Biography. Glinka brothers: geniuses of air combat Glinka brothers Dmitry and Boris

USSR USSR

Boris Borisovich Glinka(-) - Colonel of the Soviet Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union ().

Biography

In total, during the war, Glinka shot down 30 planes personally and 1 in a group. In one of the battles at the end of the war he was wounded. After the end of the war, Glinka continued to serve in Soviet Army. In 1952 he graduated from the Air Force Academy, after which he served at the Borisoglebsk Military Aviation School, then at the Cosmonaut Training Center. He lived in the village of Chkalovsky (now within the boundaries of Shchelkovo) in the Moscow region. He died on May 11, 1967, and was buried at the Grebenskoye cemetery in Shchelkovo.

Write a review of the article "Glinka, Boris Borisovich"

Notes

Literature

- Heroes Soviet Union: Brief biographical dictionary / Prev. ed. collegium I. N. Shkadov. - M.: Voenizdat, 1987. - T. 1 /Abaev - Lyubichev/. - 911 p. - 100,000 copies. - ISBN ex., Reg. No. in RKP 87-95382.

- Andreev S. A. What they accomplished is immortal. Book 2. M.: graduate School, 1986.

- Vorobyov V. P., Efimov N. V. Heroes of the Soviet Union. Directory - St. Petersburg, 2010.

- Heroes of the fiery years. - Book 1. - M.: Moscow worker, 1975.

- Golubev G. G. My friends are pilots. - M.: DOSAAF, 1986.

- Golubev G. G. On verticals. - Kharkov: Prapor, 1989.

- Both general and private. - Dnepropetrovsk: Promin, 1983.

- Wings of the Motherland. - M.: DOSAAF, 1983.

- Who was who in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. Kr.sp.-M.: Respublika, 1995.

- On the edge of the possible. - 2nd ed., rev. and additional - M.: “Limb”, 1993.

- Fire years. - Ed. 2nd, revised and additional - M., 1971.

- Stepanenko V. I. People from the legend. - M.: Knowledge, 1975.

An excerpt characterizing Glinka, Boris Borisovich

Directly from the governor, Nikolai took the saddlebag and, taking the sergeant with him, rode twenty miles to the landowner's factory. Everything during this first time of his stay in Voronezh was fun and easy for Nikolai, and everything, as happens when a person is well disposed, everything went well and went smoothly.The landowner to whom Nikolai came was an old bachelor cavalryman, a horse expert, a hunter, the owner of a carpet, a hundred-year-old casserole, an old Hungarian and wonderful horses.

Nikolai, in two words, bought for six thousand and seventeen stallions for selection (as he said) for the horse-drawn end of his renovation. Having had lunch and drunk a little extra Hungarian, Rostov, having kissed the landowner, with whom he had already gotten on first name terms, along the disgusting road, in the most cheerful mood, galloped back, constantly chasing the coachman, in order to be in time for the evening with the governor.

Having changed clothes, perfumed himself and doused his head with cold milk, Nikolai, although somewhat late, but with a ready-made phrase: vaut mieux tard que jamais, [better late than never] came to the governor.

It was not a ball, and it was not said that there would be dancing; but everyone knew that Katerina Petrovna would play waltzes and ecosaises on the clavichord and that they would dance, and everyone, counting on this, gathered at the ballroom.

Provincial life in 1812 was exactly the same as always, with the only difference that the city was livelier on the occasion of the arrival of many wealthy families from Moscow and that, as in everything that was happening in Russia at that time, it was noticeable some kind of special sweepingness - the sea is knee-deep, the grass is dry in life, and even in the fact that that vulgar conversation that is necessary between people and which was previously conducted about the weather and about mutual acquaintances, was now conducted about Moscow, about the army and Napoleon.

The society gathered from the governor was the best society in Voronezh.

There were a lot of ladies, there were several of Nikolai’s Moscow acquaintances; but there were no men who could in any way compete with the Cavalier of St. George, the repairman hussar, and at the same time the good-natured and well-mannered Count Rostov. Among the men was one captured Italian - an officer of the French army, and Nikolai felt that the presence of this prisoner further elevated the importance of him - the Russian hero. It was like a trophy. Nikolai felt this, and it seemed to him that everyone was looking at the Italian in the same way, and Nikolai treated this officer with dignity and restraint.

As soon as Nicholas entered in his hussar uniform, spreading the smell of perfume and wine around him, he himself said and heard the words spoken to him several times: vaut mieux tard que jamais, they surrounded him; all eyes turned to him, and he immediately felt that he had entered into the position of everyone’s favorite that was due to him in the province and was always pleasant, but now, after a long deprivation, the position of everyone’s favorite intoxicated him with pleasure. Not only at stations, inns and in the landowner’s carpet were there maidservants who were flattered by his attention; but here, at the governor’s evening, there was (as it seemed to Nikolai) an inexhaustible number of young ladies and pretty girls who were impatiently waiting for Nikolai to pay attention to them. Ladies and girls flirted with him, and from the first day the old women were already busy trying to get this young rake of a hussar to marry and settle down. Among these latter was the governor’s wife herself, who accepted Rostov as a close relative and called him “Nicolas” and “you.”

Katerina Petrovna really began to play waltzes and ecosaises, and dances began, in which Nikolai even more captivated the entire provincial society with his dexterity. He surprised even everyone with his special, cheeky style of dancing. Nikolai himself was somewhat surprised by his manner of dancing that evening. He had never danced like that in Moscow and would even have considered such an overly cheeky manner of dancing indecent and mauvais genre [bad taste]; but here he felt the need to surprise them all with something unusual, something that they should have accepted as ordinary in the capitals, but still unknown to them in the provinces.

Throughout the evening, Nikolai paid most of his attention to the blue-eyed, plump and pretty blonde, the wife of one of the provincial officials. With that naive conviction of cheerful young people that other people's wives were created for them, Rostov did not leave this lady and treated her husband in a friendly, somewhat conspiratorial manner, as if they, although they did not say it, knew how nicely they would get together - then there is Nikolai and this husband’s wife. The husband, however, did not seem to share this conviction and tried to treat Rostov gloomily. But Nikolai’s good-natured naivety was so boundless that sometimes the husband involuntarily succumbed to Nikolai’s cheerful mood of spirit. Towards the end of the evening, however, as the wife's face became more ruddy and livelier, her husband's face became sadder and paler, as if the share of animation was the same in both, and as it increased in the wife, it decreased in the husband .

