Japan in active operations in the Far East as soon as possible. "" Operation Barbarossa, as stated later, creates especially favorable political and military conditions for this. " the directive made clear that it was an attack by Japan on British possessions, while Germany, attacking the Soviet Union, liberated Japanese troops constrained in the Far East.

During the stay of the Japanese Foreign Minister in Berlin, this attitude was the leitmotif of all conversations with him by Hitler and Ribbentrop. Stressing that England had already been defeated and it was beneficial for Japan to immediately oppose it, the head of the German Reich also drew the attention of the Japanese minister to the fact that England's hope and American aid were England's hope. Mentioning in this connection the Soviet Union, Hitler wanted to avert Japan from signing any political agreements in Moscow. Ribbentrop also tried to instill in Matsuoka the idea of \u200b\u200bthe imminent defeat of England and the liquidation of the British Empire; therefore, Japan should hurry by attacking, say, Singapore. Ribbentrop in every possible way made clear to the interlocutor that the war of Germany against the USSR is inevitable. From here, Matsuoka himself had to come to the conclusion that there was no point in entering into a political agreement with the Soviet Union. After all, Japan’s ally, Germany, takes over ... Ribbentrop explained to Matsuoka: “German armies in the east are ready at any time. If Russia one day takes a position that can be interpreted as a threat to Germany, the Führer will crush Russia. Germany is convinced that the campaign against Russia will end in the absolute victory of German weapons and the complete defeat of the Red Army and the Russian state.The Fuhrer is convinced that in the event of actions against the Soviet Union in a few months there will be no more great power of Russia ... it must be borne in mind that the Soviet Union, despite all the denials, is still carrying out communist propaganda abroad ... The fact remains that Germany must secure its rear for a decisive battle with England ... The German army has practically no opponents on the continent for a possible exception to Russia. "

In a conversation dated March 29, 1941, Ribbentrop assured Matsuoku in his usual provocative manner: "If Russia ever attacks Japan, Germany will strike immediately." Consequently, Japan's security in the north is ensured.

The pressure on Matsuoka turned out to be unrelenting perseverance throughout the stay of the Japanese minister in Berlin on April 4, Matsuoka again talked with Hitler, and on April 5 - with Ribbentrop. Time and again, German ministers assured Matsuoka that England was about to collapse and that peace would be achieved at the cost of her complete surrender. Japan should hurry. Matsuoka assented in understanding, pretending to agree with everything, and asked for help from Japan in armament, in particular in the equipment of submarines. Matsuoka promised his partners to support the plan of attack on Singapore in Tokyo, although during his stay in Berlin he received a warning from the high command about the unwillingness to accept any military obligations, for example, attacks on Singapore. Matsuoka himself proceeded from the calculation that a war with England would not necessarily mean a war with the United States of America. Despite Ribbentrop’s assurances that Germany would ensure Japan’s security in the north, Matsuoka, acting in accordance with the directives received in Tokyo, decided to seek a direct Japan-Soviet agreement. On February 2, the document "On Boosting the Southward Promotion Policy" was approved in Tokyo.

Negotiations on the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese pact resumed on April 8, after Matsuoka returned to Moscow. They were held in the midst of continuing disagreement over the nature of the contract. The Japanese foreign minister insisted on a non-aggression pact. The Soviet side agreed to this subject to the elimination of Japanese concessions in Northern Sakhalin. After much debate, it was decided to sign a neutrality treaty, which was done on April 13, 1941. At the same time, Matsuoka made a written commitment to resolve the issue of concessions in Northern Sakhalin within a few months. Later, in connection with the outbreak of the German-Soviet war, the problem of concessions was no longer returned.

The Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact was approved in Tokyo, since at that time the supporters of expansion in the southern direction were superior. This was expressed in the fact that on June 12, it was decided to intensify the actions of Japan in the south, not stopping before the war with England and the United States of America. The final decision was made 10 days after the German attack on the Soviet Union, at the imperial conference on July 2, 1941.

