Population of ancient Rus' (IX - X centuries). Population of Rus', Russia, USSR and percentage of urban population Domestic and foreign policy of Kievan Rus during the reign of Oleg the Prophet

Over the years of searching for disappeared villages, I have often encountered a paucity of finds in villages of the 10th-16th centuries. Why are there practically no objects? Maybe these are not villages at all, but what kind of sheds stood there? The question interested me, and I studied it in detail. Looking at the increasing occurrence of topics on the forum about “wastelands”, “search in ravines”, “scribal villages”, and other search options that end in disappointment for the authors, I decided to briefly outline what I myself have encountered.

Population size.

Studies of the population of ancient Rus' and the medieval period were rarely carried out, and no one reflected the exact picture, which in general is impossible. We can only say approximately, with a certain percentage. Nevertheless, the essence of the issue is reflected correctly - and the error is not fundamental. During excavations, all this is confirmed in practice. According to the calculations of scientists (including Vernadsky and Tikhomirov), in the 10th-13th centuries about 4-5 million people lived on the territory of Rus' (the number of known architectural monuments + adjustment for those not discovered) - this is double less than the population of modern Moscow...

Even if the figure is underestimated, it can be doubled (purely theoretically smile.gif) - and even 10 million relative to the entire territory is an insignificant amount. During the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols, this number decreased and an outflow of population was observed. The same picture is typical for the 14th and 15th centuries, but some increase was still observed - it turned out to be approximately 5.5 million. Only at the end of the 15th century, due to the strengthening of the Moscow state, an influx of population began, slow but sure. From the notes of some foreign travelers who visited Muscovy, one could travel many miles along the roads without meeting a single person...

By the way, in the 17th century, about 7-10 million people lived in Russia, under Peter the Great - about 15 million people, but by the reign of Catherine the Second, this figure increased to 36 million! Let's move on - cities. In the 6th-10th centuries, the average number of inhabitants of the city (fortification) was about 100 people - and this is a city! By the 10th century, the urban population increased sharply - migration from the southern regions was observed. The population of an average city (there were about 200-300) is about 1000 people. In such large cities as Kiev, Smolensk, Novgorod, Suzdal, etc. (and there were about 20 of them) - from 10,000 to 40,000 people lived - but most scientists do not agree with this figure - they consider it to be greatly overestimated .

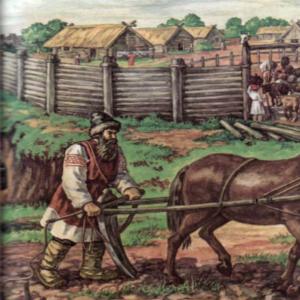

Endure villages and villages. Based on archaeological data, it is easy to determine the number and area of courtyards, and, accordingly, the number of inhabitants. Here's what happens according to statistics: the number of inhabitants of a rural settlement in the 10th-13th centuries was from 10 to 50 people - that's 1-5 households in each. 50 people is practically a village - a large village for those times, which should have been located in a good place - a large river, a busy road, etc. Villages with a number of souls of 15-20 are the average statistics of villages for pre-Mongol times. Less than 15 people, i.e. 1-2 households - peripheral villages located far from trade routes, large rivers and busy roads. They are characterized by an extremely low standard of living, despite the fact that they are the overwhelming majority - approximately 50% of the total number of settlements. During the period of the Tatar-Mongol invasion, these figures certainly fell, both in the number of people and in the number of settlements themselves.

This picture is observed throughout the 14th – early 15th centuries. This is due to the same enemy raids. During the reign of Ivan III, some improvements were observed, but they concerned mainly the cities - the entire population was concentrated in the centers of craft and trade, and the countryside remained in the same state. Only in the 16th century were favorable conditions created for the countryside - the state strengthened as a centralized state. In the 17th century, villages already had at least 5 households or more. Villages of one yard became a minority.

Material values. Metals. As you know, the main raw material for obtaining iron kritsa in Rus' was bog ore. It is formed due to the decomposition of swamp plants over many years - a piece of this ore contains only 1-2% metal... It was mined naturally by hand - floating through the swamps on rafts and scooping them up from the bottom. It is worth noting that not every swamp has it, and not every bucket has scooped it out. You can imagine how much ore is needed to make, say, an ordinary knife - I think it’s at least a ton... But that’s not all - in order to get metal from it, you need to go through a processing (reduction) process.