Glinka Dmitry Borisovich (1917-1979).

Military pilot, twice Hero of the Soviet Union (1943).

Born on December 12, 1917 in a working-class family, in the village of Aleksandrov Dar, now the village of Rakhmanovka, Dnepropetrovsk region. Graduated from incomplete high school. At the age of 13, he came to the MOPR mine, where his father and older brother worked.

In 1937 he graduated from the Krivoy Rog flying club.

Since 1937 in the Red Army.

In 1939 he graduated from the Kachin Military Aviation Pilot School. Served in the 45th IAP (based in Baku), flew I-16. Completed flight commander courses.

Dmitry received his baptism of fire in January 1942 in Crimea, as part of the 45th Fighter Aviation Regiment, equipped with Yak-1 aircraft. There he made an initiative by shooting down a Ju-88. In heavy battles on 4 fronts (Crimean, Southern, North Caucasian, Transcaucasian) from January 9 to September 19, 1942, the regiment lost 30 aircraft and 12 pilots, destroying 95 enemy aircraft. Dmitry Glinka then shot down 6 enemy vehicles. In May he was hit and wounded. I woke up in the arms of infantrymen, not remembering how I descended with a parachute. The concussion turned out to be so serious that doctors flatly forbade him to fly. He spent about 2 months in hospitals.

His return coincided with the arrival of young pilots in the unit, and, having carefully looked at the replenishment, he chose as his wingman a thin boy who looked like a gypsy, Ivan Babak. There were days when they made 4-5 combat missions.

Soon Dmitry became the first ace in the regiment, he was assigned to lead large groups of fighters into battle.

In January 1943, the regiment was rearmed with Airacobras, and on March 10 it was thrown into battle in the Kuban. Here the regiment became the Guards - the 100th GvIAP, and the assistant commander for the air and rifle service of the Guard, Captain D. Glinka, proved himself to be an outstanding master of vertical maneuver. Flying an Airacobra with tail number “21,” Dmitry sowed real terror among enemy pilots. Within a few weeks (by May 1943), he shot down 21 enemy aircraft, becoming one of the most successful pilots in this battle. Here, in Kuban, in a big battle, where more than 100 aircraft took part on both sides, Dmitry, attacking from behind - from below, from a hill, successively shot down 2 Ju-88 bombers, but he himself was shot down for the second and last time during the war, wounded , jumped out with a parachute. A week later he returned from the hospital still in bandages.

For exemplary performance of combat missions of the command, courage, bravery and heroism shown in the fight against German fascist invaders, By the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated April 24, 1943, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union with the Order of Lenin and the medal " Gold Star"(Gold Star medal No. 906).

A man of great physical strength, endurance and passion, in the stubborn April battles he made several combat missions a day, once bringing their number to 9! After that, he slept for almost a day and a half and was diagnosed "severe fatigue" was suspended from flying for a week.

By decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated August 24, 1943, D.B. Glinka was awarded the second Gold Star medal for new exploits.

After almost six months of vacation, study and replenishment, the pilots of the 100th Guards Aviation Regiment took part in the Iasi-Kishinev operation on the southern segment of the front. During these battles, the regiment's pilots shot down about 50 enemy aircraft, and Dmitry Glinka's personal score grew to 46 victories. So, in May 1944, in one of the battles of a group of 12 Airacobras with 45 Ju-87 dive bombers and fighters covering them, Dmitry shot down 3 aircraft at once. In total, during a week of intense fighting near Iasi, he won 6 victories.

In July 1944, having flown on a transport Li-2 as part of 5 pilots of the 100th Guards IAP to pick up repaired aircraft, Dmitry Glinka almost died in a plane crash. Arriving at the airfield a few minutes before departure, Glinka and his companions sat on airplane covers in the tail of the Li-2 (all seats in the cabin were already occupied). During the flight, the plane hit the top of Kremetskaya Mountain, covered with clouds, and crashed. All crew members and passengers were killed. Only five pilots from Glinka’s group survived, who were saved only by the fact that they were positioned at the very rear of the machine. All of them received severe bruises and wounds. Dmitry suffered especially. He was unconscious for several days and was treated for almost 2 months.

After recovery, Dmitry Glinka continued his combat activities and won many more victories. So, during the Lvov-Sandomierz operation, he managed to destroy 9 German vehicles. In the battles for Berlin, he shot down 3 planes in one day, and won his last victory on April 18, 1945, at point-blank range, from 30 meters, shooting down an FW-190 fighter.

Dmitry Glinka ended the war having completed about 300 combat missions and conducted more than 100 air battles. The brave pilot has personally shot down 50 enemy aircraft (9 of them on the Yak-1, the rest on the Airacobra).

After the war, Dmitry Borisovich served in aviation for a long time, commanded a regiment, and then was deputy commander of an aviation division.

In 1951 he graduated from the Air Force Academy.

In 1960, he was demobilized with the rank of Guard Colonel. Many famous combat pilots, having firmly linked their fate with aviation, exchanged the cockpits of formidable fighters, attack aircraft and bombers for the cockpits of helicopters and passenger, ambulance and agricultural aircraft. Twice Hero of the Soviet Union D.B. Glinka sat at the helm of the passenger liner.

Deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the 2nd convocation.

Lived in Moscow. Died March 1, 1979. He was buried in Moscow, at the Kuntsevo cemetery (section 9-3).

Awards:

- two medals “Gold Star” of the Hero of the Soviet Union (04/24/1943 and 08/24/1943);

-Order of Lenin (1943);

-five Orders of the Red Banner of Battle (September 1942, October 1942, 1943, 1944, 1955);

-two Orders of the Red Star (1955, 1956);

-Order of Alexander Nevsky (1945);

-order Patriotic War 1st degree (1943).

Memory:

The name of Dmitry Glinka was assigned to the Sukhoi Superjet 100 aircraft with the number RA-89046.

In the city of Krivoy Rog there is a bronze monument-bust of Glinka and the street is named in his honor.

List of sources:

Website "Heroes of the Country". Glinka Dmitry Borisovich.

I.I.Babak. Stars on the wings.

