Ivan Aivazovsky distribution of food 1892. Aivazovsky's will

One of two paintings by Ivan Aivazovsky dedicated to American aid to starving Russian peasants. The Stars and Stripes and the worship of the hungry peasants are clearly visible on the canvas.

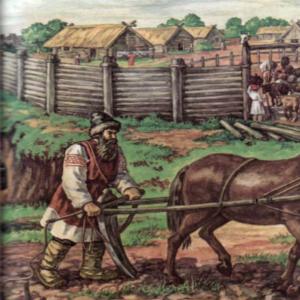

Aivazovsky’s painting “Distribution of Food,” painted by the artist in 1892, is one of those that was not welcomed to be shown in modern Russia. On the Russian troika, loaded with American food, stands a peasant, proudly raising the American flag above his head. Villagers wave scarves and hats, and some, falling into the roadside dust, pray to God and praise America for its help. The film is dedicated to the American humanitarian campaign of 1891–1892 to help starving Russia.

The future Emperor of Russia Nicholas II said: “We are all deeply touched that ships full of food are coming to us from America.” The resolution, prepared by prominent representatives of the Russian public, read, in part: “By sending bread to the Russian people in times of hardship and need, the United States of America is showing a most moving example of fraternal feelings.”

Prince Alexander Mikhailovich, cousin of Nicholas II:

“The difficulties facing the American government were no less than ours, but our asset was greater. Russia had gold, copper, coal, iron; Its soil, if it were possible to increase the productivity of the Russian land, could feed the whole world. What was Russia missing? Why couldn't we follow the American example? Here, four thousand miles from the European cockfights, a living example of the country's capabilities under conditions similar to those of Russia was presented to the observer. We should have just put a little more common sense into our policies..."

On the same topic - “Help Ship”, Aivazovsky

The second painting by Ivan Aivazovsky, dedicated to the arrival of American aid to the ports of the Russian Empire.

At the end of the 19th century, Americans saved Russians from starvation. The memory of this incident is documented in an unusual way - in the paintings of Ivan Aivazovsky

Russians have a short memory: according to opinion polls, they consider the United States enemy No. 1, having forgotten that the United States has repeatedly helped their country. This was the case during both world wars - official Washington was not only an ally, but also helped with loans and various equipment. And shortly before the First World War, ordinary Americans literally saved the mighty, as it seemed to many then, Russian Empire from famine.

Even artistic evidence of this has been preserved - paintings painted by the famous Russian marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky.

In April 1892, he watched as American ships loaded with wheat and corn flour arrived at the Baltic ports of Liepaja and Riga. In Russia they were eagerly awaited, since for almost a year the empire had been suffering from famine caused by crop failure.

A crumbling hut of a starving Tatar peasant in one of the villages of the Nizhny Novgorod province (photo from 1891-1892) Photo: Maxim Dmitriev, DR

The authorities did not immediately agree to the offer of help from US philanthropists. There were rumors that the then Russian Emperor Alexander III commented on the food situation in the country as follows: “I have no starving people, only those affected by crop failure.”

However, the American public persuaded St. Petersburg to accept humanitarian aid. Farmers from the states of Philadelphia, Minnesota, Iowa and Nebraska collected about 5 thousand tons of flour and sent it with their own money - the amount of assistance amounted to about $1 million - to distant Russia. Some of these funds also went towards regular financial assistance. In addition, American public and private companies offered long-term loans worth $75 million to Russian farmers.

Aivazovsky wrote two paintings on this topic - Food Distribution and Aid Ship. And he donated both to the Washington Corcoran Gallery. It is unknown whether he witnessed the scene of the arrival of bread from the United States to the Russian village depicted in the first painting. However, the atmosphere of universal gratitude to the American people in that hungry year was much greater than in modern Russia.

If the paintings had remained in the Russian Federation, perhaps the Russians would have retained a sense of gratitude to the Americans.

“Unexpected” disaster

“The autumn of 1890 was dry,” wrote Dmitry Natsky, a lawyer from the Russian city of Yelets, located near Lipetsk, in his memoirs. “Everyone was waiting for rain, they were afraid to sow winter crops in dry soil and, without waiting, they began to sow in the second half of September.” .