First, it was dried, cleaned of dirt and excess impurities, crushed, then burned in specially prepared pits, while being blown with bellows... this is a very complex and labor-intensive process, and not much metal was obtained at all. Therefore, iron was very valuable and expensive. Many people wonder why ancient knives were so small? That is why. They took care of iron, and even broken things were not thrown away, but were taken to the blacksmith for reforging into new ones. What can I say - after the fires, all the iron was taken out of the ashes... After the battle, everything was collected to the last nail... That is why in ancient settlements there was even very little iron. A small digression: - disputes about the location of the Battle of Kulikovo, for example, are simply ridiculous. The same applies to many battles of the Middle Ages - when a huge amount of iron was scattered on the field, not a single sane person of those times would have passed by...

They swept away any iron fragment - after all, it’s easier to loosen up the entire field than to extract crumbs from the swamp ore... Let’s continue. Non-ferrous metals. In Rus' there were no developed deposits of color-meth - i.e. There was no own production at all! Copper, tin, silver, gold - all this was imported and therefore cost quite a lot. In the 10th-13th centuries they were brought mainly from Byzantium and Europe - and here jewelers were already making products. There were practically no copper deposits of our own until the 17th century. The first silver was mined in Russia in 1704. With gold it’s even more difficult... It’s not difficult to guess that these metals were very cherished, and all the scrap was melted down to make new products. Not a single crumb was wasted. Nowadays you can throw a coil of copper wire in the trash, but back then everything was collected and put into use. I don’t think it’s worth explaining how valuable even ordinary copper was, if every piece of iron was saved to the last...

So when they left the settlement, all metal objects, if possible, were selected and taken with them. This was a common occurrence - there was no metal lying on the road. He was too expensive. And in general, little was made of metal - basically all household items were made of wood, bone or clay. Here it is - medieval reality... There were practically no people, and even less valuables. Imagine a village from the 15th century. Ordinary, average, unremarkable, located away from the roads, on dry land - 2 yards and 12 inhabitants.

They live their lives leisurely, and suddenly one fine day the Crimeans slaughter everyone, rob them, and burn their houses. Soon the enemies left, and the inhabitants of neighboring villages came to the ashes. They shook out all the ashes with sticks, selected iron objects, threw melts of color and metal into the bag, whoever got the ax was lucky! Nails were pulled out of charred logs, the charred bones of the dead were buried, they took their leave, and ran to the blacksmith to forge the pieces of iron into knives... This is how we lived.

A law cannot be a law if there is no strong force behind it.

Mahatma Gandhi

The entire population of Ancient Rus' can be divided into free and dependent. The first category included nobility and ordinary people who had no debts, were engaged in crafts and were not burdened with restrictions. With dependent (involuntary) categories, everything is more complicated. In general, these were people who were deprived of certain rights, but the entire composition of involuntary people in Rus' was different.

The entire dependent population of Rus' can be divided into 2 classes: those completely deprived of rights and those who retained partial rights.

- Serfs- slaves who fell into this position due to debts or by decision of the community.

- Servants- slaves who were purchased at auction were taken prisoner. These were slaves in the classical sense of the word.

- Smerda- people born into dependence.

- Ryadovichi- people who were hired to work under a contract (series).

- Purchases- worked off a certain amount (loan or purchase) that they owed, but could not repay.

- Tiuny- managers of princely estates.

Russian truth also divided the population into categories. In it you can find the following categories of the dependent population of Rus' in the 11th century.

It is important to note that the categories of the personally dependent population in the era of Ancient Rus' were smerds, serfs and servants. They also had complete dependence on the prince (master).

Completely dependent (whitewashed) segments of the population

The bulk of the population in Ancient Rus' belonged to the category of completely dependent. These were slaves and servants. In fact, these were people who, by their social status, were slaves. But here it is important to note that the concept of “slave” in Rus' and Western Europe was very different. If in Europe slaves had no rights, and everyone recognized this, then in Rus' slaves and servants had no rights, but the church condemned any elements of violence against them. Therefore, the position of the church was important for this category of the population and provided relatively comfortable living conditions for them.

Despite the position of the church, completely dependent categories of the population were deprived of all rights. This demonstrates well Russian Truth. This document, in one of its articles, provided for payment in the event of killing a person. So, for a free citizen the payment was 40 hryvnias, and for a dependent one - 5.

Serfs

Serfs - that’s what they called people in Rus' who served others. This was the largest stratum of the population. People who became completely dependent were also called " whitewashed slaves».