Between them, Dmitry and Boris Glinka shot down 80 enemy aircraft and received three Gold Star medals.

Today, the names of heroic pilots are little known to the general public. Meanwhile, Dmitry Glinka became the seventh most successful Soviet ace during the Great Patriotic War, having shot down 50 enemy aircraft, and repeat the performance of his younger brother Boris Glinka Only a serious injury prevented him. He had “only” 30 victories to his name.

The sky is calling

When in the family of a Krivoy Rog miner Boris Glinka sons were born in 1914 and 1917; it seemed that both of them were destined for the fate of hereditary miners.

Having graduated from seven classes in 1928, Boris got a job as a worker at a mine, where he showed remarkable organizational skills, for which he was sent to study at a mining technical school. Already in 1934, the 20-year-old guy graduated from technical school and was transferred to the position of shift foreman at the mine.

But his passion led him to the flying club, and then to the Civil Air Fleet pilot school in Kherson, from which he successfully graduated in 1936. Boris was called to military service and were sent to study at the Odessa military aviation base. The command immediately drew attention to the basic knowledge and seriousness of the young pilot.

The youngest, Dmitry, was not far behind. At the age of 13, after graduating from school, he also went into slaughter, and then, after training at a local flying club, he went to enroll in the Kachin Flight School. Having received a diploma as a military pilot, the guy remained in the army, mastering the techniques of piloting and air combat on obsolete I-16 fighters.

Brotherly War

The brothers met the Great Patriotic War in different ways. Boris, despite numerous reports asking to be sent to the active army, was evacuated to Baku along with the school. He trained young pilots who had to repel the fascist aces who had never known defeat in the skies of Western Europe.

Dmitry immediately found himself in the thick of things. As early as August 1941, he flew several combat missions in the I-16 during the Soviet invasion of northern Iran. This successful special operation made it possible to break through the “Iranian corridor”, through which Western military equipment, ammunition, equipment and food were supplied to the USSR. And most importantly, aviation gasoline, which our Air Force was sorely lacking.

On April 9, 1942, the first red star was painted on the fuselage of his fighter for the downing of a German Junkers 88 bomber.

May 9, 1942, exactly three years before Great Victory, the young pilot, in an unimaginably tough battle over the Arabat Spit, shot down three more enemy bombers, bringing his own victory tally to six.

True, German fighters that appeared from behind the clouds also shot down Dmitry Glinka’s plane. The wounded pilot, who managed to jump out of the burning fighter, woke up in the hospital only two days later. Doctors advised him to forget about flying forever, but in violation of all orders he returned to the location of his regiment. The very next day, July 13, Dmitry destroyed the Heinkel 111 bomber, which was considered practically indestructible.

Meeting in Baku

In September 1942, the battle-worn regiment was transferred to rest and reorganize near Baku, in which Dmitry, who already had 11 victories to his credit, managed to meet with his brother.

There are different versions of this meeting, but what is known is that as a result of lengthy negotiations, commander Dmitry Ibragim Dsusov managed to persuade the head of the training center to let Boris Glinka go to the front.

The brothers, who switched to Airacobras received under Lend-Lease, created a real sensation during their first joint flight. The fact that Dmitry managed to destroy two Junkers-88 bombers did not particularly surprise anyone. But Boris’s two victories over the same bomber and the Messerschmitt-109 fighter spoke of the enormous potential of this pilot.

During the battle for the Caucasus, Dmitry Glinka proposed flying out on combat duty in a “Kuban whatnot.” Soviet fighters followed in three air echelons - the lower one attracted the attention of the enemy, the middle one engaged him in an air battle, and the upper one carried out lightning attacks, destroying enemy fighters and bombers.

In just a few weeks, 18 new stars appeared on the fuselage of Dmitry Glinka’s fighter, and his older brother Boris had 14.

Risen from the Dead

On April 15, 1943, Dmitry Glinka’s group entered into an unequal battle, during which the pilot personally shot down three Messers, but he himself was shot down, his plane crashed into a mountain. Boris, who flew out to help his brother, was sure that he was no longer alive, and he fought especially desperately. He managed to destroy two bombers and a fighter, and in total the enemy lost 20 aircraft.

The regiment's soldiers vowed to avenge the death of their comrade, and were shocked when, a few days later, he returned to his unit, exhausted. It turned out that at the last moment he managed to bail out. But upon landing, the pilot received a strong blow and survived only thanks to local residents, who carried him to the nearest hospital using parachute fabric.

On April 24, the regiment read out an order conferring the title of Hero of the Soviet Union on Guard Captain Dmitry Glinka. His “airacobra” with tail number 21 was known to the entire front, and exactly three months later the second Hero Star appeared on Dmitry’s chest. In the interval between these two dates, on May 24, Guard Lieutenant Boris Glinka, who was rapidly catching up with his younger brother, received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

Their call signs: “I am DB” (Dmitry) and “I am BB” (Boris) terrified young Luftwaffe pilots who preferred to flee without engaging in direct conflict with their brothers.

Black July '44

Unfortunately, on July 16, 1944, Boris, who had shot down 30 enemy aircraft, and was left unattended by an inexperienced wingman, was subjected to a sudden attack from above. The fighter practically fell apart in the air, and the pilot who jumped out with a parachute hit the wreckage hard. He remained alive, but never rose into the sky again.

Subsequently, he worked as a teacher at the Borisoglebsk Military Aviation School and until his death on May 11, 1967, he served in the cosmonaut corps. He was only 52 years old, most of which the hero gave to his homeland.

July 1944 was also unlucky for Dmitry. A group of pilots led by him was sent to the rear to receive new fighters. By an incredible coincidence, all the seats in the transport Li-2 were occupied and the pilots had to sit on aircraft covers dropped at the very tail of the plane.

This saved their lives when, due to a pilot error, the plane crashed into Kremenets Mountain. All crew members and passengers were killed, with the exception of five.

After the hospital and recovery, Dmitry returned to his unit and continued to beat the Nazis. The pilot won his last victory, which became his fiftieth, in the skies over Dresden. He took part in the Victory Parade and threw at the mausoleum of V.I. Lenin standards of the defeated Third Reich.

The twice Hero of the Soviet Union continued his military service in various command positions and retired only in 1960 as a result of the third large-scale reduction of the USSR Armed Forces.

