Lev Gumilyov's scientific discoveries. Biography of Lev Nikolaevich Gumilev

They say that nature rests on the children of geniuses. However, there are exceptions.

On October 1, 1912, a son, Lyovochka, was born to the poets Nikolai Gumilyov and Anna Akhmatova. Lev Nikolaevich Gumilev (1912 - 1992), who became a famous scientist, historian and geographer, the author of the theory of ethnogenesis.

It seems that neither mom nor dad needed a son. From 1912 to 1929, the boy lives with his grandmother, Anna Ivanovna Gumileva, first in Tsarskoe Selo, then in the Tver province, also in the village, but not in the Tsar's one, but in the family estate of Slepnevo. Later, my grandmother and her grandson moved to the city of Bezhetsk. In 1929, at the end of nine classes of school, Lev Gumilyov came to Leningrad and settled with his mother in the Fountain House. In 1930, he tried to enter the Pedagogical Institute, but failed. Summed up the biography - a noble child. Such people were admitted to higher educational institutions only after labor "reforging".

Labor "reforging" lasted 3 years. Lev Gumilyov works in various expeditions: in the geological - in the Baikal region, in the medical - in Central Asia, in the archaeological in the Crimea. Everything went to the good. In the Baikal region, he saw what Central Asia is, the cradle of the Turkic ethnos. In Tajikistan, he learned the Tajik language (in general, this is Persian, which will also be useful to him later). In Crimea, I got acquainted with the work of archaeologists.

In 1934, Lev Gumilev returned to Leningrad and, finally, entered the Leningrad State University at the Faculty of History. It would seem that the hardships are over. No, all the nasty things were just beginning.

After the murder of S.M. Kirov in December 1934, purges and arrests of the “noble element” began in Leningrad. L. Gumilyov was arrested in November 1935, but released on December 3.

However, on March 10, 1938, L.N. Gumilyov was arrested again, and this time in earnest. In September, he was recognized as an "enemy of the people" and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The verdict, to tell the truth, is divine. The next measure of punishment under the article under which L. Gumilyov was convicted was execution. Gumilyov is sent to the Belomorkanal.

But in 1939 the sentence was revised - oh, miracle! - towards the mitigation of punishment. LN Gumilyov is sentenced to 5 years in camps (however, taking into account the previous years of imprisonment in prison and in camps). L.N. Gumilyov was sent to Norilag.

Norilsk is one of the scariest places on the planet. It is located in the Arctic Circle. This means - gloomy, barely visible, twilight in winter, the sun that does not go beyond the horizon - in summer. Wild wind, knocking down at fifty degrees of frost. Even local residents, the Nganasans, migrate to the south in winter. With such a wind and a blizzard, you begin to sympathize equally with those who sit in the barracks and the watchmen standing on the towers.

In 1943 L. Gumilyov was released from prison and remained in Norilsk. Until October 1944 he worked as a technician in a local geophysical expedition, and then volunteered for the front. He fought in East Prussia and took Berlin.

In 1946, after demobilization, Lev Gumilyov graduated from the university and entered graduate school.

And again a witch hunt has been announced in Leningrad. This time, Anna Akhmatova is at gunpoint. In August 1946, she was expelled from the Writers' Union.

Fire on the mother, but goes to the son. In December 1947, L. Gumilyov was expelled from graduate school. They are expelled with a marvelous wording: "for the discrepancy between the philological training of the chosen specialty." There was indeed a discrepancy. It was required to know two languages, and Lev Gumilyov knew five, including Persian. However, the dissertation had already been written, and a year later, on December 28, 1948, Lev Gumilyov defended his dissertation on the topic “Political history of the first Turkic kaganate. VI-VIII centuries. n. e. ".

However, the candidate of historical sciences Lev Gumilyov greatly interferes with the Soviet power. On November 6, 1949, he was arrested for the fourth time. 10 years of forced labor camps was a trifle in those days.

Karaganda, Kemerovo, Omsk Oblast - stages of labor activity of a highly qualified historian. Such is the story ...

In 1956, as the anecdotes say, the era of late rehabilitation came. On May 11, Lev Gumilyov was found not guilty of all the crimes he had previously been charged with. The state even gave him a penny as a token of compensation for the unfairly selected years. Since December 1956, L.N. Gumilyov begins to work at the State Hermitage. And since 1960, his books have been published on the history of the nomadic peoples of Central Asia and, most importantly, on the theory of ethnogenesis that he developed.

It must be said that the history of nomadic peoples is a particularly difficult job for a historian. It is difficult to find traces of the material culture of the tribes who moved across the great steppe expanses behind their herds. Only burial mounds could please with rare finds. And even eyewitness accounts. Suddenly frantic nomads appeared, everything that was built was captured, burned, people were taken into slavery. Where, for what reason, did these or those tribes suddenly gather in hordes and roll from east to west, destroying everything in their path? Neither Marxist history, nor any other history, has provided an explanation for the question of how ethnic groups appear - large groups of people united by some common features, and not always objective ones.