People became slaves as a result of ruin, misdeeds, and the decision of fiefdom. They could also become free people who, for certain reasons, have lost part of their freedom. Some voluntarily became slaves. This is due to the fact that a part (small, of course) of this category of the population was actually “privileged”. Among the slaves were people from the prince’s personal service, housekeepers, firemen and others. They were rated in society even higher than free people.

Servants

Servants are people who have lost their freedom not as a result of debt. These were prisoners of war, thieves, condemned by the community, and so on. As a rule, these people did the dirtiest and hardest work. It was an insignificant layer.

Differences between servants and slaves

How were servants different from serfs? It is as difficult to answer this question as it is today to tell how a social accountant differs from a cashier... But if you try to characterize the differences, then the servants consisted of people who became dependent as a result of their misdeeds. One could become a slave voluntarily. To put it even simpler: the slaves served, the servants did the work. What they had in common was that they were completely deprived of their rights.

Partially dependent population

Partially dependent categories of the population included those people and groups of people who lost only part of their freedom. They were not slaves or servants. Yes, they depended on the “owner”, but they could run a personal household, engage in trade and other matters.

Purchases

Purchases are ruined people. They were given to work for a certain kupa (loan). In most cases, these were people who borrowed money and could not repay the debt. Then the person became a “purchaser”. He became economically dependent on his master, but after he completely repaid the debt, he became free again. This category of people could be deprived of all rights only if the law was violated and after a decision by the community. The most common reason why Purchases became slaves was the theft of the owner's property.

Ryadovichi

Ryadovichi - were hired to work under a contract (row). These people were deprived of personal freedom, but at the same time retained the right to conduct personal farming. As a rule, the agreement was concluded with the land user and it was concluded by people who were bankrupt or unable to lead a free lifestyle. For example, series were often concluded for 5 years. Ryadovich was obliged to work on the princely land and for this he received food and a place to sleep.

Tiuny

Tiuns are managers, that is, people who locally managed the economy and were responsible to the prince for the results. All estates and villages had a management system:

- Fire Tiun. This is always 1 person - a senior manager. His position in society was very high. If we measure this position by modern standards, then the fire tiun is the head of a city or village.

- Regular tiun. He was subordinate to the fireman, being responsible for a certain element of the economy, for example: crop yield, raising animals, collecting honey, hunting, and so on. Each direction had its own manager.

Often ordinary people could get into tiuns, but mostly they were completely dependent serfs. In general, this category of the dependent population of Ancient Rus' was privileged. They lived in the princely court, had direct contact with the prince, were exempt from taxes, and some were allowed to start a personal household.

All early medieval authors who wrote about the Slavs noted their extreme numbers. But these reviews must be taken in the context of the sharp decline in the Western European population in the early Middle Ages due to wars, epidemics and famine.

Demographic statistics of the 9th - 10th centuries. for ancient Rus' it is extremely conventional. Figures were cited from 4 to 10 million people for Eastern Europe as a whole (including for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland - 2.5 million) [History of the peasantry in Europe. In 2 vols. M., 1985. T. 1. P. 28]. It should be taken into account that the Old Russian population included more than two dozen non-Slavic peoples, but in percentage terms the Eastern Slavs undoubtedly prevailed. Population density was generally low and varied in different parts of the country; the greatest concentration was on the Dnieper lands.

Demographic growth was hampered by a number of natural and social factors. According to researchers, wars, famine and disease took away about a third of the population. The Tale of Bygone Years preserved news of no less than three severe famines in the 11th century. In fact, there were more of them (see http://simbir-archeo.narod.ru/klimat/barash2.htm), and before they probably happened even more often. Indeed, even in the Rhine Valley - one of the most developed areas of Europe with a long-established system of production of material goods - at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia, severe hunger strikes were renewed at intervals of three to four years. According to Arab writers, famine in the Slavic lands did not arise from drought, but, on the contrary, due to the abundance of rain, which is fully consistent with the climatic characteristics of this period, marked by general warming and humidification.

As for diseases, the main cause of mass death of people, especially children, was rickets and various types of infections. The Arab historian al-Bekri left news that the Slavs especially suffer from erysipelas and hemorrhoids (“there is hardly anyone among them who is free from them”), but its reliability is doubtful, since there is no strict connection between these diseases and the sanitary and hygienic living conditions of that time does not exist. Among the seasonal diseases among the Eastern Slavs, al-Bekri especially highlighted the winter runny nose. This very common malaise for our latitudes so struck the Arab writer that it wrested a poetic metaphor from him. “And when people let water out of their nose,” he writes, “their beards become covered with layers of ice, like glass, so you have to break them until you warm up or come to your home.”