The legendary ace died on March 1, 1979. He was buried at the Kuntsevo memorial cemetery in Moscow.

Born on September 14 (27), 1914 in the village of Aleksandrov Dar (now the city of Krivoy Rog, Dnepropetrovsk region of Ukraine). He graduated from the 7th grade of school in 1928. Since 1929 he worked as a miner at a mine in Krivoy Rog. In 1934 he graduated from the Krivoy Rog Mining College. He worked at the same mine as a shift technician, mining technician, and site manager. In 1936 he graduated from the Krivoy Rog flying club. In the same year he graduated from the Civil Air Fleet pilot school in the city of Kherson and remained there as an instructor pilot. Since December 31, 1939 in the ranks of the Red Army. In 1940 he graduated from the Odessa Military Aviation Pilot School. Served in the Konotop military aviation school: instructor pilot, since May 1941 - flight commander.

From June 1941, Lieutenant B.B. Glinka on the fronts of the Great Patriotic War, until August 1941, participated in the air defense of the Konotop railway junction and city. Then, together with the school, he was evacuated to the North Caucasus. From February 20, 1943, he fought as part of the 45th IAP (on June 17, 1943, transformed into the 100th Guards IAP): flight commander, from May 1943 - squadron adjutant. Flew in an Airacobra.

By May 1943, the adjutant of the squadron of the 45th Fighter Aviation Regiment (216th Mixed Aviation Division, 4th Air Army, North Caucasus Front), Lieutenant B.B. Glinka, made 33 combat missions and personally shot down 10 enemy aircraft. By decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR dated May 24, 1943, he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal.

In August 1943, Senior Lieutenant B.B. Glinka was appointed deputy squadron commander. On September 1, 1943, he was shot down in an air battle, wounded and made an emergency landing on a damaged aircraft, during which he received serious injuries. Returned to duty a few months later. Since January 1944, Captain B.B. Glinka has been deputy regiment commander.

From June 1944 - commander of the 16th Guards IAP (9th Guards IAD), where he continued to fly the Airacobra. On July 14, 1944, Guard Major B.B. Glinka was shot down in an air battle, jumped out by parachute, but hit the stabilizer and received serious injuries (a fracture of the right leg and right hand), was treated for a long time and never flew again. In total, he performed about 200 combat missions, in air battles he personally shot down 27 and 2 enemy aircraft as part of a pair. He fought on the North Caucasus, Southern, 4th, 2nd Ukrainian and 1st Ukrainian fronts.

After the war he continued to serve in the Air Force. Since 1946 - senior inspector-pilot for piloting technique and flight theory of the 6th Guards IAK (2nd Air Army, Central Group of Forces), then - in the same position in the 303rd IAD (1st Air Army, Belarusian military district). In 1947 he left for study. In 1952 he graduated from the Air Force Academy. Since 1952, Guard Colonel B.B. Glinka has been the deputy head of the Frunzensky Military Aviation School of Pilots for flight training. Since February 1953 - deputy commander of the 13th Guards IAD (73rd Air Army). Since August 1957 - Deputy Head of the Borisoglebsk Red Banner Military Aviation School as a flight training pilot. Since February 1961, he served in the Cosmonaut Training Center - head of the command post of Space Flight Control, assistant head of the Flight and Space Training Department for flight training, assistant head of the 3rd Department of the Cosmonaut Training Center for flight training. He lived in the village of Chkalovsky (now within the city of Shchelkovo) in the Moscow region. Died May 11, 1967. He was buried in the city of Shchelkovo at the Grebenskoye cemetery. On the Walk of Fame in Kherson his name is among the Heroes of the Kherson region.

Awarded the orders: Lenin (05/24/1943), Red Banner (04/05/1943, 04/24/1943, 11/06/1943), Patriotic War 1st degree (05/31/1946), Red Star (12/30/1956); medals.

* * *

List of famous aerial victories of B. B. Glinka:

| D a t a | Enemy | Plane crash site or air combat | Your own plane |

| 10.03.1943 | 1 Yu-88 | south-eastern outskirts of Abinskaya | "Airacobra" |

| 1 Me-109 | north of Abinskaya | ||

| 19.03.1943 | 1 Me-109 | south of Petrovskaya | |

| 22.03.1943 | 1 Me-109 | to the east is the Gubernatorsky farmstead | |

| 1 Me-109 | northwest of Slavyanskaya | ||

| 11.04.1943 | 1 Me-109 | Abinskaya | |

| 12.04.1943 | 1 Yu-88 | Lvovskaya | |

| 15.04.1943 | 1 Yu-88 | northeast of Krymskaya | |

| 1 Me-109 | northwest of Gladkovsky | ||

| 1 Me-109 | Kyiv | ||

| 26.05.1943 | 1 Me-109 | southwest of Kievskoye | |

| 27.05.1943 | 1 Me-109 | north of Gladkovsky | |

| 1 Me-109 | Kyiv | ||

| 1 FV-189 | west of Chernoerkovskaya | ||

| 18.08.1943 | 1 Me-109 | Krasny Liman | |

| 23.08.1943 | 1 FV-189 (paired) | northwest of Petrovskaya | |

| 26.08.1943 | 1 FV-189 (paired) | Ivanovka | |

| 1 Me-109 | southwest of Donetsko-Amvrosievka | ||

| 28.08.1943 | 1 Yu-88 | Fedorovka | |

| 29.08.1943 | 1 FV-190 | northeast of Fedorovka | |

| 30.08.1943 | 2 Yu-87 | southeast of Shcherbakov | |

| 31.08.1943 | 1 Me-109 | Vanyushkin | |

| 2 Me-109 | Fedorovka | ||

| 1 Me-109 | west of Fedorovka | ||

| 01.09.1943 | 1 Yu-87 | Fedotovka | |

| 04.06.1944 | 1 FV-190 | west of Zahorn | |

| 14.07.1944 | 1 Me-109 | Pigs - Horochow | |

Total aircraft shot down - 27 + 2; combat sorties - about 200. |

|||

From photographic materials of the war years:

From wartime press materials:

Just a story: I thank comrade Vyacheslav Czechsky for the information.

Many families fought in the Red Army: fathers and sons, brothers and sisters, and even grandfathers and their grandchildren. Many became world famous, such as brother and sister Heroes of the Soviet Union Zoya and Alexander Kosmodemyansky or two famous pilot brothers Hero of the Soviet Union Boris and twice Hero of the Soviet Union Dmitry Glinka.