According to the theory of L.N. Gumilyov, ethnos is not only a social community. Ethnic groups are tied to the geography of a particular region, to its climate and its nature. At some point, under the influence of natural, including cosmic, forces, a group of passionaries appears within the framework of an already existing ethnos. Passionate personalities, if you do not fence in scientific terms, these are personalities "shifted" to change their lives and the lives of those around them, to change the environment, to rush somewhere to the ends of the earth for elusive happiness. If there are enough passionaries, they gather in groups and, united by some common goal, create a new ethnos. In a sense, this is reminiscent of the locust phenomenon known to biologists. Ordinary harmless green grasshoppers suddenly, under the influence of natural conditions (many biologists believe that cosmic factors too) unite and become a natural disaster, destroying everything in their path.

With the help of his theory of ethnogenesis, LN Gumilev tried to explain the laws of the historical process. His views often contradicted the already widespread views in historical science. For example, according to L.N. Gumilyov, the relationship between the Mongol nomads and Russia was much less dramatic than it is still commonly believed. In fact, there was no Mongol-Tatar yoke. This concept was invented almost in the 18th century. The steppe nomads, according to the views of L.N. Gumilyov, were not savages at all, but rather highly organized ethnic groups. Not surprisingly, the memory of the Russian historian is honored both in Kazakhstan and in Tatarstan. He himself said about himself: "I, a Russian person, have been protecting the Tatars from slander all my life ..."

Gumilyov's theory of ethnogenesis and his other theories evoke various assessments, from enthusiastic to destructive. In any case, his books deserve attention and thoughtful reading. They are written in an interesting and lively way, so reading will not be boring. In any case, this reading will be useful, because it will make you take a fresh look at the seemingly unshakable truths in the history of Russia. And understand that there are no unshakable truths here.

October 1, 2012 marks the hundredth anniversary of the birth of the Russian scientist, historian-ethnologist, poet, translator Lev Nikolayevich Gumilyov.

Russian scientist, historian-ethnologist, poet, translator Lev Nikolayevich Gumilyov was born on October 1 (September 18, O.S.) 1912 in St. Petersburg in the family of Russian poets Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilyov and Anna Andreevna Akhmatova.

From 1912 to 1916, Lev Gumilyov lived with his grandmother Anna Ivanovna Gumileva in Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg, from 1916 to 1918 - in the family estate of Slepnevo and in Bezhetsk (Tver region).

In August 1921, on charges of participating in a counter-revolutionary conspiracy, his father Nikolai Gumilyov was arrested and shot.

In 1929, Lev Gumilev graduated from high school in Bezhetsk and moved to his mother in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg).

In 1929-1930, Gumilyov studied at the unified labor school No. 67 in Leningrad and lived with his mother in the Fountain House. His first attempt to enter the Pedagogical Institute failed: noble children were not taken to higher educational institutions.

In November-December 1930 he worked as a laborer in the Service of the Railroad and Current.

In the spring of 1931 he was hired as a collector in the Geological Committee (Geolkom), worked in the Pribaikalskaya geological expedition.

In 1932 he worked as a laboratory assistant on an expedition to Central Asia, then - as a malaria scout at the Dangara state farm, taught the Tajik language. Upon returning to Leningrad, he got a job as a collector at the Central Scientific Research Geological Prospecting Institute of Non-Ferrous and Precious Metals (TsNIGRI).

In 1933, Lev Gumilyov was a scientific and technical employee of the Geological Institute of the Academy of Sciences (GINAN), worked in the Crimea as part of several expeditions.

In December 1933, Gumilyov was arrested, no charges were filed.

In 1934 he entered the Leningrad State University (LSU) at the restored history faculty. In 1934-1936 he worked as part of several archaeological expeditions.

On November 23, 1934, he was arrested along with several students. On December 3, 1934, after a letter from Anna Akhmatova to Joseph Stalin, everyone was released.

On March 10, 1938, Lev Gumilyov was arrested again, on September 28, 1938, a military tribunal court sentenced him to ten years of imprisonment with disqualification for four years and confiscation of property. To serve his term, he was sent to Medvezhyegorsk to build the Belomorkanal.

In 1939, as a result of a review of the case, the sentence was changed: five years in the camps (including imprisonment and work on the construction of the White Sea Canal). Gumilyov was sent to a forced labor camp in Norilsk.

From October 1939 to March 1943, he worked in Norilsk, mainly at the mine.

On March 10, 1943, at the end of his term, he was released from prison and left in a free settlement.

From March 1943 to October 1944 he worked as a geotechnical engineer in a geophysical expedition on Lake Khantayskoye and near Turukhansk in the Krasnoyarsk Territory.

In October 1944, Lev Gumilev volunteered for the front, took part in the battles in East Prussia and during the capture of Berlin. He was awarded medals "For the capture of Berlin" and "For the victory over Germany."

In October 1945 he was demobilized, returned to Leningrad and recovered at the university.

In 1946, Gumilev graduated from the university and entered the graduate school of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences (IVAN).

After Anna Akhmatova was expelled from the Writers' Union in 1946, in December 1947, Lev Gumilyov was expelled from graduate school with the wording: "for inconsistency in the philological training of the chosen specialty", although his thesis had already been written, the candidate exams were passed.

From February to May 1948 he worked as a librarian at the Psychotherapeutic Clinic. MI Balinsky, from May to November was a researcher of the Gorno-Altai expedition, took part in the excavation of one of the stone mounds in the Pazyryk valley in Altai.

On December 28, 1948 he defended his Ph.D. thesis on the topic "The political history of the first Turkic kaganate. VI-VIII centuries AD."