Due to high mortality, the average lifespan of an Eastern European was 34 - 39 years, while the average female age was a quarter shorter than that of a male, as girls quickly lost their health due to early marriage (between 12 and 15 years). The result of this state of affairs was small children. In the 9th century. Each family had an average of one or two children.

In the absence of populous cities, which in later times weakened the marital isolation of peasant society, the circle of people in Slavic settlements who entered into a marriage union was very limited, which had a bad effect on heredity. To avoid genetic degeneration, some tribes resorted to bride kidnapping. According to the chronicle, this method of marriage was customary among the Drevlyans, Radimichi, Vyatichi and Northerners.

In general, rather slow demographic growth became noticeable only in the 10th century, when population density increased noticeably, especially in river valleys. Caused by the development of productive forces, this process, in turn, stimulated their further progress. The increased need for grains influenced the transition in agriculture from rawl to plow in the forest-steppe zone and from rawl to plow in the forest, with the simultaneous introduction of two-field farming. And the influx of workers contributed to wider clearings of forests and plowing of new lands.

As the population grew, the ancient Russian landscape gradually changed. The forests of the Ilmen region thinned out to a large extent precisely after Slavic settlers were added to the mass of the native Finnish population. And in the Northern Black Sea region, where the pine forests were settled by the Scythians and Sarmatians, with the settlement of the East Slavic tribes here, the forest border retreated even further to the north.

The population of Kievan Rus was one of the largest in Europe. Its main cities - Kyiv and Novgorod - were home to several tens of thousands of people. These are not small towns by modern standards, but, given the one-story buildings, the area of these cities was not small. The urban population played a vital role in the political life of the country - all free men participated in the assembly.

Political life in the state affected the rural population much less, but the peasants, who remained free, had elected self-government longer than the townspeople.

Historians distinguish the population groups of Kievan Rus according to the “Russian Truth”.

According to this law, the main population of Rus' were free peasants, called "people".

Over time, more and more people became stinkers- another group of the population of Rus', which included peasants dependent on the prince. Smerd, like an ordinary person, as a result of captivity, debts, etc. could become a servant (later name - serf).

Serfs They were essentially slaves and were completely powerless.

In the 12th century there appeared procurement- incomplete slaves who could redeem themselves from slavery. It is believed that there were still not so many slave slaves in Rus', but it is likely that the slave trade flourished in relations with Byzantium. "Russkaya Pravda" also highlights rank and file And outcasts. The former were somewhere at the level of serfs, and the latter were in a state of uncertainty (slaves who received freedom, people expelled from the community, etc.).

A significant group of the population of Rus' were artisans. By the 12th century there were more than 60 specialties. Rus' exported not only raw materials, but also fabrics, weapons and other handicrafts.

Merchants were also city dwellers. In those days, long-distance and international trade meant good military training. Initially, warriors were also good warriors. However, with the development of the state apparatus, they gradually changed their qualifications, becoming officials. However, combat training was needed by the vigilantes, despite the bureaucratic work. They stood out from the squad boyars- the closest to the prince and rich warriors. By the end of the existence of Kievan Rus, the boyars became largely independent vassals; the structure of their possessions as a whole repeated the state structure (their own land, their own squad, their own slaves, etc.).

Categories of the population and their position

Prince of Kyiv- the ruling elite of society.

Druzhina- the administrative apparatus and the main military force of the Old Russian state. Their most important duty was to ensure the collection of tribute from the population.

Older(boyars) - The prince’s closest associates and advisers, with them the prince first of all “thought” about all matters, resolved the most important issues. The prince also appointed boyars as posadniks (representing the power of the Kyiv prince, belonging to the “senior” warriors of the prince, who concentrated in his hands both military-administrative and judicial power, and administered justice). They were in charge of individual branches of the princely economy.

Junior(youths) - Ordinary warriors who were the military support of the mayor’s power.

Clergy— The clergy lived in monasteries, the monks refused worldly pleasures, lived very poorly, in labor and prayer.

Dependent Peasants- Slave position. Servants - slaves-prisoners of war, serfs were recruited from the local environment.

Serfs(servants) - These were people who became dependent on the landowner for debts and worked until the debt was repaid. Purchases occupied an intermediate position between slaves and free people. The purchase had the right to buy out by repaying the loan.