From my dear mine to the field of war -

Rushing to formidable heights

Winged Glinka Boris sons,

Our brave pilots.

From “A Word to the Great Stalin from the Ukrainian People”

12/14/1944

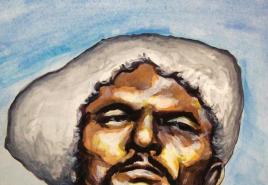

Glinka brothers: Dmitry (left) and Boris (right)

Dmitry became the seventh most successful Soviet fighter ace, and his older brother Boris also became a pilot, having shot down enough Germans to be awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

The brothers were born in the village of Alexandrov Dar, which later merged with Krivoy Rog. The eldest was born in September 1914, two weeks after the outbreak of the First World War. Junior - December 10, 1917. The family had to endure both the German occupation in 1918 and the rampant anarchist movement led by Nestor Makhno during Civil War, and mass famine in the USSR, which raged in 1932-33 in Ukraine, Belarus, the North Caucasus, the Volga region, the Southern Urals, Western Siberia, Kazakhstan and other regions of the huge country.

Boris graduated from seven classes of the Krivoy Rog school in 1928 and immediately went to the coal mine, where his father, a professional miner, worked. The young man graduated from a mining technical school in 1934, after which he worked in a mine as a shift foreman. However, his craze for aviation led him first to the flying club, and then to the Civil Air Fleet pilot school in Kherson, from which he graduated in 1936, after which he remained to work there as an instructor.

Dmitry followed in his footsteps. At the age of 13, he was already working at the MOPR mine next to his father and brother. Boris had just graduated from the Krivoy Rog flying club when Dmitry appeared there, and three years later he became a graduate of the Kachinsky Flight School.

On the very eve of 1940, Boris was drafted into the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army and sent to the Odessa Military Aviation Pilot School, where, after studying for one year, he was left to serve as an instructor pilot.

The brothers had different characters. Lively, very active, cheerful Boris and silent, unhurried, seemingly in no hurry, but always on time, Dmitry. Their service during the war also turned out differently. Boris was stuck in school for a long time. He was an excellent instructor, and, despite his numerous reports asking to be released to the front, the authorities did not want to part with him.

Dmitry joined the active army in June 1941. He did not go through instructor school, but compensated for this with hundreds of training missions on the I-16 fighter. Finally, in December, the long-awaited flight to the front in Crimea, to the 45th Fighter Aviation Regiment, took place. We had to quickly master new equipment, because the regiment flew Yak-1 aircraft.

The first success was achieved on April 9, 1942. In the battle over the Arabat Spit, Dmitry shot down a German Ju-88 bomber with a well-aimed burst. No one could call this victory an accident. It was clear to everyone that a new super-pilot had appeared in the sky, and he resolutely got down to business. On May 9, 1942, Dmitry shot down three Ju-87s at once and rightfully took his place among the Soviet aces, bringing the number of victories to 6.

In that memorable battle, he himself was shot down and, having lost consciousness, descended by parachute. I came to my senses only after two days in the hospital. Doctors said that all this time he was fighting: his hands moved as if he was flying an airplane, and at times his muffled voice could be heard giving orders to attack. The concussion turned out to be very serious, it came to the point of issuing a medical opinion: to remove the young pilot from flying... forever. A normal person would have come to terms with this decision, but this obsessed man did it his own way: after spending about two months in hospitals and failing to get the flight ban lifted, he fled back to his unit.

He made it in time, the regiment received reinforcements, and Dmitry was able to choose a wingman for himself. He took a liking to a thin, short young man. It was former teacher chemistry and biology Ivan Babak. Dmitry got it right with his choice. On November 1, 1943, guard junior lieutenant Ivan Ilyich Babak was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. He fought almost until the end of the war, recording 35 personally shot down and 5 in a group of enemy aircraft. In February 1945, Guard Captain Ivan Babak was appointed commander of the air regiment. Fate turned out to be unkind to the hero. On March 16, 1945, during a combat mission, his plane came under anti-aircraft fire and the pilot was captured, from where he was released only after the Victory. Fortunately, he avoided the fate of many who returned from captivity and was again entrusted with command of the regiment. After demobilization, Babak returned to school, where he worked as a teacher and then as a school director.

After returning to the regiment, Dmitry Glinka literally the next day - July 13, 1942 - shot down a twin-engine German bomber Xe-111. The crew of this one of the best bombers in the world at that time consisted of five people. Shooting in all directions and not allowing anyone to get closer to him, he presented a rather difficult target. Therefore, the victory won by Dmitry was very significant.

Dmitry was one of the “old men”; through his example, many learned the most complex science of winning, and he generously shared his experience and knowledge with everyone. He chose the simplest call sign for himself, just two letters - “DB”, and everyone in the regiment knew that if in the air it sounds: “I am DB, I am DB”, it means that Dmitry Glinka is nearby, there will soon be another victory.

The regiment fought heavy, exhausting battles, and in mid-September, having lost 30 aircraft and 12 pilots, but having added 95 air victories to its combat account, a significant share of which was contributed by D. Glinka, who shot down 11 fascists, it was sent for reorganization and replenishment. All the pilots of the regiment needed this respite, but most of all Dmitry. Fatigue had accumulated from many combat missions and battles. In addition, the consequences of an untreated concussion were felt.

The regiment appeared at the front in March 1943, when a fierce battle was taking place in the skies over the Kuban. Having shot down two Me-109 and Ju-88 by the end of the month, Dmitry Glinka brought his combat tally to 15 victories. On April 24, 1943, Lieutenant Glinka Dmitry Borisovich was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Exactly four months passed, and the second Golden Star shone on his chest. On August 24, 1943, Dmitry, having added 14 downed enemy aircraft to his record and conducted 62 combat missions, was awarded the title of twice Hero of the Soviet Union.

And what was happening at the same time with his older brother, Boris Glinka. No matter how much he asked to go to the front, the school management in no way wanted to let the excellent instructor go. An accident helped or, as they say, providence helped.