In 1949, he worked as a senior researcher at the State Museum of Ethnography (GME), participated in the work of the Sarkel archaeological expedition.

In the same year he was admitted to the number of full members of the Geographical Society at the USSR Academy of Sciences.

On November 6, 1949, Lev Gumilyov was arrested again and sentenced to ten years in forced labor camps. From 1949 to 1956 he served time in camps in the village of Churbay-Nura near Karaganda, in the village of Olzheras and near Omsk. During that period he was ill a lot, but continued to work on a book on the history of Central Asia.

In December of the same year he was hired by the State Hermitage at the Central Scientific Library.

From 1957 to 1962 he headed the work of the Astrakhan archaeological expedition of the Hermitage.

In 1959, Gumilev headed the section of ethnography at the Leningrad branch of the All-Union Geographical Society (VGO).

In November 1961, Gumilyov defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic "Ancient Turks".

In 1962 he went to work at the Research Geographical and Economic Institute of Leningrad State University (NIGEI) at the Faculty of Geography.

Anna Akhmatova died on March 5, 1966. Lev Gumilyov achieved a funeral service for his mother according to the church rite, a trial began on Akhmatova's inheritance.

In the same year, his book "The Discovery of Khazaria" was published, Gumilyov met in Moscow with the artist Natalia Simonovskaya, who later became his wife.

In 1970, Gumilyov's articles on history, historical geography, nomadism and ethnography were published; continuation of the series of articles "Landscape and Ethnos", the book "Searches for a Fictional Kingdom" was published, which aroused great interest among readers, and at the same time a surge of hostile criticism.

In 1971, Lev Gumilyov's publications and speeches became known abroad, his articles were published in foreign magazines. In 1972 in Warsaw (Poland) the book "Ancient Turks" was published, and in Turin (Italy) - "Hunnu". In 1973, his book "The Search for a Fictional Kingdom" was published in Poland.

In 1974, a harsh critical article was published in the journal Voprosy istorii SSSR (by Viktor Kozlov, Doctor of Historical Sciences), after which Gumilyov's articles and books were no longer published. Gumilyov's answer to the criticism has not been published.

In May of the same year, Gumilyov defended his second doctoral dissertation in geography - "Ethnogenesis and the Earth's biosphere".

In 1976, the Higher Attestation Commission (VAK) refused to award Lev Gumilyov the degree of Doctor of Geographical Sciences. A period of "silence" began: Gumilyov's works were not published, articles were returned from editorial offices. However, his lectures became widely known, some articles were published in "nonscientific" journals: during these years he began cooperation with the journal "Decorative Art".

From 1981 to 1986, Gumilyov's publications were banned, the Siberian branch of the Academy of Sciences refused to publish the book "Ethnogenesis and the Biosphere of the Earth." At the same time, he continued to be invited to lecture to scientific communities in various cities, as well as to consult at film studios, radio and television.

In 1987, Gumilyov sent a letter to the Department of Science and Educational Institutions of the Central Committee of the CPSU, after which the ban on publications was lifted.

In 1988, 22 publications of the scientist were published. One of the most significant publications is "Biography of Scientific Theory, or Auto Necrology" in the Znamya magazine and in two issues of the Neva magazine under the title "Apocryphal Dialogue".

In 1989, the publishing house of Leningrad State University published the book "Ethnogenesis and the Biosphere of the Earth" (which became one of the main works of Gumilyov), in Baku in the magazine "Khazar" a historical and psychological study "Black Legend" was published.

In the fall of the same year, Gumilyov suffered a stroke.

In 1990, the monographs "Ethnogenesis and Biosphere of the Earth", "Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe" (she was subsequently awarded the A.V. Lunacharsky Prize) and "Geography of Ethnos in the Historical Period" - a course of lectures on ethnology (original title : "End and start again").

On December 29, 1990, he was elected a full member of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences.

In 1991, the publication of his books and articles continued, and series of lectures were organized on radio and television.

On June 15, 1992, after a serious and prolonged illness, Lev Gumilyov died and was buried at the Nikolskoye cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra in St. Petersburg.

On October 1, 1992, Gumilyov was awarded the prize. X. 3. Tagiyeva (Azerbaijan) (posthumously) for the book "Millennium around the Caspian Sea".

In December of the same year, his last book, From Russia to Russia, was published, a signal copy of which he managed to see in the hospital.

Gumilyov is the author of over 200 articles and 12 monographs, lectures on ethnology, poems, dramas, stories and poetic translations. His doctrine of humanity and ethnic groups as biosocial categories is one of the most daring theories about the laws in the historical development of mankind and still causes acute controversy.

In 1995 Lev Gumilyov's book "From Rus to Russia" received the Vekhi award, and in 1996 it was recommended as an optional history textbook for grades 8-11 of secondary school. In the same year, the book "Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe" was recognized by the Book Chamber as the best book of the year.

In 2003, in the center of the city of Bezhetsk, a monument to Lev Gumilyov, Nikolai Gumilyov and Anna Akhmatova was unveiled by sculptor Andrei Kovalchuk.

In August 2005, a monument to Lev Gumilyov was opened in Kazan.

In 1996 in Astana (Kazakhstan) one of the leading universities of the country, the L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, was named after Gumilyov.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from RIA Novosti and open sources

The parents' marriage actually disintegrated in 1914, his grandmother was engaged in upbringing, in whose estate near Bezhetsk (Tver region) the child spent his childhood. When the boy was 9 years old, his father was accused of participating in a White Guard conspiracy and shot. Later, this fact more than once served as a pretext for political accusations of the "son of an enemy of the people."