Censorship began to erase from newspaper columns the words hunger, hungry, - Prince Vladimir Obolensky, publisher, about the famine of 1891-1892

He goes on to point out that what was sown almost never came up anywhere. After all, the winter had little snow, with the first warmth of spring the snow quickly melted away, and the dry soil was not saturated with moisture. “Until May 25, there was a terrible drought. On the night of the 25th, I heard the babbling of streams outside and was very happy. The next morning it turned out that it was not rain, but snow, it became very cold, and the snow melted only the next day, but it was too late. And the threat of crop failure became real,” Natsky continued to recall. He also pointed out that they ended up harvesting a very poor rye harvest.

Drought was widespread in the European part of Russia. The writer Vladimir Korolenko described this disaster that befell the Nizhny Novgorod province in the following way: “The clergy with prayers passed through the drying fields every now and then, icons were raised, and clouds stretched across the hot sky, waterless and stingy. From the Nizhny Novgorod mountains the lights and smoke of fires were constantly visible in the Volga region. The forests were burning all summer, catching fire on their own.”

Western illustration - hungry peasants crowd in search of food in St. Petersburg, DR

The previous few years were also poor harvests. In Russia, for such cases, since the time of Catherine II, there has been a system of assistance to peasants. She was involved in the organization of so-called local food stores. These were ordinary warehouses in which grain was stored for future use. In lean years, the regional administration lent grain from them to the peasants.

At the same time, by the end of the 19th century, the Russian government got used to constant cash receipts from grain exports. In good years, more than half of the harvest was sold to Europe, and the treasury received more than 300 million rubles annually.

In the spring of 1891, Alexey Ermolov, director of the non-salary collections department, wrote a note to Finance Minister Ivan Vyshnegradsky, warning about the threat of famine. The government conducted an audit of food stores. The results were frightening: in 50 provinces they were filled by 30% of the norm, and in 16 regions where the harvest was the lowest - by 14%.

However, Vyshnegradsky said: “We won’t eat it ourselves, but will export it.” The export of grain continued throughout the summer months. That year, Russia sold almost 3.5 million tons of bread.

When it became clear that the situation was truly critical, the government ordered a ban on grain exports. But the ban lasted only ten months: large landowners and businessmen, who had already bought up grain for export abroad, became indignant, and the authorities followed their lead.

The following year, when famine was already raging in the empire, the Russians sold even more grain to Europe - 6.6 million tons.

People's canteen in one of the villages affected by famine / Photo: Maxim Dmitriev, DR

Meanwhile, the Americans, having heard about the enormous famine in Russia, collected bread for the starving. Not knowing that grain traders' warehouses are filled with export wheat.

It was not only traders who ignored the famine; at first the authorities did not recognize that there was a real disaster in the country. Prince Vladimir Obolensky, a Russian philanthropist and publisher, wrote about this: “Censorship began to erase the words hunger, hungry, starving from newspaper columns. Correspondence that was prohibited in newspapers was passed around in the form of illegal leaflets, private letters from the starving provinces were carefully copied and distributed.”

Chronic malnutrition was supplemented by diseases, which, given the then existing level of medicine in the empire, turned into a real pestilence. Sociologist Vladimir Pokrovsky estimated that by the summer of 1892 at least 400 thousand people had died due to famine. This is despite the fact that in villages, records of the dead were not always kept.

Remember the good

On November 20, 1891, William Edgar, an American publisher and philanthropist from Minneapolis, who owned the then quite influential Northwestern Miller magazine, sent a telegram to the Russian embassy. From his European correspondents he learned that there was a real humanitarian catastrophe in Russia. Edgar proposed organizing a collection of funds and grain for a country in distress. And he asked Ambassador Kirill Struve to find out from the Tsar: would he accept such help?

A week later, without receiving any response, the publisher sent a letter with the same content. The embassy responded a week later: “The Russian government accepts your proposal with gratitude.”

Sociologist Vladimir Pokrovsky estimated that at least 400 thousand people died due to famine by the summer of 1892

That same day, Northwestern Miller issued a fiery appeal. “There is so much grain and flour in our country that this food is about to paralyze the transport system. We have so much wheat that we won't be able to eat it all. At the same time, the most mangy dogs roaming the streets of American cities eat better than Russian peasants.”