In September 1942, the regiment in which Dmitry Glinka served was withdrawn to the rear, to the Caspian Sea. It was stationed at a training aviation base not far from Baku. There was an urgent need to replenish the flight personnel, which had been greatly reduced in battle, to give the pilots the opportunity to master new equipment, and in order to fly together, the reformed squadrons also needed time.

But most importantly, the extremely exhausted people needed to rest. Indeed, on those days when the weather allowed flights, the pilots spent almost the entire daylight hours in the sky. They descended to the ground only to refuel, replenish ammunition, and perform minor repairs. 5 or 6 sorties were not the limit. There is a known case when Dmitry rose into the air 9 times. He was incredibly strong and resilient, but everything comes to an end. Having difficulty reaching the bed, he collapsed on it and slept for 18 hours without a break. Doctors diagnosed him with severe fatigue and even recommended that he be suspended from flying for a week. But Dmitry would have betrayed himself if he had given in to the doctors. Having slept off, he again went to the sky.

Finally, the time came when it was possible, after theoretical studies or training flights, to calmly walk along the streets of the capital of Soviet Azerbaijan in the distant rear. During one of his walks along the embankment, Dmitry noticed a familiar figure in a flight jacket. Not trusting himself, he quietly called out:

Borya, is that you?

Dimka, how did you get here?

For retraining. What are you doing here?

I teach people like you,” and Boris nodded with envy at his younger brother’s chest, decorated with two Orders of the Red Banner and a medal.

Come with us.

They don't let go.

The brothers went to the hotel and talked all night, and in the morning they came to the regiment commander Ibragim Dzusov. It was he who helped solve a seemingly insurmountable problem. Boris was released to the front. When Dzusov was later asked how this was possible, he laughed:

Yes, the head of the school turned out to be a Caucasian, but it doesn’t happen that two Caucasians don’t agree. It happens more correctly, of course, but this is irreconcilable hostility for the rest of your life. And everyone wants to live happily ever after.

At that time, the famous battle over Kuban began. The Germans concentrated more than 1,000 aircraft there, while the Red Army had about 170 aircraft in the area. Air units and Soviet leadership began to move towards Kuban. Among them was the regiment in which the brothers served. Now our pilots were sitting at the controls of the Airacobras received under Lend-Lease from the USA.

The first battle in the skies of Kuban ended with a sensation. The fact that Dmitry shot down two Ju-88s did not surprise anyone, but the two fascists Me-109 and Ju-88 shot down by Boris amazed everyone. The first combat mission, the first meeting with a formidable enemy, and such success is unthinkable! It happened on March 10, 1943.

Boris quickly caught up with his brother. Having won his first victory a year later than Dmitry, he received the title of Hero of the Soviet Union exactly a month after Dmitry. On May 24, 1943 (again the cherished number 24!) he was awarded this high title, having shot down 10 enemy aircraft in the first two months of fighting.

The Battle of the Caucasus, of which the Kuban air battles were part, continued. Now it was necessary to break the notorious “Blue Line”, with this name it went down in history (in the Third Reich it was called “Gotenkopf”, literally translated as “Goth’s Head”), a powerful defensive fortification stretching between the Azov and Black Seas with a defense depth of 20− 25 km, and on the main direction - even 60 km. Up to six defensive lines, cutting-off positions, three lines in depth, pillboxes, bunkers, machine-gun platforms, gun trenches, a web of communication passages, and all this is covered by minefields and wire barriers (from 3 to 6 rows). It should be especially noted that if the attack in the north Soviet troops There were a lot of swamps, flood plains, and estuaries in the way, but in the south there were impenetrable mountains covered with forest.

And above all this there were continuous air battles for three months. On some days, up to 50 battles took place, in which up to a hundred aircraft took part on each side. A kind of continuous aerial leapfrog, accompanied by the annoying roar of engines and the fumes of exhaust gases. The tasks of our bomber aviation were clear. If the enemy’s ground troops are buried in the ground and infantry and tanks cannot move them from their place, then we need to help them do this from the sky. Deliver continuous blows to the enemy’s front line, iron it out, and do not let the fascists raise their heads. But German bombers and attack aircraft also had similar goals. Therefore, fighter jets came to the fore. They were the ones who were supposed to accompany the bombers, intercept enemy aircraft, and cover ground troops.

Both brothers distinguished themselves in battles over Kuban: Dmitry became the most effective pilot there, having shot down 18 enemy aircraft in a few weeks. Boris was not far behind him, having chalked up 14 victories. There were many battles, but everyone remembered one.

This happened on April 15, 1943. The intense battle, in which our fighters had to prevent the German “bombers” from reaching the front line, ended just fine. Diving from above and rushing through the dense formation of Junkers, Dmitry, with a short burst, shot down the leader of the flight of Messers accompanying about 60 Ju-88s. He was faced with another task - to tie up the lower escort group in battle. Another pair of us was supposed to start a fight from the top, and the rest of the squadron pilots were supposed to disperse the Junkers, forcing them to free themselves from the bomb load before reaching our positions.

Five Messers, angry at the impudent Russian, chased after him. Dmitry rushed upward, pulling German fighters with him. Masterfully operating the car, he deftly avoided the shells of German aircraft guns, carefully monitoring enemy aircraft. Having dragged the Germans to the maximum height, Dmitry abruptly changed the direction of flight and found himself on the tail of the slightly lagging German. Another well-aimed burst - and the German, somersaulting, rushed to the ground. A few seconds later, in the next attack, Dmitry shot down another Messer, but he himself did not have time to dodge the bursts of seriously angry enemies - he was set on fire and fell to the ground in front of his comrades.

Everyone returned to the unit except Dmitry Glinka. Everyone decided that he was dead. The regiment's pilots vowed to avenge the death of their comrade. They fought the most fiercely that day. 20 German planes did not return to their airfields. Boris especially distinguished himself. Just like younger brother, he shot down three fascist planes: one Ju-88 and two Me-109. What happened to Dmitry? His comrades saw his burning plane crash into a mountain spur, but it was far away, and no one noticed whether he managed to jump out with a parachute or not. There remained a ghostly hope that he made it in time.

A few days later, when Boris was on a flight, a tall, well-built young man in tattered clothes appeared at the airfield.

DB is back! - joyful cries of fellow soldiers were heard.

Almost at the same moment Boris’s plane landed. The meeting of the brothers was such that everyone who was at the airfield came running.