In 1926 he moved to live from Bezhetsk to Leningrad, to his mother. In 1930 he was denied admission to the Pedagogical Institute. Herzen due to his non-proletarian origin and lack of a work background. For four years he had to prove his right to education, working as a laborer, collector, laboratory assistant. In 1934 he entered the history department of Leningrad University, in 1935 he was arrested for the first time. Gumilyov was quickly released, but expelled from the university. For the next two years, he continued his education on his own, studying the history of the ancient Turks and oriental languages. In 1937 he was reinstated at the Faculty of History, but a year later he was arrested again. After a long investigation, he was sentenced to 5 years of exile in Norilsk. After the expiration of his term, he could not leave the North and worked in the expedition of the Norilsk plant. In 1944 he volunteered for the front and as part of the First Belorussian Front and reached Berlin.

Immediately after demobilization, Lev Nikolayevich graduated from the history faculty of Leningrad University as an external student and entered the postgraduate course of the Institute of Oriental Studies. Taught by bitter previous experience, Gumilyov feared that he would not be allowed to stay free for a long time, so he passed all the exams and prepared his thesis in a short time. However, the young scientist did not have time to defend her - in 1947, as the son of the disgraced poetess, he was expelled from graduate school. His scientific biography was interrupted again, Gumilyov worked as a librarian at a psychiatric hospital, and then as a research assistant for the Gorno-Altai expedition. Finally, in 1948 he managed to defend his Ph.D. thesis on the history of the Turkic Khaganate. For less than a year he worked as a senior researcher at the Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR until he was arrested again. He spent a new 7-year term in camps near Karaganda and near Omsk. During this time, he wrote two scientific monographs - Huns and Ancient Turks.

In 1956 he returned to Leningrad, got a job at the Hermitage. In 1960 the book was published Hunnu, which has caused diametrically opposite reviews - from devastating to moderately laudatory. Doctoral dissertation Ancient Turks, written by him in the camp, Gumilyov defended in 1961, and in 1963 became a senior researcher at the Institute of Geography at Leningrad University, where he worked until the end of his life. In 1960, he began to give lectures on ethnology at the university, which were very popular among students. "Political unreliability" ceased to interfere with his scientific career, the number of published works increased dramatically. However, his second doctoral dissertation Ethnogenesis and the Earth's biosphere, defended in 1974, was approved by the Higher Attestation Commission with a long delay - not because of the author's “unreliability”, but because of the “unreliability” of his concept.

Although many of the scientist's views were sharply criticized by his colleagues, they were increasingly popular among the Soviet intelligentsia. This was facilitated not only by the originality of his ideas, but also by the amazing literary fascination of their presentation. In the 1980s, Gumilyov became one of the most widely read Soviet scientists, his works were published in large editions. Gumilyov finally got the opportunity to freely express his views. Constant tension, work on the verge of strength could not last long. In 1990 he suffered a stroke, but did not stop his scientific activities. June 15, 1992 Lev Nikolayevich Gumilyov died, he was buried at the Nikolskoye cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

Historians value Gumilyov primarily as a Turkologist who made a great contribution to the study of the history of the nomadic peoples of Eurasia. He protested against the widespread myth that nomadic peoples played exclusively the role of robbers and destroyers in history. He considered the relationship of Ancient Rus and the steppe peoples (including the Golden Horde) as a complex symbiosis, from which each nation gained something. This approach contradicted the patriotic tradition, according to which the Mongol-Tatars were allegedly always the irreconcilable enemies of the Russian lands.

Gumilyov's merit is his attention to historical climatology. Studying the "great migrations" of nomadic peoples, the scientist explained them by fluctuations in climatic conditions - the degree of moisture and average temperatures. In Soviet historical science, such an explanation of major historical events not by social, but by natural reasons seemed dubious, gravitating towards "geographical determinism."

After the collapse of Soviet ideological dogmas, many of Gumilyov's ideas were openly accepted by the Russian scientific community. In particular, there was school of Socio-Natural History (its leader is E.S. Kulpin), whose supporters develop Gumilyov's concept of the strong influence of the climatic environment and its changes on the development of pre-bourgeois societies.

Among the “general public,” however, Gumilyov is known not so much as a nomadist and climatologist, as as the creator of an original theory of the formation and development of ethnic groups.

According to Gumilev's theory of ethnogenesis, ethnos is not a social phenomenon, but an element of the bioorganic world of the planet (the Earth's biosphere). Its development depends on the flow of energy from space. Under the influence of very rare and short-term cosmic radiation (there were only 9 of them in the entire history of Eurasia), a gene mutation (passionary impulse) occurs. As a result, people begin to absorb much more energy than they need for normal life. Excess energy splashes out in excessive human activity, in passionarity. Under the influence of extremely energetic people, passionaries, there is the development or conquest of new territories, the creation of new religions or scientific theories. The presence of a large number of passionaries in one territory, favorable for their reproduction, leads to the formation of a new ethnic group. The energy received by passionate parents is partly transferred to their children; in addition, passionaries form special stereotypes of behavior that remain in effect for a very long time.