Introduction

1. Diplomacy of the USSR on the eve of the war.

2. Moscow conference.

3. Tehran Conference.

4. Yalta Conference.

5. Potsdam Conference.

Conclusion

List of references

Introduction

War and diplomacy. These two concepts are, as it were, antipodes. It is no coincidence that it has long been customary to believe that when guns speak, diplomats are silent, and, conversely, when diplomats speak, guns are silent. In reality, everything is much more complicated: during the course of wars, diplomatic activity continues, just as sometimes various diplomatic negotiations are accompanied by military conflicts.

Diplomacy during the Second World War - the largest in the entire history of mankind - is a vivid confirmation of this. Although her fate was decided on the battlefields, and primarily on the main front of the Second World War - the Soviet-German one, diplomatic negotiations, correspondence, conferences during the war played a significant role both in achieving victory over the fascist aggressors and in determining the post-war structure of the world .

The importance attached to diplomacy by the participants of the two military-political unions that had been at war during the war is evidenced, in particular, by numerous bilateral and multilateral negotiations. The Moscow, Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam conferences played an outstanding role in the development and strengthening of the anti-Hitler coalition. The important bilateral meetings of the leading figures of the USSR, the USA and England served the same purpose. The foreign political activity of the states united in the struggle against the fascist bloc is a bright page in the history of world politics.

The military-political union of the USSR, England and the USA fulfilled the task for which it was created: by the combined efforts of the anti-Hitler coalition, in which it played a leading role. The Soviet Union, the fascist bloc led by Germany was defeated. All attempts by fascist diplomacy to split the Soviet-Anglo-American coalition, playing on the differences in the social structure of its members, ended in complete failure. The fruitful cooperation of the Soviet Union, the United States and England ensured the adoption of agreed decisions and the implementation of a number of joint activities on the most important issues of warfare and the post-war peace system.

At the same time, the discussion of a number of issues between the Allies often revealed serious, sometimes fundamental differences and disagreements in the positions of the USSR, on the one hand, the United States and England, on the other. These disagreements were mainly determined by the difference in the goals of the war that the governments of these countries set themselves and which, in turn, stemmed from the very nature of the states participating in the anti-Hitler coalition. In their diplomatic activities, the discrepancies also found a vivid manifestation. Finally, the diplomatic history of the Second World War is of additional interest by the fact that the main characters in it were prominent political figures who left a noticeable mark in the history of their countries.

1. Diplomacy of the USSR on the eve of the war.

2. Moscow conference.

Among the most important milestones of Soviet diplomacy during the war, a number of allied conferences held in Tehran, Moscow, Yalta, Potsdam should be noted. At these conferences, all the features of Soviet diplomacy of the war years were manifested.

The most important questions concerning the reduction of the terms of war and the post-war peace order were discussed at the end of 1943 at a number of international conferences. Among them is the first meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the Soviet Union, the United States and England during the war years, which took place from October 19 to October 30, 1943 in Moscow. The conference had a broad agenda of 17 items, which included all the issues proposed for discussion by the delegations of the USSR, USA and England.

The work of the conference was very intensive: during the conference 12 plenary sessions were held, in parallel with which various drafting groups worked, and expert consultations took place. A number of bilateral meetings of delegations also took place, including with the participation of the head of the Soviet government. The delegations of the USSR, the USA and England submitted a significant amount of documents to the conference.

As a result of the discussion of a wide range of issues at the conference, decisions were made on one of them, on the other - the basic principles were agreed so that they would be further studied through diplomatic channels or in bodies specially created at the conference for this, only the exchange took place opinions.