It turned out that Dmitry managed to fall out of the burning plane and pull the parachute ring. The unconscious pilot was picked up by those closely watching the battle. local residents. Carefully placing Dmitry on the silk cloth that saved his life, the mountaineers carried him to the nearest hospital. There the pilot came to his senses and, despite the doctors’ prohibitions, escaped to his unit a couple of days later.

And again it sounded in the air:

I am DB. I'm attacking.

And in response:

I'm BB. I understand you.

On April 24, 1943, Guard Captain Dmitry Borisovich Glinka was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. Exactly three months passed, and on July 24 he was awarded the title of twice Hero of the Soviet Union. What had to be done in these short months for such a tangible result to come?

It turns out that we didn’t have to do anything supernatural. It was simply necessary to fight honestly and very earnestly. To fight not anyhow, but according to science, developed by him himself. “The larger the enemy, the easier it is to beat him,” said Dmitry Glinka. He had remarkable strength and incredible endurance. Extremely adventurous, if he didn’t have to refuel the plane and replenish the ammunition, he would still be rushing through the skies, finding and attacking more and more new air targets.

His “Air Cobra” with tail number “21” was known to the entire front on which he fought, and it was constantly heard on the air: “I am the DB, I’m attacking, cover.” He flew reconnaissance and bombed enemy airfields, shot at concentrations of enemy troops and equipment, covered our units from enemy bombers and, in turn, accompanied our bombers, trying to prevent fascist fighters from approaching them. In general, he did what he was obliged to do as part of his military duty, but he did it with all his heart and with all his strength, while at the same time squeezing much more out of the technology than its creators had intended.

Many years later, one of his wingmen, the legendary Soviet ace, a participant in three wars (the Great Patriotic War, the war in Egypt and the war in Ethiopia), Colonel General of Aviation, Hero of the Soviet Union Grigory Ustinovich Dolnikov, recalled in his book of memoirs “The Steel Squadron is Flying”:

“...Tall, his strong-willed gaze from under short eyebrows gave his face a stern, even stern expression, and we, young people, were openly afraid of this gaze. A master of air combat, Dmitry shot very accurately from short distances, piloted with high overloads, most often without radio warning of his maneuver.”

And here’s what another former wingman, who also later became a Hero of the Soviet Union, commander of the “Pokryshkinsky” regiment, Ivan Ilyich Babak, recalled about him:

“He knew how to use the prevailing situation extremely effectively in any battle with the enemy, well organized interaction within the group... he was distinguished by the exceptional art of conducting battles on vertical lines.”

It is this art of fighting on verticals that I would like to talk a little about. Our pilots in the schools that they graduated from before the war and when it was already in full swing were taught to fly, and taught well. But how to conduct an air battle was explained to them in such a classical way that many did not have time to use this knowledge in practice; they were shot down earlier. The Germans developed special war tactics and taught them in their flight schools. Ours, those who managed to survive the first few battles, had to comprehend it in practice.

German fighters, as a rule, climbed higher into the sky and, having chosen a suitable target below, fell on it like a stone, shot it down and climbed up again.

After one such battle, Dmitry Glinka proposed dividing our pilots into several echelons. Some below are accompanied by bombers or attack aircraft, others higher up are tied up by fascist fighters, and still others attack the enemy from an even higher position. The regiment commander, having listened to the young pilot’s proposal, approved it. This is how the famous “Kuban whatnot” arose. In addition to the obvious superiority manifested in battle, this technique made it possible to confuse the enemy, since he did not know how many aircraft were opposing him.

Here brief description one of the battles carried out by Dmitry Glinka in the skies of Kuban. Our six, led by Glinka, attacked 60 Junkers, covered by 8 Messers, located above their bombers. Two groups of Soviet aircraft simultaneously attacked the Nazis. Glinka’s pair crashed into the Junkers formation and, spinning among them, opened devastating fire. The enemy panicked, dropped bombs randomly, and the Germans hurried back. Glinka and his wingman managed to shoot down three bombers. At the same time, the Soviet four, in a stubborn battle with fascist cover, were also able to defeat them, while two Messers were shot down and the rest retreated.

This is how the famous aircraft designer Alexander Sergeevich Yakovlev described this battle in his book “The Purpose of Life”:

“It’s hard to even mentally imagine the picture of this battle! After all, 68 enemy aircraft directed more than 150 barrels of their firing points against our fighters. You had to have insane courage (...) to rush into battle and win victory.”

The Germans, in response, began to clear the sky with large forces of fighters before the arrival of their bombers, trying to remove Soviet fighters from it before the start of the bombing. However, patrolling, echeloned in height, made it possible to successfully solve this problem. If there was a clear surplus of German fighters, it was always possible to call the duty group for help by radio.

A special mention should be made of “free hunting,” which our aces were sometimes allowed to do. It was at such moments that Dmitry Glinka could show his best qualities, necessary for a true air fighter: fantastic reaction, complete affinity with the aircraft, an incomprehensible sense of distance and amazing sniper accuracy.

This is how he himself assessed what qualities a real ace should have:

“A weak pilot spins in the car like a weather vane, intensely monitoring the instruments and the horizon. It doesn’t have the ease of flight, it doesn’t have that unity when you and the car are one. And this must be achieved.”

Dmitry turned out to be an excellent teacher, but in the best possible way He believed in upbringing by personal example. And he tirelessly shot down enemy planes, destroyed enemy tanks, vehicles, and batteries. He did not favor the infantry either, mercilessly destroying them in those seconds when he swiftly swept over the front line, pouring fire and lead all around.

For Dmitry, the Kuban battles were the best. With 20 victories, he became the most successful ace of that campaign.

The older brother tried to keep up with Dmitry, and sometimes even surpassed him. They were a wonderful couple, worthy of each other. It is thanks to such aces as the Glinka brothers, and many of their comrades in arms, in the skies of Kuban Soviet pilots achieved air superiority for the first time.

More and more often, the words “Glinka is in the air!” were heard in the headphones of German pilots. And the Germans did not care which brother it was; they knew that they would not get mercy from either one.

The Glinka brothers, Boris and Dmitry, fought in the same regiment and almost simultaneously became Heroes of the Soviet Union. They were real aces who gave no quarter to the enemy and always strived for victory. Real magicians in vertical battles, whose equals had yet to be found, they developed a unique style by which they could be unmistakably distinguished in the carousel of heavenly battle.