Edgar sent letters to 5 thousand grain traders in the eastern states. He reminded his fellow citizens that at one time Russia helped the United States a lot. In 1862–63, during the Civil War, the distant empire sent two military squadrons to the American coast. Then there was a real threat that British and French troops would come to the aid of the slave-owning south, with which the industrial one was at war. Russian ships then stood in American waters for seven months - and Paris and London did not dare to get involved in a conflict with Russia as well. This helped the northern states win that war.

Another Western illustration depicting what would be repeated in Ukraine in the 1930s - Cossacks riding through a Russian village in search of grain, Maxim Dmitriev, DR

Almost everyone to whom he sent letters responded to William Edgar's call. The fundraising movement for Russia has spread throughout the United States. The New York Symphony Orchestra gave benefit concerts. Opera performers picked up the baton. As a result, the artists alone raised $77 thousand for the distant empire.

The Americans spent three months delivering humanitarian flour. Already on March 12, 1892, the steamships Missouri and Nebraska set off for Russia with a cargo of aid. Edgar himself swam to Berlin, and traveled to St. Petersburg by train. At the border he suffered his first shock. “The Russian customs officers were so strict that I felt like a rat in a trap,” wrote the traveler. Edgar was struck by the Russian capital - its luxury did not really correspond to the starving country. Moreover, they greeted him according to local tradition with bread and salt in a silver salt shaker.

Then the American philanthropist traveled through famine-stricken regions. It was there that he saw the real Russia. “In one village I watched a woman prepare dinner for her family. Some kind of green herb was boiled in a pot, to which the hostess threw in a couple of handfuls of flour and added half a glass of milk,” Edgar later wrote in his journal.

He was also struck by the scenes of the distribution of humanitarian aid he had brought. One distribution official allowed hungry peasants to take as much as they could carry. “Exhausted people shouldered a sack of flour and, barely moving their legs, dragged it to their families,” Edgar reported.

There were also some oddities familiar to Russia, which were incomprehensible to an American. Already in Liepaja, part of the humanitarian aid disappeared without a trace. Edgar was warned that local merchants would resort to any tricks for profit. A month earlier, the government purchased 300 thousand pounds of grain. It turned out that almost all of it was mixed with soil and was therefore unsuitable for consumption.

Ashes of history

The Americans greatly eased the lives of starving regions and in return received sincere gratitude from the main recipients of assistance - ordinary peasants. This impressed Aivazovsky, who wrote two paintings about American aid at once.

But the famine, as well as the marine painter’s paintings taken to Washington, were soon forgotten in Russia. As, indeed, about the movement started by William Edgar.

Only in 1962 did American newspapers begin to write about all this. Then the USA and the USSR found themselves on the brink of nuclear war due to the deployment of Soviet missiles in Cuba. And the Americans tried to find common ground in the past.

US First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy borrowed Aivazovsky's paintings from the Corcoran Gallery for a conference room in the White House. Against their background, the president and his press secretaries made statements on the progress of clarifying relations with Moscow. Aivazovsky’s paintings, according to the American side, were reminiscent of past fraternal feelings between the two peoples.

The historical paintings were sold at Sotheby’s auction for $2.4 million in 2008. The buyers, private individuals, are unknown.

Follow us

It's been a while since I wrote stories about Russian-American relations here. Not because they are over - not at all, it’s just that time is becoming less and less, and deadlines are becoming more and more. But still...

Let's talk about Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky. Yes, he also visited the United States, and, as best he could, contributed to the formation of the image of Russia in this country. The marine painter ended up in the USA in 1892-1893.

I.K.

I.K. Aivazovsky. Self-portrait

. 1892

Arriving overseas in the year celebrating the discovery of America, Aivazovsky could not ignore the “Columbus theme.” In New York he writes "The Departure of Columbus from Palos."

I.K Aivazovsky. Columbus's departure from Palos.

1893

Aivazovsky traveled around the USA, and even tried his hand at depicting an unusual state of water for him - not the sea element, but a falling stream:

I.K. Aivazovsky. Niagara Falls . 1894(?)

Aivazovsky's works were presented in the Russian section of the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago (along with paintings by F. Vasiliev, K. Korovin, K. Makovsky, V. Perov, I. Repin, G. Semiradsky, P. Trubetskoy, I. Shishkin and others, - 133 paintings in total):

The artist arrived in the United States at the height of the country's relief campaign for those suffering from the famine of 1891-1892. Russia; even before leaving, he witnessed the enthusiastic welcome given in Russia to ships with food sent by American philanthropists (the so-called “famine fleet” - Famine Fleet). In 1892, Aivazovsky captured this event in two paintings - “Relief Ship” (according to other sources, the original title of this painting was “The Arrival of the Missouri Steamship with Bread to Russia”) and “Distribution of Food”.