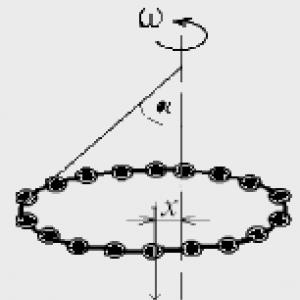

Developing, the ethnos passes, according to L.N. Gumilyov, six phases (Fig.):

1) lifting phase: characterized by a sharp increase in the number of passionaries, the growth of all types of activities, the struggle with neighbors for "their place in the sun." The leading imperative during this period is “Be who you should be”. This phase lasts approximately 300 years;

2) akmatic phase: passionate tension is the highest, and passionaries strive for maximum self-expression. A state of overheating often occurs - excess passionary energy is spent on internal conflicts. Social imperative - "Be yourself", phase duration approximately 300 years;

3) break - the number of passionaries is sharply reduced with a simultaneous increase in the passive part of the population (sub-passionaries). The dominant imperative is "We are tired of the greats!" This phase lasts about 200 years. It was at this stage of development, according to Gumilev, that Russia was at the end of the 20th century;

4) inertial phase: voltage continues to fall, but not abruptly, but smoothly. Ethnicity is going through a period of peaceful development, there is a strengthening of state power and social institutions. The imperative of this time period is "Be like me." Phase duration - 300 years;

5) obscuration - passionary tension returns to its original level. The ethnic group is dominated by sub-passionaries, who are gradually corrupting society: corruption is legalized, crime is spreading, the army is losing its combat capability. The imperative “Be like us” condemns any person who has retained a sense of duty, diligence and conscience. This ethnic twilight lasts 300 years.

6) memorial phase - from the former greatness only memories remain - "Remember how wonderful it was!" After the complete oblivion of the traditions of the past occurs, the cycle of development of the ethnos is completely completed. This last phase lasts 300 years.

In the process of ethnogenesis, interaction of various ethnic groups takes place. To characterize the possible results of such interaction, Gumilev introduces the concept of "ethnic field". He argues that ethnic fields, like other types of fields, have a certain rhythm of oscillation. The interaction of various ethnic fields gives rise to the phenomenon of complementarity - a subconscious feeling of ethnic closeness or alienation. Thus, there are compatible and incompatible ethnic groups.

Based on these considerations, Gumilev identified four different options for ethnic contacts:

2) ksenia - neutral coexistence of ethnic groups in one region, in which they will preserve their identity, without entering into conflicts and not participating in the division of labor (this was the case during the Russian colonization of Siberia);

3) symbiosis - mutually beneficial coexistence of ethnic systems in one region, in which different ethnic groups preserve their identity (this was the case in the Golden Horde until it converted to Islam);

4) merger representatives of different ethnic groups into a new ethnic community (this can only happen under the influence of a passionary impulse).

Gumilyov's concept leads to the idea of \u200b\u200bthe need to carefully monitor the processes of communication between representatives of different ethnic groups to prevent "unwanted" contacts.

In the last years of the existence of the USSR, when Gumilyov's doctrine of ethnogenesis first became an object of public discussion, a paradoxical atmosphere developed around it. To people far from professional social science, the theory of passionarity seemed truly scientific - innovative, awakening the imagination, having great practical and ideological significance. On the contrary, in the professional environment, the theory of ethnogenesis was considered at best dubious ("chain of hypotheses"), and at worst - parascientific, methodologically close to the "new chronology" of AT Fomenko.

All scientists noted that despite the global nature of the theory and its seeming solidity (Gumilev stated that his theory is the result of generalizing the history of more than 40 ethnic groups), there are a lot of assumptions in it that have not been supported by factual data. There is absolutely no evidence that some kind of radiation comes from space, the effects of which have been noticeable for more than a thousand years. There are no more or less solid criteria by which you can distinguish a passionate from a sub-passionary. Many ethnoses of the planet "live" much longer than the period prescribed by Gumilev's theory. To explain these "long-livers", Gumilev had, in particular, to assert that there is no single four-thousand-year history of the Chinese ethnos, but there is a history of several independent ethnic groups, successively replacing each other in China. Science still does not know any "ethnic field". In the works of Gumilyov on the history of ethnogenesis, claiming to generalize the entire ethnic history, experts find many factual errors and false interpretations. Finally, scientists consider Gumilyov's passionate theory to be potentially socially dangerous. Many critics regard the rationale for the prohibition of marriages between representatives of "incompatible" ethnic groups as racism. In addition, the theory of ethnogenesis justifies interethnic conflicts, which, according to Gumilev, are natural and inevitable in the process of the birth of a new ethnos.

After the death of Gumilyov, the controversy around the theory of passionarity basically stopped. The very concept of "passionarity" has entered the broad lexicon as a synonym for "charisma". However, the idea that ethnic groups are similar to living organisms has remained outside both science and mass consciousness. LN Gumilyov's works continue to be reprinted in large editions, but they are considered more as a kind of scientific journalism than scientific works in the proper sense of the word.

Major works: Collected Works, vols. 1-3. M., 1991; Discovery of Khazaria... M., Iris-press, 2004; Ethnogenesis and the Earth's biosphere... L., Gidrometeoizdat, 1990; Ethnosphere: History of people and history of nature... M., Ekopros, 1993; From Rus to Russia: Essays on Ethnic History... M., Ekopros, 1994; In search of a fictional kingdom... SPb, Abris, 1994

Natalia Latova

Biography of Lev Gumilyov

Lev Nikolaevich Gumilyov (October 1, 1912 - June 15, 1992) - Soviet and Russian scientist, historian-ethnologist, doctor of historical and geographical sciences, poet, translator from Persian. The founder passionary theory of ethnogenesis.