Both brothers flew into battle at the first opportunity, and it cannot be said that they were somehow charmed from enemy fire. Sometimes they got it pretty bad, and they even had to stay in hospitals, but each time, before they had time to recover, they returned to the sky, and again in their headphones they heard: “I am the DB, I’m attacking” or “I am the BB, I have entered the battle.”

Articles about the exploits they accomplished regularly appeared in the front-line press, and the central newspapers did not deprive the brave brothers of their attention. Some of their battles were covered in the press by war correspondents at that time. Here's one of them. It happened in stubborn battles on the Mius Front.

For the uninitiated, I’ll explain: “Mius Front” - under this name, a German fortified area in the Donbass on the western bank of the Mius River, created back in December 1941, entered the history of the Great Patriotic War. The most fierce battles took place at the height called “Saur-Mogila”. As a result of the Donbass offensive operation After the breakthrough of the German defense line in the area of the village of Kuibyshevo, the “Mius Front” was finally finished. The total losses of our army on the Mius Front amounted to more than 800 thousand people. Subsequently, a memorial complex was built at Saur-Mogila in memory of the feat Soviet soldiers who died both during the assault on this height and in the entire operation.

The air battle over the Mius Front is considered one of the key ones in 1943. One day, eight Soviet fighters, led by Dmitry Glinka, protected their front line from bombing. Two planes were sent across the front line. They were obliged to warn about the appearance of fascist bombers.

This is how Dmitry Glinka told a correspondent about this fight:

“We’re on patrol. From our guidance radio station, calling me with the initials of my name and patronymic, they report: “DB, you can’t see a damn thing - dust and smoke. See for yourself." But I wasn't worried. After all, there are a couple of our fighters behind the front line. The guys know their job and will let you know if anything happens. Literally a minute later there was a report from the leading pair: “DB, a large group of bombers is coming.” I led my group to approach the enemy. We attacked the bombers long before they approached the target, 20 kilometers from the front line. Shot down 5 enemy vehicles. We had no losses...”

And one more description of an air battle using a publication in a front-line newspaper. The ground warning service reported that enemy aircraft were approaching the front line. Our fighters, led by Dmitry Glinka, immediately took to the sky. The group is divided into two parts. One rises up, the other, in which the commander is located, flies towards the fascist bombers.

Here is his story:

“I hear a ground radio station: “Enemy fighters at an altitude of 3000 meters.” Any other time I would have gone up. But now there is no need to do this. I just conveyed the message I received to the top group. And now she is already fighting with enemy fighters. After 2 minutes the bombers I was waiting for appeared. We are also entering the battle. One after another, enemy planes, shrouded in smoke, fall to the ground. The formation of enemy vehicles was disrupted, not a single bomber reached the target...”

The elder brother, Boris Glinka, also showed courage and skill in the air. In June 1944, he was appointed commander of the 16th Guards Aviation Fighter Regiment, replacing G. Rechkalov in this post. However, less than a month later, on July 16, 1944, when Boris Glinka flew out on his next combat mission, he was shot down. The young wingman, whom Boris took as his partner for an internship, failed to protect him. Carried away by the battle, he allowed the German fighter to come within a minimum distance, and it literally shot down Glinka’s plane. Boris managed to get out of the falling plane, but in doing so he hit the stabilizer hard, seriously breaking his leg and collarbone. Long-term treatment in the hospital could not help him return to the front. The war was over for him. By that time, Boris had shot down 30 planes personally and 1 in the group.

After recovery, Boris Glinka did not leave the army. In 1952, he graduated from the Air Force Academy and began serving as a teacher at the Borisoglebsk Military Aviation School, and after the creation of the Cosmonaut Training Center he was transferred there, where he served almost until his death. Numerous wounds received during the war did not remain without consequences, and after a serious illness, Hero of the Soviet Union Guard Colonel Glinka Boris Borisovich died on May 11, 1967. He was then only 52 years old. One of the best Soviet aces was buried at the Grebenskoye cemetery in Star City, Moscow region.

Dmitry also suffered injuries, and some were received not in battle, but due to a tragic coincidence of circumstances. It was July 1944. There was nothing left to fly in the regiment. So five pilots, led by Dmitry Glinka, were sent to the rear for new aircraft. It was necessary to fly on a transport Li-2. When Glinka and his comrades arrived at the airfield, all the seats in the Li-2 were already taken. The pilots had to position themselves at the very rear of the car, where airplane covers lay on the floor. It saved their lives. During the flight, the plane entered low clouds, got caught on the top of the Kremenets Mountain and crashed. Only five fighter pilots survived, and even then, all of them were injured. to varying degrees gravity. Dmitry suffered the most. After several days of being unconscious, he had to spend another couple of months in the hospital.

After recovery, Dmitry Glinka continued to fight successfully. He scored his last 50th victory near Dresden on April 30, 1945, shooting down an Me-109. After the Victory he was left in the army. At first he was deputy commander of the 45th Fighter Aviation Regiment, but in 1946 he was sent by the command to study. After graduating from the Air Force Academy in 1951, he commanded the 315th and 530th IAP in the 54th Air Army. In January 1954, he was appointed deputy commander for flight training of the 149th, and in 1958, the 119th Fighter Aviation Division, stationed in the Odessa region.

On January 15, 1960, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted the Law on the next (third in a row) reduction Armed Forces per 1 million 200 thousand people. According to this Law, the division in which Dmitry Glinka served was reduced, and the 42-year-old twice Hero of the Soviet Union was forced into the reserve. But he could not live without heaven. At that time, much attention was paid in the country to the development civil aviation, that’s where he went.

These are the words the heroic pilot said in one of his interviews at that time:

“On a July morning in 1945, I was among those who threw enemy banners at the foot of the Mausoleum of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. I could retire, pick mushrooms, hunt, listen to my favorite music, and read books. But I can’t live without the sky, I can’t live without the helm.”

Dmitry Borisovich died on March 1, 1979. He was buried at the Kuntsevo memorial cemetery in the capital.

Dmitry Glinka has long been no longer among the living, but the Sukhoi Superjet 100 passenger aircraft with tail number RA-89046 and the proud name “Dmitry Glinka” regularly takes to the skies. And this is probably the best memory of the great fighter.