I.K. Aivazovsky. Relief ship

. 1892

I.K. Aivazovsky. Food distribution.

1892

The second picture is especially interesting. On the Russian troika, apparently loaded with American food, is a peasant, proudly raising an American flag above his head. Villagers wave scarves and hats, and some, falling into the roadside dust, pray to God and praise America for its help.

During his visit to the United States, the Russian artist donated paintings to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington. Subsequently, before they ended up in a private collection in Pennsylvania in 1979, the paintings were exhibited several times in the United States. From 1961 to 1964 they were exhibited at the White House. The initiator of the exhibition was J.F. Kennedy's wife, Jacqueline. She ordered the paintings to be hung in the room where the American president usually held conferences. The First Lady of the United States intended thereby to emphasize the deep sympathies of the Americans for the Russian people, to whom they always came to the aid and whom, by the way, they perceived separately from the government. Thus, in the second half of the twentieth century, Aivazovsky’s paintings contributed to maintaining the “romantic” image of folk Russia.

In turn, the artist himself in 1893, in an interview with The New York Evening Post, tried to soften the negative image of official Russia as a country of violence and tyranny, emphasizing that the Americans were distorting the meaning of discriminatory policies towards Russian Jews. They, Aivazovsky enlightened US citizens, are not a discriminated against ethnic group, but as heavy a burden for Russia as Chinese immigrants are for America.

The magazine "Free Russia" made critical comments about this interview. The editorial stated: " Of course, art is not the best field for the struggle against tyranny, and we cannot expect from the vast majority of artists even such a mild protest against imperialism as is present in Vereshchagin’s paintings. But what seems even more regrettable to us is the fact that artists like Aivazovsky, instead of painting, consider it necessary to speak out in defense of the Tsar and “historical friendship”... Professor Aivazovsky is deeply mistaken if he intends to find among sensible Americans those who advocate the introduction of the law against Chinese immigration, guided by the idea of its similarity to those in force in the Russian Empire".

Many predict that Russia will experience a whole series of constant economic problems and crises, which it has already entered into since 2014. What is economic devastation usually associated with? Of course, with empty refrigerators, in which only a stale can of canned fish and old pickled honey mushrooms from grandma remained.

But residents of the Russian Federation should not worry so much about their children, who in the future may swell from hunger. After all, the best friends in the world - American Pindos - will come to the rescue, as has happened more than once in history.

Famine in 1891-1892

In 1891, severe crop failure occurred in the Black Earth and Middle Volga regions. Areas with a population of 36 million people found themselves in an extremely unenviable position. And local authorities, who were required to have reserves for such cases, suddenly announced that there was no bread for a rainy day in the hangars. Well, here we go - crisis, famine, devastation, death, typhoid and cholera epidemics. Approximately 500 thousand people went to the next world, thanks to the wise actions of the tsarist regime. There could have been significantly more victims if not for the ubiquitous American Pindos.

Aivazovsky’s painting “The Arrival of the Missouri Steamship with Bread to Russia”, 1892.

Painting by Aivazovsky “Distribution of Food”. 1892

To provide humanitarian assistance in the United States, a special famine relief committee was formed - Russian Famine Relief Committee of the United States. Everything was sponsored by caring American citizens, who, through the Famine Fleet, began delivering tons of food to Russia by ship. The US government also provided some Russian provinces with a loan for the purchase of food in the amount of $75 million.

ARA (American Relief Administration) mission in the 1920s.

If in tsarist Russia famine was often associated with crop failures, which occurred periodically every 5-7 years, then in the 20s of the last century the situation looked much more apocalyptic. First World War, revolutions, Civil War. The population suffered from endless extortions for the needs of armies, all kinds of gangs and groups. The Bolsheviks confiscated every last grain as part of the food appropriation system, and killed those who disagreed.