Born in Tsarskoe Selo on October 1, 1912. The son of poets Nikolai Gumilyov and Anna Akhmatova (see pedigree),. As a child, he was brought up by his grandmother on the Slepnevo estate of the Bezhetsk district of the Tver province.

From 1917 to 1929 he lived in Bezhetsk. Since 1930 in Leningrad. In 1930-1934 he worked on expeditions in the Sayan Mountains, the Pamirs and the Crimea. Since 1934 he began to study at the Faculty of History of Leningrad University. In 1935 he was expelled from the university and arrested, but after a while he was released. In 1937 he was restored to Leningrad State University.

In March 1938, he was arrested again as a student at Leningrad State University and sentenced to five years. He was in the same case with two other students of Leningrad State University - Nikolai Erekhovich and Theodor Shumovsky. He served his term in Norillag, working as a geological technician in a copper-nickel mine, after serving his term he was left in Norilsk without the right to leave. In the fall of 1944, he voluntarily entered the Soviet Army, fought as a private in the 1386 anti-aircraft artillery regiment (zenap), which was part of the 31 anti-aircraft artillery division (zenad) on the First Belorussian Front, ending the war in Berlin.

In 1945 he was demobilized, reinstated at Leningrad State University, from which he graduated in early 1946 and entered the graduate school of the Leningrad branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences, from where he was expelled with the motivation "due to the inconsistency of philological training in the chosen specialty."

On December 28, 1948, he defended his Ph.D. thesis at Leningrad State University and was accepted as a research fellow at the Museum of Ethnography of the Peoples of the USSR.

Memorial plaque on the house where L.N. Gumilyov lived (St. Petersburg, Kolomenskaya st., 1)

On November 7, 1949, he was arrested, sentenced by a special meeting to 10 years, which he served first in a special purpose camp in Sherubai-Nura near Karaganda, then in a camp near Mezhdurechensk in the Kemerovo region, in Sayan. May 11, 1956 rehabilitated due to lack of corpus delicti.

From 1956 he worked as a librarian at the Hermitage. In 1961 he defended his doctoral dissertation in history ("Ancient Turks"), and in 1974 - his doctoral dissertation in geography ("Ethnogenesis and the biosphere of the Earth"). On May 21, 1976, he was refused the award of the second degree of Doctor of Geography. Prior to retirement in 1986, he worked at the Research Institute of Geography at Leningrad State University.

He died on June 15, 1992 in St. Petersburg. Service in the Church of the Resurrection of Christ at the Warsaw station. He was buried at the Nikolskoe cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra.

In August 2005, a monument to Lev Gumilyov was erected in Kazan "in connection with the days of St. Petersburg and the celebration of the millennium of the city of Kazan".

On the personal initiative of the President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev in 1996, in the Kazakh capital Astana, one of the leading [source not specified 57 days] universities of the country, the L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, was named after Gumilyov. In 2002, within the walls of the university, a study-museum of L.N. Gumilyov was created.

The main works of L.N. Gumilyov

* History of the Hunnu people (1960)

* Discovery of Khazaria (1966)

* Ancient Turks (1967)

* Search for a fictional kingdom (1970)

* Hunnu in China (1974)

* Ethnogenesis and the Earth's Biosphere (1979)

* Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe (1989)

* Millennium around the Caspian Sea (1990)

* From Russia to Russia (1992)

* End and start again (1992)

* Black legend

* Synchronization. Experience in describing historical time

On the son of two amazingly talented poets of the past century, contrary to the postulate, nature did not rest. Despite 4 arrests and 14 years stolen by Stalin's camps, Lev Gumilyov left a bright mark on Russian culture and science. The philosopher, historian, geographer, archaeologist and orientalist, who put forward the famous theory of passionarity, bequeathed to the descendants a huge scientific heritage. He also composed poetry and poems, knowing six languages, translated several hundred other people's works.

Childhood and youth

The only son was born in the fall of 1912 on Vasilievsky Island, in the Empress's maternity hospital. The parents brought the baby to Tsarskoe Selo and was soon baptized in the Catherine Cathedral.

From the first days of his life, the son of two poets was in the care of the grandmother, mother of Nikolai Gumilyov. The child did not change the usual course of life of the parents, they easily entrusted the upbringing and all the cares for the boy to Anna Ivanovna Gumileva. Later, Lev Nikolayevich wrote that he hardly saw his mother and father in childhood, they were replaced by their grandmother.

Until the age of 5, the boy grew up in Slepnevo, his grandmother's estate, located in the Bezhetsk district of the Tver province. But in the revolutionary 1917, Gumilyov, fearing a peasant pogrom, left the family nest. Taking the library and some of the furniture, the woman with her grandson moved to Bezhetsk.

In 1918, the parents divorced. In the summer of the same year, Anna Ivanovna and Levushka moved to their son in Petrograd. For a year the boy talked with his father, accompanied Nikolai Stepanovich on literary affairs, and visited his mother. The parents soon after parting formed new families: Gumilev married Anna Engelhardt, in 1919 their daughter Elena was born. Akhmatova lived with the Assyriologist Vladimir Shileiko.