The main goal of the Soviet government at the conference was the adoption of such joint decisions that would be aimed at the speedy end of the war and the further strengthening of inter-allied cooperation, the Soviet Union proposed to consider at the conference. As a separate agenda item, measures to reduce the time of the war against Germany and its allies in Europe. On the very first day of its work, the head of the Soviet delegation, V. M. Molotov, conveyed to the other participants in the conference concrete proposals of the Soviet Union on this subject. In them, in particular, it was primarily intended “to carry out such urgent measures on the part of the governments of Great Britain and the USA back in 1943, which would ensure the invasion of the Anglo-American armies in Northern France and which, along with powerful strikes by Soviet troops on the main forces of the German army on the Soviet-German front, they must fundamentally undermine the military-strategic position of Germany and lead to a decisive reduction in the terms of the war. " At the conference, the question was clearly posed: whether the promise of Churchill and Roosevelt, which they had made in June 1943 to open a second front in the spring of 1944, remains valid. To answer the Soviet request, the head of the British delegation, A. Eden, received Churchill’s special instruction, in which the latter avoided the direct answer in every possible way, again emphasizing in an exaggerated form the difficulties on the landing route in Western France.

The British Prime Minister instructed the Minister of Foreign Affairs to inform the head of the Soviet Government of the difficulties that the Anglo-American forces in Italy face that may affect the question of the date of the English Channel crossing. Fulfilling Churchill's instructions, Eden visited Stalin and acquainted the latter with the contents of the message of the English prime minister. In response to Eden's assurances that “the prime minister wants to do everything in his power to fight the Germans,” Stalin noted that he had no doubt about that. However, Stalin continued, “the prime minister wants him to get easier things, and we Russians are more difficult. It could be done once, twice, but you can’t do this all the time. "

At the end of the conference, another message arrived in the name of Eden - this time from General G. Alexander from Itazha warning that the failure of the allies there would likely delay the landing of the Channel. On October 27, Eden hastened to report this unpleasant news to Stalin.

Speaking at one of the conference sessions, Generals Ismay (England) and Dean (USA) informed the Soviet side about the decisions taken at the conference in Quebec, and about the preparations for the landing in Western France in England and the USA in accordance with these decisions. Both military representatives determined the success of this operation by various military, meteorological and other factors. Neither the American nor the British delegation gave an exact date for the start of the English Channel crossing operation. “The Soviets took note of our clarifications on military plans,” US Ambassador A. Harriman to Washington reported from the conference, “however, in general, strong relations between us largely depend on their satisfaction with our future military operations. It is impossible to overestimate the importance that they attach strategically to the opening of the so-called second front next spring. I believe that the invitation to the next military conference is essential for the seeds sown at this conference to sprout. It is clear that they will never put up with the situation when they are offered a ready-made Anglo-American solution ... ”

From the discussion of the question of further military operations it became clear that, despite the assurances of Churchill and Roosevelt, the possibility of a new delay in opening a second front was not excluded. The Soviet government decided to return to the question of reducing the time of war during the upcoming meeting of the heads of government of the three powers. An especially secret protocol was signed at the Moscow conference on November 1, 1943, in which, in particular, it was recorded that the Soviet government took note of the statement of Eden and Hell, as well as the statements of Generals Ismay and Dean, “and hopes that the statement in these statements, the plan of the invasion of Anglo-American troops in northern France in the spring of 1944 will be completed on time. "

Thus ended the discussion on opening a second front in Europe. Although the representatives of England and the United States did not make a firm and precise commitment to this agenda item, they agreed to include in the final communiqué of the conference a statement that the three governments recognize as their "primary goal to accelerate the end of the war."

The proposal of the Soviet Union to reduce the time of the war, in addition to the question of the second front, contained two more points: on Turkey’s entry into the war on the side of the anti-Hitler coalition and on the provision of allied air bases in Sweden for military operations against Germany.

Speaking at one of the conference sessions, the head of the Soviet delegation emphasized: "Everything that helps the main question - to reduce the time of the war, is useful to our common cause." Therefore, the Soviet government proposed demanding on behalf of the three powers that Turkey "immediately enter the war and render assistance to the common cause." In the same plan, the Soviet government was considering the possibility of obtaining military bases in Sweden.

However, the delegations of England and the USA did not show interest in the Soviet proposals, kept silent about them for a long time, referring to the lack of instructions, and in the end they declined to make any specific decisions on these proposals.