A serious famine gripped the Volga region, where the population was eventually forced to eat grass, cats, dogs, and in critical cases, themselves. But the damned American Pindos, who always meddle in other people’s affairs all over the world, did not stand aside here either. As soon as news of the terrible famine reached the United States, a mission was urgently formed ARA(American Relief Administration) - American Relief Administration. Their help differed from other organizations (Red Cross, Nansen Committee, etc.) in that food went directly to those in need through their independent structures, and not through Bolshevik grabbers. Remembering the bitter experience of 1892, when Russian slow and thieving officials detained American grain in warehouses until it rotted, the ARA mission did everything itself.

In addition to food, the Americans widely supplied medicines, established hospitals, pharmacies, and medical aid stations. One of the pressing problems was the issue of vaccination - Russian peasants called vaccinations “the devil's spawn.” Then the ARA began to issue rations only with the appropriate medical certificate. As a result, 9 million people were vaccinated, which helped reduce the number of deaths from epidemics and diseases.

Residents of the Samara region knelt before the American who brought humanitarian aid

The APA mission was led by Herbert Hoover, the 31st President of the United States, who at that time served as Secretary of the Economy. At first, the Bolsheviks were reluctant to accept Western aid, fearing that taming the famine would arouse in Russian peasants “a spirit of freedom and attachment to bourgeois values.” And at first, the peasants themselves were distrustful of the ARA’s mission, because of the ARA’s focus on children, and not on adults, which, in the opinion of the village workers, was an unfair waste (after all, children can still be born). But after the Americans launched a broad food program for adults, opinion changed dramatically in a positive direction. The peasants even wrote letters demanding that they send portraits of Hoover to put them instead of icons in the red corner.

Hey, quilted man, he fed your grandfathers, and you don’t even know his name. HERBERT HOOVER, bitch!

ARA's mission became one of the largest food humanitarian campaigns of the 20th century. But Russian historians prefer to remain silent about this.

Committee "Help Russia in the War" during the Second World War.

« Thanks to the Russian people, the heroic people. He bore the brunt of the war, did not cave in, did not chicken out, and persevered. I urge you to be worthy of our great allies in the East, who fight desperately and fearlessly. If only I could, I would be the first to kneel before these people. I ask you, my dear Americans, help these people, pray for them. Remember that they die for you and me too. These are great people!» (Franklin Delano Roosevelt, addressing the American people, November 23, 1942.)

On September 12, 1941, the Presidential Council for Control of the Organization of Military Assistance officially registered the American Society for Relief to Russia, called the Committee " Help for Russia in the war"(Russian War Relief). The council included prominent bankers, industrialists, philanthropists, as well as representatives of the Russian diaspora. Among those who expressed support for the committee were Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin, Leon Feuchtwanger, Robert Oppenheimer, John von Neumann.

One of the Committee's propaganda posters

Already in 1942, the Committee became a large public organization with an extensive network of various sectors and divisions: regional (states, cities), women's, youth, religious (Jewish, Orthodox, Baptist, etc.), national (Russian, Jewish, Armenian and etc.). He had his own production plants, workshops, and warehouses. A particularly important role was assigned to the public relations sector, whose tasks included propaganda and agitation work. American citizens of all social classes donated millions of dollars to the Committee to purchase food, medicine, clothing, equipment and basic necessities. Parcels from the USA went to Soviet orphanages, schools, collective farms, and hospitals. These parcels contained letters from ordinary Americans expressing faith in victory. More than 2 million American families took part in the large-scale “Letter to Russia” campaign.

Postcard from an American from Kansas to the Soviet Union

When difficulties arose in purchasing clothing, shoes, textile products and other items on the US domestic market due to the lack of these goods in warehouses, the Committee decided to appeal to ordinary Americans to “ Share your clothes with a Russian ally!" The movement under this slogan became popular and widespread. The collection of clothes, shoes, and various household items took place throughout the country. Special points were organized for collecting and sorting collected items. Most of them turned out to be practically new, and the rejection rate was small. The Americans worked at these reception centers for free, and the drivers transported goods for free in their free time.

The last major charitable action of the society was the collection and shipment of English-language, mostly fiction, literature to the Soviet Union in order to at least partially compensate for the destruction by the Nazis of 12 thousand libraries and more than 20 million books on the territory of the USSR. It was planned to send 1 million volumes to the Soviet Union. The book collection campaign was unprecedented in scale. It was attended by schoolchildren, students, housewives, writers, scientists, politicians, and even President Truman himself, who donated a 40-volume collected works of George Washington to be sent to Russia. Books were collected by schools, universities, publishing houses, church communities, and libraries. The Library of Congress allocated 10 thousand volumes.