Purchases— Out of necessity, they entered into contracts with the feudal lords and performed various works according to this series. They often acted as minor administrative agents for their masters.

Ryadovichi— Conquered tribes who paid tribute.

Smerda- Prisoners imprisoned on the ground who bore duties in favor of the prince.

Demography

All early medieval authors who wrote about the Slavs noted their extreme numbers. But these reviews must be taken in the context of the sharp decline in the Western European population in the early Middle Ages due to wars, epidemics and famine.

Demographic statistics of the 9th - 10th centuries. for ancient Rus' it is extremely conventional. Figures were cited from 4 to 10 million people for Eastern Europe as a whole (including for the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland - 2.5 million) [History of the peasantry in Europe. In 2 vols. M., 1985. T. 1. P. 28]. It should be taken into account that the Old Russian population included more than two dozen non-Slavic peoples, but in percentage terms the Eastern Slavs undoubtedly prevailed. Population density was generally low and varied in different parts of the country; the greatest concentration was on the Dnieper lands.

Demographic growth was hampered by a number of natural and social factors. According to researchers, wars, famine and disease took away about a third of the population. The Tale of Bygone Years preserved news of two severe famines in the 11th century, which became the causes of major popular unrest in North-Eastern Russia (True, hunger strikes caused by climatic conditions became common only in the period from the end of the 13th to the beginning of the 17th century, when there was a certain deterioration in the climate towards cooling and aridity.) According to Arab writers, famine in the Slavic lands in the 9th-12th centuries. did not arise from drought, but, on the contrary, due to the abundance of rain, which is fully consistent with the climatic characteristics of this period, marked by general warming and humidification.

As for diseases, the main cause of mass death of people, especially children, was rickets and various types of infections. The Arab historian al-Bekri left news that the Slavs especially suffer from erysipelas and hemorrhoids (“there is hardly anyone among them who is free from them”), but its reliability is doubtful, since there is no strict connection between these diseases and the sanitary and hygienic living conditions of that time does not exist. Among the seasonal diseases among the Eastern Slavs, al-Bekri especially highlighted the winter runny nose. This very common malaise for our latitudes so struck the Arab writer that it wrested a poetic metaphor from him. “And when people let water out of their nose,” he writes, “their beards become covered with layers of ice, like glass, so you have to break them until you warm up or come to your home.”

Due to high mortality, the average lifespan of an Eastern European was 34 - 39 years, while the average female age was a quarter shorter than that of a male, as girls quickly lost their health due to early marriage (between 12 and 15 years). The result of this state of affairs was small children. In the 9th century. Each family had an average of one or two children.

In the absence of populous cities, which in later times weakened the marital isolation of peasant society, the circle of people in Slavic settlements who entered into a marriage union was very limited, which had a bad effect on heredity. To avoid genetic degeneration, some tribes resorted to bride kidnapping. According to the chronicle, this method of marriage was customary among the Drevlyans, Radimichi, Vyatichi and Northerners.

In general, rather slow demographic growth became noticeable only in the 10th century, when population density increased noticeably, especially in river valleys. Caused by the development of productive forces, this process, in turn, stimulated their further progress. The increased need for grains influenced the transition in agriculture from rawl to plow in the forest-steppe zone and from rawl to plow in the forest, with the simultaneous introduction of two-field farming. And the influx of workers contributed to wider clearings of forests and plowing of new lands.

As the population grew, the ancient Russian landscape gradually changed. The forests of the Ilmen region thinned out to a large extent precisely after Slavic settlers were added to the mass of the native Finnish population. And in the Northern Black Sea region, where the pine forests were settled by the Scythians and Sarmatians, with the settlement of the East Slavic tribes here, the forest border retreated even further to the north.

Ethnic composition

The Russian land was divided ethnically into the Rus - the inhabitants of the Russian/Kievan land itself, the Slovenes - the East Slavic tribes subordinate to the Rus, and the languages (languages) - national minorities: the Finno-Ugric and Baltic peoples. Each of these groups, in turn, represented a motley world of tribal characteristics and assimilation processes. Archaeological studies of the Middle Dnieper region showed that “in the land of the glades (Kyiv land - S. Ts.) in general there was no predominance of any one archaeological culture. The Glades themselves are perhaps the most archaeologically mysterious tribe. The territory of their supposed residence is a picture of a mixture of ethnic groups and cultures, a kind of “marginal zone” [ Korolev A.S.. The history of inter-princely relations in Rus' in the 40s - 70s of the 10th century. M., 2000. P. 36]. The East Slavic element here coexists with West Slavic (“Varangian” and Moravian), Alan and Turkic monuments.