The attention of the governments of England and the United States was focused not on the question of reducing the time of the war, but on considering the measures they proposed that would ensure for Western states the maximum benefits of victory over the fascist bloc. For London and Washington, it became increasingly apparent that the day was not far off when the Red Army, having expelled the invaders from its territory, would begin to liberate the countries of Europe. The approach of Soviet troops to the state border of the USSR decisively changed the military-political and strategic balance of power in the international political arena. That is why the desire to quickly put his foot in the door leading to neighboring countries of the Soviet Union, was reflected in many proposals of both the English and American delegations. It is no coincidence that many of the questions brought up for consideration by the British delegation at the Moscow conference concerned precisely the situation and policies regarding the countries neighboring the USSR. Here are some of them: "Relations between the USSR and Poland and politics in relation to Poland in general"; “The future of Poland, the Danube and the Balkan countries, including the issue of confederations”; “Policy regarding the territories of the allied countries liberated as a result of the offensive of the allied forces”; “The question of agreements between the main and small allies on post-war issues,” that is, the conclusion of the Soviet-Czechoslovak Union Treaty, etc.

In raising these questions, the British government and, as a rule, the American government, which was in solidarity with it, were guided by no means in the interests of improving relations between the Soviet Union and its neighbors, but were primarily concerned with ensuring the coming to power in the countries to be liberated by the Red Army, various pro-Western politicians and factions. In a conversation with the then Polish ambassador to the United States, Tsekhanovsky, the head of the American delegation K. Halle once said after the Moscow conference that he considered restoring relations between the USSR and the pro-Western emigrant government one of his main tasks at the conference. A. Eden persistently achieved the same during the conference.

The British delegation was particularly active in promoting various plans that were born in London for the creation of federal associations of small European states in Central and Southeast Europe. Speaking at a conference meeting, Eden said: “We must ensure that groups or associations of small states that may arise receive support from all the great powers.”

From the document presented by the British and from the whole course of reasoning of the English minister, the intention emerged of creating an association of small states in eastern Europe that would follow in the wake of Western policy.

London's even more frank desire to intervene in relations between the Soviet Union and its neighbors was manifested in the question of the Soviet-Czechoslovak treaty, which was considered in connection with a special agenda item proposed by England.

The fact is that in the summer of 1943 the British government objected to the trip of the then President of the Czechoslovak Republic to Benes to Moscow with the aim of concluding a Soviet-Czechoslovak friendship, mutual assistance and cooperation agreement allegedly on the basis of an agreement reached in London during the 1942 Anglo-Soviet negotiations . The position of the British was so unconvincing that it did not receive the support of even the Americans.

In the same context, the attempts of the British government to intervene in the nature of Soviet-Yugoslav relations should be considered. At the conference, Eden strongly recommended that the Soviet government establish contact and cooperation with the troops of General Mikhailovich, who had been compromised by cooperation with the Nazi occupiers. The Soviet government resolutely rejected attempts to create an anti-Soviet “sanitary cordon” around the Soviet Union and obstacles to establishing friendly, good-neighborly relations with the countries of Eastern Europe. So, at one of the meetings of the conference, the head of the Soviet delegation emphasized that the question of the relationship between Poland and the USSR — the two neighboring states — first of all concerns these states themselves and must be resolved by them. In the same way, London's intention to intervene in Soviet-Czechoslovak relations was rejected. The Soviet delegation pointed out that there was no agreement between the governments of England and the USSR regarding the impossibility of concluding an agreement between the USSR or England, on the one hand, with any other small state, on the other.

“The Soviet government,” the statement read out by the head of the Soviet delegation, “... considers it a right of both states, both the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom, to preserve peace and resist aggression, conclude agreements on post-war issues with the border allied states, without making it dependent on consultation and coordination between them, since such agreements concern the immediate security of their borders and the respective border states with them, such as , The USSR and Czechoslovakia. " Soon, on December 12, 1943, a Soviet-Czechoslovak treaty of friendship, mutual assistance and post-war cooperation was signed in Moscow.