The book was transferred from New York to Karelia as part of the Committee’s activities

The Committee “Help to Russia in the War” did not relate to Lend-Lease supplies, but was a broad public initiative. But Kiselyov, naturally, won’t tell you anything about this.

American humanitarian aid to Russia in the early 90s.

The collapse of the Soviet Union naturally affected the ordinary citizen's plate. The administrative economy has died out, and the market economy has not yet been launched. The counters in Russian cities were empty, there was practically no normal quality food. And at this difficult moment, the restless insidious Pindos Americans, together with the Nazis and Germans, decided to feed the Russian people! Outrageous!

These were the C-17 military aircraft that sent food to needy post-Soviet countries

In 1991 alone, 241 thousand tons of food were supplied free of charge. In addition, preferential loans were allocated for the purchase of grain from the United States at prices below market prices.

In 1992, the Americans organized Operation Provide Hope. Until the early 2000s, military transport aircraft delivered humanitarian aid to various CIS cities. Minsk was also affected by this program.

Russia and Germany provided great assistance. Across Europe, non-governmental organizations collected packages for Russia.

Unloading foreign aid

While all sorts of Putins were making money by smuggling metals, and the Girkins were fighting in Transnistria, the West was trying to feed the hungry citizens of the Russian Federation. But Russia Today will not show this.

American aid 2020?

So we want to reassure all the racists. You can continue to go crazy, collapse the ruble, destroy the economy, grow fecal stalagmites, threaten the world with nuclear ash and drop your own bombers on Voronezh. They will still send you a jar of stew and an “I Love New-York” T-shirt. This is not the first time to save the bad.

In contact with

Some say that there was no famine, some say that there was, but not like this and not for such a long time. There is debate about its causes and consequences. Let's continue this topic by discussing another, rarely mentioned story.

At the beginning of the post you see Aivazovsky’s painting “Distribution of Food”, painted by the artist in 1892. On the Russian troika, loaded with American food, stands a peasant, proudly raising the American flag above his head. The film is dedicated to the American humanitarian campaign of 1891-1892 to help starving Russia.

The future Emperor of Russia Nicholas II said: “We are all deeply touched that ships full of food are coming to us from America.” The resolution, prepared by prominent representatives of the Russian public, read, in part: “By sending bread to the Russian people in times of hardship and need, the United States of America is showing a most moving example of fraternal feelings.”

Here's what we know about it in more detail...

I.K. Aivazovsky. ""The arrival of the steamship "Missouri" with bread to Russia", 1892.

In April 1892, American ships loaded with wheat and corn flour arrived at the Baltic ports of Liepaja and Riga. In Russia they were eagerly awaited, since for almost a year the empire had been suffering from famine caused by crop failure

The authorities did not immediately agree to the offer of help from US philanthropists. There were rumors that the then Russian Emperor Alexander III commented on the food situation in the country as follows: “I have no starving people, only those affected by crop failure.”

However, the American public persuaded St. Petersburg to accept humanitarian aid. Farmers in the states of Philadelphia, Minnesota, Iowa and Nebraska collected about 5 thousand tons of flour and sent it with their own money - the amount of assistance amounted to about $1 million - to distant Russia. Some of these funds also went towards regular financial assistance. In addition, American public and private companies offered long-term loans worth $75 million to Russian farmers.

Aivazovsky wrote two paintings on this topic - Food Distribution and Relief Ship. And he donated both to the Washington Corcoran Gallery. It is unknown whether he witnessed the scene of the arrival of bread from the United States to the Russian village depicted in the first painting. However, the atmosphere in the picture of universal gratitude to the American people in that hungry year is very noticeable.

“Unexpected” disaster

“The autumn of 1890 was dry,” wrote Dmitry Natsky, a lawyer from the Russian city of Yelets, located near Lipetsk, in his memoirs. “Everyone was waiting for rain, they were afraid to sow winter crops in dry soil and, without waiting, they began to sow in the second half of September.” .