Igor's state embraced, in addition to the Middle Dnieper, the tribal territories of the Drevlyans, Krivichi (Smolensk), Dregovich, Northerners, Uglich, Tivertsi, Duleb (Volynians), White Croats, Radimichi. All these tribes mixed with each other and with their foreign-language neighbors in all sorts of combinations. The Uglich and Tivertsi people were gradually dissolved into the Turkic-speaking steppe. The Drevlyans disappeared into the mass of inhabitants - Volynians, Dregovichi and Alan-Turkic inhabitants of the Kyiv land. The Smolensk Krivichi, Dregovichi and Radimichi absorbed the Balto-Finnish tribes of the Upper Dnieper, Ponemania and Volga-Klyazma interfluves. The northerners merged with the Iranian-speaking inhabitants of the Dnieper left bank*. The Dulebs and White Croats maintained ties with the Western Slavs - Poles, Moravians, Czechs. In general, tribal differences were erased in the south much faster than in the north.

*Skulls of the Slavs on the left bank of the Dnieper are similar to skulls from the burials of the Saltivka culture (Alekseev V.P. Anthropology of the Saltivsky burial ground. // Materials from anthropologists of Ukraine. Kiev, 1962. P. 88). A number of local water names indicate that the native, pre-Slavic population of these places were the Balts and Sarmatians ( Toporov V.N., Trubachev O.N.. Linguistic analysis of hydronyms in the Upper Dnieper region. M., 1962. S. 229, 230).

Social division

The social stratification of ancient Russian society of the 10th century, on the contrary, was distinguished by great simplicity. The division of the population by place of residence into townspeople and villagers was barely defined and was very conditional, since cities were still a special type of tribal settlements, “fenced places,” and the bulk of their inhabitants continued to engage in agriculture. The boundaries between primary professional groups were equally unsteady and blurred. A warrior, a merchant, a craftsman, and a farmer could exist in one person, only with some predominance of one of these occupations. Social levels were almost indistinguishable: rich, poor, etc.

The class structure of society became much clearer. The distinction here was made along the most noticeable, but also the most general line, which was determined by the presence or absence of a person’s personal freedom. According to this section, the ancient Russian population was divided into free people and slaves.

Free people were called men, without distinction between rich and poor, noble and ignorant. The nobility, however, were called the best men, but only in the sense of aristocracy, the nobility of the breed; “better” did not mean “freer” or “privileged.” Old Russian freedom was a product of clan society and was conceived in terms characteristic of this society. The bearer of freedom was a social group, most often a community, which was like a collective womb producing free people; the personality was free insofar as from birth it recognized itself as part of a free collective. Staying in the community fostered not an internal sense of personal freedom, but a corporate consciousness of belonging to the class of the free. Equality of status was felt only in communication with one’s own kind. Old Russian man trusted his freedom with the freedom of others and was completely alien to any attempts to self-determinate his position in the group as a self-sufficient individual. As a result of this, he felt not essentially free, always equal to himself and other people, regardless of external circumstances, but free - not knowing any other master over himself who would constrain him in his actions other than custom. The criterion of freedom, therefore, has always been external to the individual: I am free because, firstly, I am recognized as such by free members of the community and, secondly, my will cannot be grossly infringed upon by another person.

Losing contact with the community turned the husband into an outcast. The very etymology of this word - “outlived”, “social exile”, “deprived of care” (from the Slavic goiti - “to live”, as well as “to let live”, “to take care”) - shows that the freedom of the outcast was under serious threat. Realizing this, society took the outcasts under its protection. They were given the right to live on the territory of another community, taking advantage of their position as a free person.

Slaves made up a large part of the population of the Russian land. The overwhelming majority were captured foreigners. To designate a captive slave in Rus', the special term servants was used, in the plural - servants. The enslavement of their fellow tribesmen, free husbands, took place in exceptional cases when Russian law provided for the forcible deprivation of the rights of a free state as a criminal punishment for especially serious crimes.

Between the free and the slaves there was a thin intermediate layer formed by freedmen and other former slaves who had regained their freedom in one way or another. Being formally free, they, however, like outcasts, needed the patronage of society or influential people and therefore for the most part remained in the service of their former masters, being classified as senior servants.