On the question of creating confederations in Europe, the Soviet delegation made a special statement in which it emphasized that, in the opinion of the Soviet government, the liberation of small countries and the restoration of their independence and sovereignty are one of the most important tasks of the post-war structure in Europe. The statement noted that "such an important step as the federation with other states and the possible renunciation of part of its sovereignty are permissible only in the order of a free, calm and well-thought out expression of the will of the people." The Soviet delegation declared the danger of premature, artificial attachment of small countries to theoretically planned groups. She pointed out that attempts to federate governments that did not express the true will of their peoples would mean imposing decisions that did not correspond to the desires and constant aspirations of the peoples. In addition, the statement emphasized that "some projects of the federations remind the Soviet people of the policy of the sanitary cordon, directed, as you know, against the Soviet Union and therefore perceived by the Soviet people negatively." For these reasons, the Soviet government considered it premature to schedule and artificially encourage the unification of any states in the form of a federation, etc.

The Soviet government also strongly opposed the division of Europe into separate spheres of influence. “As for the Soviet Union,” the head of the Soviet delegation said at the conference, “I can guarantee that we did not give any reason to suppose that he favors the division of Europe into separate zones of influence.” When the Soviet representative raised the question of whether to spread the idea of \u200b\u200babandoning spheres of influence to the whole world, the British delegation preferred to quickly stop discussing the very same agenda item. No decision was made at the conference on the issue of confederations, or on other issues aimed at interfering in relations between the Soviet Union and its neighbors. A. Harriman wrote in Washington about this, that the Russians “are determined to ensure that in Eastern Europe there is nothing like the old concept of a“ sanitary cordon ”. "Molotov told me that the relations they expect to establish with neighboring countries do not impede the establishment of friendly relations with England and us."

At the same time, when it came to the situation in the countries of Western Europe, the liberation of which was begun by the Anglo-American troops or in which the landing of these troops was supposed, then the position of the delegations of England and the USA was completely different. Here they tried in every possible way to ensure a position that would allow England and the United States to fully command in these countries, implementing a separate policy there at their own discretion. Take, for example, the situation in Italy, which was considered at the conference in accordance with its agenda.

By the time of the conference, a significant part of the Italian territory had been cleared of fascist troops. In the liberated part of the country, the American and British authorities continued to pursue a separate policy that was anti-democratic. The actions of the Anglo-American occupation authorities in Italy from the very first days of their creation were criticized both by the democratic circles of Italy and by the world community. In this regard, the Soviet delegation wished to receive comprehensive information on the implementation of the ceasefire agreement with Italy and presented concrete proposals regarding Italy aimed at eliminating the remnants of fascism in the country and its democratization. The British and Americans, like on the eve of the conference, tried to present the situation in Italy in a pink light. However, as a result of the perseverance of the Soviet delegation, its proposals were included in the Declaration of Italy signed at the Moscow conference. The adoption of this important document, as well as the creation of an Advisory Council on Italy, consisting of representatives of England, the USA, the USSR and the French Committee for National Liberation, followed by the inclusion of representatives of Greece and Yugoslavia, was a positive factor. The actions of the American and British authorities in the part of Italy liberated from German troops were somewhat limited.

Or take another question - about the situation in France, which was also considered at the conference. The English delegation introduced at the conference a document entitled “The Basic Management Scheme of a Liberated France”. According to this scheme, the supreme power in liberated France was to belong to the commander in chief of the allied forces; as for the civil administration, it would be carried out by French citizens, but under the control of the allied commander in chief and only to a limited extent. When deciding civil matters, the commander in chief should consult with the French military mission, located at his headquarters. In this way. The French Committee of National Liberation actually eliminated this scheme from the management of a liberated France, and the creation of an occupation regime was envisaged on its territory. The proposal of the English representatives was approved by the American side.