In the summer of 1919, the grandmother with her new daughter-in-law and children left for Bezhetsk. Nikolai Gumilyov occasionally visited his family. In 1921, Leo learned about the death of his father.

Lev Gumilyov's youth passed in Bezhetsk. Until the age of 17, he changed 3 schools. The boy did not develop relationships with his peers. According to the recollections of classmates, Leva kept himself apart. The pioneers and the Komsomol bypassed him, which is not surprising: in the first school, the "son of an alien class element" was left without textbooks, which were supposed to be for students.

The grandmother transferred her grandson to the second school, the railway, where Anna Sverchkova, a friend and a kind angel of the family, taught. Lev Gumilyov became friends with the teacher of literature Alexander Pereslegin, with whom he corresponded until his death.

In the third school, which was called the 1st Soviet, Gumilyov's literary abilities were revealed. The young man wrote articles and stories in the school newspaper, having received an award for one of them. Lev became a regular visitor to the city library, where he made literary reports. During these years, the creative biography of the Petersburger began, the first "exotic" poems appeared, in which the young man imitated his father.

Mom visited her son in Bezhetsk twice: in 1921, at Christmas, and 4 years later, in the summer. Every month she sent 25 rubles to help the family survive, but she harshly suppressed her son's poetic experiments.

After graduating from school in 1930, Lev came to Leningrad, to his mother, who at that time lived with Nikolai Punin. In the city on the Neva, the young man re-graduated from the final class and prepared for admission to the Herzen Institute. But Gumilyov's application was not accepted due to his noble origin.

Stepfather Nikolai Punin arranged for Gumilyov to be a laborer at the plant. From there, Lev went to the tram depot and registered at the labor exchange, from where he was sent to courses where geological expeditions were prepared. During the years of industrialization, expeditions were organized in huge numbers, due to a lack of staff, their origin was not looked at. So Lev Gumilyov in 1931 went on a trip to the Baikal region for the first time.

Heritage

According to biographers, Lev Gumilyov visited expeditions 21 times. While traveling, he earned money and felt independent, not dependent on his mother and Punin, with whom he had an uneasy relationship.

In 1932, Lev embarked on an 11-month expedition to Tajikistan. After a conflict with the head of the expedition (Gumilyov was accused of violating discipline - he took up studying amphibians during off-hours) he got a job at a state farm: by the standards of the 1930s, they paid well and fed here. Communicating with farmers, Lev Gumilyov learned the Tajik language.

After returning home in 1933, he undertook to translate the poetry of the authors of the Union republics, which brought him a modest income. In December of the same year, the writer was arrested for the first time, having kept him in custody for 9 days, but was not interrogated or charged.

In 1935, the son of two classics hated by the authorities entered the university of the northern capital, choosing the Faculty of History. The teaching staff of the university was full of masters: the Egyptologist Vasily Struve, the connoisseur of antiquity Solomon Lurie, the Sinologist Nikolai Kyuner, whom the student soon called a mentor and teacher, worked at Leningrad State University.

Gumilyov turned out to be head and shoulders above his fellow students and aroused admiration among teachers for his deep knowledge and erudition. But the authorities did not want to leave the son of the executed "enemy of the people" and the poetess, who did not want to glorify the Soviet system, at will for a long time. In the same 1935 he was arrested for the second time. Anna Akhmatova turned to, asking to release the most dear people (at the same time Punin was taken away with Gumilev).

Both were released at Stalin's demand, but Lev was expelled from the university. For the young man, the expulsion was a disaster: the stipend and bread allowance amounted to 120 rubles - a considerable amount at that time, which allowed him to rent an apartment and not go hungry. In the summer of 1936, Leo went on an expedition across the Don, to excavate a Khazar settlement. In October, to the great joy of the student, he was reinstated at the university.

The happiness did not last long: in March 1938, Lev Gumilyov was arrested for the third time, giving him 5 years in the Norilsk camps. In the camp, the historian continued to write his dissertation, but could not complete it without sources. But Gumilev was lucky with his social circle: among the prisoners there was the flower of the intelligentsia.

In 1944 he asked to go to the front. After two months of study, he ended up in a reserve anti-aircraft regiment. Demobilized, he returned to the city on the Neva and graduated from the history department. In the late 1940s, he defended himself, but never received his Ph.D. In 1949, Gumilyov was sentenced to 10 years in labor camps, borrowing charges from the previous case. The historian served his punishment in Kazakhstan and Siberia.

The release and rehabilitation took place in 1956. After 6 years of work in the Hermitage, Lev Gumilyov was hired by the Research Institute at the Faculty of Geography of Leningrad State University, where he worked until 1987. From here he retired. In 1961, the scientist defended his doctoral dissertation in history, and in 1974 - in geography (the scientific degree was not approved by the Higher Attestation Commission).

In the 1960s, Gumilev undertook to embody on paper the passionate theory of ethnogenesis, meaningful in the conclusion, with the goal of explaining the cyclical nature of history. Distinguished colleagues criticized the theory, calling it pseudoscientific.

The majority of historians of that time were not convinced by the main work of Lev Gumilyov, entitled "Ethnogenesis and the Biosphere of the Earth." The researcher was of the opinion that the Russians are the descendants of the Tatars who were baptized, and Russia is a continuation of the Horde. Thus, Russia is inhabited by a Russian-Turkic-Mongolian brotherhood, Eurasian in origin. This is what the popular book of the writer "From Russia to Russia" is about. The same theme is developed in the monograph “Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe”.

Lev Gumilyov's critics, respecting the researcher's innovative views and vast knowledge, called him a “conventional historian”. But the disciples idolized Lev Nikolaevich and considered him a scientist, he found talented followers.

In the last years of his life, Gumilyov published poetry, and his contemporaries noticed that his son's poetry was not inferior in artistic power to the poetry of his parents-classics. But part of the poetic heritage was lost, and Lev Gumilyov did not manage to publish the surviving works. The nature of the poetic style lies in the definition that the poet gave himself: "the last son of the Silver Age."

Personal life

A creative and amorous man, Gumilev was captured by female charms many times. Friends, students and lovers came to the Leningrad communal apartment where he lived.

In the late autumn of 1936, Lev Gumilev met the Mongolian Ochiryn Namsrajav. On a young graduate student, 24-year-old Leo, an erudite with the manners of an aristocrat, made an indelible impression. After classes, the couple walked along the University Embankment, talked about history, archeology. The romance lasted until his arrest in 1938.

With the second woman, Natalya Varbanets, nicknamed the Bird, Gumilyov also met in the library in 1946. But the beauty loved her patron, the married medieval historian Vladimir Lyublinsky.

In 1949, when the writer and scientist was once again taken to the camp, Natalia and Lev corresponded. There are 60 love letters written by Gumilyov to the employee of the State Public Library Varbanets. In the writer's museum there are also drawings of the Bird, which she sent to the camp. After his return, Lev Gumilyov parted with Natalia, whose idol was Lublinsky.

In the mid-1950s, Lev Nikolayevich had a new beloved - 18-year-old Natalya Kazakevich, whom he noticed in the Hermitage library, at the table opposite. According to conflicting information, Gumilyov even wooed the girl, but the parents insisted on breaking off the relationship. Simultaneously with Kazakevich, Lev Nikolaevich was courting the proofreader Tatyana Kryukova, who read his articles and books.

The affair with Inna Nemilova, a married beauty from the Hermitage, lasted until the writer's marriage in 1968.

Lev Gumilyov met his wife Natalya Simonovskaya, a Moscow graphic artist, 8 years younger, in the capital in the summer of 1966. The relationship developed slowly, there was no seething of passions. But the couple lived together for 25 years, and the writer's friends called the family ideal: the woman devoted her life to her talented spouse, leaving all her previous occupations, friends and work.

The couple did not have children: they met when Lev Gumilyov was 55, and the woman was 46. Thanks to Natalia Gumileva and her efforts, the couple in the mid-1970s moved to a more spacious communal apartment on Bolshaya Moskovskaya. When the house sank because of the construction unfolding nearby, the couple moved to an apartment on Kolomenskaya, where they lived until the end of their lives. Today the museum of the writer is open here.

Death

In 1990, Lev Gumilyov was diagnosed with a stroke, but the scientist took up work as soon as he got out of bed. After 2 years, his gallbladder was removed. The operation was difficult for a 79-year-old man - bleeding began.

For the last 2 weeks, Gumilyov was in a coma. He was disconnected from life support devices on June 15, 1992.

They buried Akhmatova's son next to the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, at the Nikolskoye cemetery.

In September 2004, next to the grave of Lev Gumilyov, the grave of his wife appeared: Natalya survived her husband for 12 years.

- Gumilyov did not speak to his mother for the last 5 years of her life. In Requiem, Akhmatova called Lev “you are my son and my horror”.

- Gumilyov did not tolerate potatoes and believed that it seriously complicated the life of the Russian peasant. Natalya Viktorovna cooked soup with turnips instead.

- On principle, Gumilyov came to the station an hour before departure - what if they send it earlier?

- Lev Gumilyov visited abroad for the only time in 1966, having made a trip to an archaeological congress in Prague.

- At the end of his life, the writer fell in love with detective stories and science fiction. He preferred creativity, and,.

- Gumilyov tolerated drunkenness and smoking. He himself argued that "vodka is a psychological concept." Gumilyov smoked "Belomorkanal" for the rest of his life, setting fire to a new cigarette from a burned out one. He believed that smoking was not harmful.

- A peculiar feature of Gumilyov's personality was Turkophilia. Since the 1960s, he increasingly signed his letters "Arslan-bek" (translation of the name Lev into Turkic).

Bibliography

- 1960 - "Hunnu: Central Asia in Ancient Times"

- 1962 - "The Feat of Bahram Chubina"

- 1966 - "Discovery of Khazaria"

- 1967 - "Ancient Turks"

- 1970 - The Search for a Fictional Kingdom

- 1970 - "Ethnogenesis and Ethnosphere"

- 1973 - "Huns in China"

- 1975 - "Staroburyat painting"

- 1987 - "Millennium around the Caspian Sea"

- 1989 - "Ethnogenesis and the biosphere of the Earth"

- 1989 - "Ancient Russia and the Great Steppe"

- 1992 - "From Russia to Russia"

- 1992 - "The End and the Beginning Again"

- 1993 - "Ethnosphere: the history of people and the history of nature"

- 1993 - "From the history of Eurasia"