The French National Liberation Committee itself was not acquainted with the English draft, and since Eden sought approval of this document by the Moscow conference, his desire to obtain the consent of the Soviet Union to the unlimited power of Anglo-American bodies in France became obvious. The Soviet government, of course, could not agree with this proposal, as a result of which the “main scheme” was not approved by the conference. This conference decision paper was referred to the established European Advisory Commission.

The position of the US government at the Moscow conference was not much different from the position of the British government. As a rule, Americans supported the proposals and ideas expressed by the British. At the same time, some differences were visible between the positions of the USA and England. While England's interests were concentrated mainly on European issues, the United States put forward issues related to the establishment of the post-war order in the world as a whole. Washington primarily sought to completely eliminate its potentially most dangerous adversary - Germany. In addition, the Americans proposed making decisions at the conference on a wide range of economic problems (food, agriculture, transport, communications, finance, trade, etc.) of the post-war reconstruction period.

True, at the conference, the American delegation was somewhat more passive than its English colleagues. This was partly due to the fact that the US delegation was led by Secretary of State C. Hull, who was directly involved in the discussion of the problems of trilateral relations for the first time and, apparently, still had a load of isolationism on him. At times at the conference he avoided expressing his point of view on certain European issues, considered them to be a matter to be settled between England and the USSR, very often referred to the lack of a position, more than once proposed reducing the time for discussing certain issues, etc. In practice, all the important negotiations at the conference took place between the heads of the Soviet and British delegations. Cordell Hell, as the English ambassador to Moscow Clark Kerr told London, “looked and moved like a magnificent old eagle” and “was introduced ... with all due respect to the substance of the decisions that were made” by his two colleagues. This was perhaps the last important international meeting at which not the Americans, but the British spoke on behalf of the West in negotiations with the Soviet Union.

The most significant proposals made by the Americans concerned the German problem and the declaration of the four states on the issue of global security. On October 23, 1943, Hell presented to the conference a detailed proposal for the treatment of Germany. It consisted of three parts. The first - included the basic principles of the unconditional surrender of Germany, the second dealt with the treatment of Germany during the armistice period, and finally, the third laid down the foundations of the future political status of Germany. The US government has proposed decentralizing the German political structure and encouraging various movements within Germany itself, in particular the movement "in favor of reducing the Prussian influence on the Reich."

Eden spoke at the conference endorsing the American proposal, setting out at a meeting on October 25 a plan by the British government regarding the future of Germany. “We would like to divide Germany into separate states,” said Eden, “in particular, we would like to separate Prussia from the rest of Germany. Therefore, we would like to encourage those separatist movements in Germany that can find their development after the war. Of course, it’s difficult now to determine what opportunities we will have for the implementation of these goals, and whether it will be possible to achieve them by using force. ”

Regarding the position of the Soviet Union on the future of Germany, speaking at one of the meetings of the conference, the head of the Soviet delegation emphasized that the USSR occupies a special position in this matter. “Since the German troops are still located in a large part of the territory of the Soviet Union,” he said, “we especially feel the need to crush the Nazi army and throw it out of our territory as soon as possible.” Therefore, the Soviet government considered it inadvisable at the moment to make any statements that could lead to toughening of the German resistance. In addition, as stated by Molotov, the Soviet government has not yet come to any definite opinion on the question of the future of Germany and continues to study it carefully. A. Harriman reported to Washington that; in his opinion, “the Russian approach to Germany, as it turned out at the conference, is basically satisfactory. Of course, it is doubtless that they are inclined to achieve the complete destruction of Hitler and Nazism. They are ready to deal with Germany on the basis of tripartite responsibility ... ” Apparently, under the influence of the ideas expressed by the Soviet delegation, the conference participant, American F. Mosley, noted the existence of doubts about the benefits of dismemberment; the conference expressed "an increasing tendency to keep this question open."

The central theme of the Moscow conference was to strengthen cooperation between the main states of the anti-Hitler coalition. Representatives of the Soviet Union especially emphasized the need to expand and improve cooperation. So, at one of the meetings, the head of the Soviet delegation, touching on this topic, said: “We have the experience of cooperation, which is of the greatest importance, - the experience of joint struggle against a common enemy. "Our peoples and our states and governments are interested in taking measures now that would prevent aggression and violation of peace in the future, after this grave war." The Soviet government considered honest, conscientious fulfillment of allied obligations the main condition for strengthening cooperation between the three great powers. Thus, in a conversation between the head of the Soviet Government and the British Foreign Minister on October 21, 1943, the question of Anglo-American supplies to the Soviet Union and the correspondence between Stalin and Churchill on this subject was raised. Referring to this correspondence, Stalin said: “We understood this so that the British consider themselves free from their obligations that they took under an agreement with us, and consider sending transports a gift to us or grace. It is indigestible for us. "We do not want gifts or mercy, but we simply ask to fulfill our obligations to the extent possible." In raising the question of reducing the time of the war, the Soviet Union also sought to ensure that the allies - the USA and England - fulfilled the obligations that they had undertaken before the Soviet Union in various agreements and arrangements.

A few days later, in another meeting with Stalin, when the British Foreign Minister called the British “a little boy”, and the USSR and the United States “two big boys,” the head of the Soviet government remarked that this definition was an incorrect expression. “In this war,” he said, “there are neither small nor large. Everyone is doing their job. We would not have developed such an offensive if the Germans were not threatened by an invasion in the West. Already one fear of invasion, one specter of invasion does not allow Hitler to significantly strengthen his troops on our front. In the West, only a ghost holds the Germans. Our share fell on a more difficult matter. ”

The adoption of a number of important decisions by the conference reflected the willingness of the participants in the Moscow conference to continue the policy of cooperation. These include, first of all, the Declaration of the Four States on the issue of global security, which laid the foundation for the creation of the United Nations.

Since it was a question of adopting a document that was important for all the states of the anti-Hitler coalition, it was deemed necessary to invite the representative of China to sign the adopted declaration. It stated that after the end of the war, the efforts of the Allies will be aimed at achieving peace and security, that an international organization for ensuring peace and security will be created in the near future, and that in the post-war politics the powers will not use military means to resolve disputed issues without mutual consultation. In this declaration, the Governments of the four Powers solemnly proclaimed that they would consult and cooperate with each other and with other members of the United Nations with a view to reaching a feasible universal agreement on post-war arms control.

In this first joint statement of the great powers on the need to create an international organization for the preservation of peace and security of peoples, great changes in the international situation that have occurred since the beginning of the Second World War were reflected. The historic victories of the Soviet armed forces in 1942-1943 and the increased international authority of the USSR led to plans that the creation of Anglo-American police forces in the post-war period, which were hatched by Washington and London at the beginning of the war, to be futile. In the wide system of international cooperation and security proposed by the four powers, all peace-loving states, large and small, should have taken an active part - a principle that has invariably been upheld by the Soviet state from the very first days of its existence.

The Soviet delegation at the conference made an important contribution to solving the problem of creating an international security organization, proposing to form a commission in Washington, London or Moscow consisting of representatives of the three powers, and after a while at a certain stage of work, and representatives of other United Nations, for preliminary joint development of issues, associated with the establishment of a universal international organization.

The Moscow Conference also considered other issues, in particular, about a general line of behavior in the event of attempts by peaceful sounding by enemy states. In discussing this issue, the head of the USSR delegation stated that the Soviet government categorically objected to conducting any negotiations with the allies of Hitler Germany on half-measures. “We believed and still believe that negotiations can only be on surrender,” the Soviet representative said. - All sorts of other negotiations are worthless negotiations, they can even interfere with the solution of the main issue. During the current war, negotiations may not be about a ceasefire, but only about surrender, about surrender ”

According to the decision adopted at the Moscow conference, the three governments pledged to “immediately inform each other about all kinds of trial proposals of the world”, as well as to consult with each other to coordinate actions regarding such proposals.