He goes on to point out that what was sown almost never came up anywhere. After all, the winter had little snow, with the first warmth of spring the snow quickly melted away, and the dry soil was not saturated with moisture. “ There was a terrible drought until May 25th. On the night of the 25th, I heard the babbling of streams outside and was very happy. The next morning it turned out that it was not rain, but snow, it became very cold, and the snow melted only the next day, but it was too late. And the threat of crop failure became real,” Natsky continued to recall. He also pointed out that they ended up harvesting a very poor rye harvest.

Drought was widespread in the European part of Russia. The writer Vladimir Korolenko described this disaster that befell the Nizhny Novgorod province in the following way: “The clergy with prayers passed through the drying fields every now and then, icons were raised, and clouds stretched across the hot sky, waterless and stingy. From the Nizhny Novgorod mountains the lights and smoke of fires were constantly visible in the Volga region. The forests burned all summer, caught fire on their own”.

The previous few years were also poor harvests. In Russia, for such cases, since the time of Catherine II, there has been a system of assistance to peasants. She was involved in the organization of so-called local food stores. These were ordinary warehouses in which grain was stored for future use. In lean years, the regional administration lent grain from them to the peasants.

At the same time, by the end of the 19th century, the Russian government got used to constant cash receipts from grain exports. In good years, more than half of the harvest was sold to Europe, and the treasury received more than 300 million rubles annually.

In the spring of 1891, Alexey Ermolov, director of the non-salary collections department, wrote a note to Finance Minister Ivan Vyshnegradsky, warning about the threat of famine. The government conducted an audit of food stores. The results were frightening: in 50 provinces they were filled by 30% of normal, and in 16 regions where the harvest was the lowest - by 14%.

However, Vyshnegradsky stated: “ We won’t eat it ourselves, we’ll export it" The export of grain continued throughout the summer months. That year, Russia sold almost 3.5 million tons of bread.

When it became clear that the situation was truly critical, the government ordered a ban on grain exports. But the ban lasted only ten months: large landowners and businessmen, who had already bought up grain for export abroad, became indignant, and the authorities followed their lead.

The following year, when famine was already raging in the empire, the Russians sold even more grain to Europe - 6.6 million tons.

Meanwhile, the Americans, having heard about the enormous famine in Russia, collected bread for the starving. Not knowing that grain traders' warehouses are filled with export wheat.

The famous agronomist and publicist Alexander Nikolaevich Engelhardt wrote about what the export of grain meant for the Russian peasantry:

« When last year everyone was rejoicing, rejoicing that there was a bad harvest abroad, that the demand for bread was high, that prices were rising, that exports were increasing, only the men were not happy, they looked askance at the sending of grain to the Germans... We do not sell bread out of excess, that We sell abroad our daily bread, the bread necessary for our own food.

We send wheat, good clean rye abroad, to the Germans, who will not eat any rubbish. We burn the best, clean rye for wine, but the worst rye, with fluff, fire, calico and all sorts of waste obtained from cleaning rye for distilleries - this is what a man eats. But not only does the man eat the worst bread, he is also malnourished. If there is enough bread in the villages, they eat three times; there has become a derogation in the bread, the bread is short - they eat it twice, they lean more on the spring, potatoes, and hemp seed are added to the bread. Of course, the stomach is full, but bad food causes people to lose weight and get sick, the boys grow tighter, just like what happens to poorly kept cattle...

Do the children of a Russian farmer have the food they need? No, no and NO. Children eat worse than calves from an owner who has good livestock. The mortality rate of children is much higher than the mortality rate of calves, and if the mortality rate of calves for an owner with good livestock was as high as the mortality rate for children of a peasant, it would be impossible to manage it. Do we want to compete with the Americans when our children don’t even have white bread for their pacifier? If mothers ate better, if our wheat, which the German eats, stayed at home, then children would grow better and there would not be such mortality, all this typhus, scarlet fever, and diphtheria would not be rampant. By selling our wheat to the German, we are selling our blood, i.e. peasant children."

It was not only traders who ignored the famine; at first the authorities did not recognize that there was a real disaster in the country. Prince Vladimir Obolensky, a Russian philanthropist and publisher, wrote about this: “ Censorship began to erase the words hunger, hungry, starving from newspaper columns. Correspondence that was banned in newspapers circulated from hand to hand in the form of illegal leaflets, private letters from starving provinces were carefully copied and distributed”.

Chronic malnutrition was supplemented by diseases, which, given the then existing level of medicine in the empire, turned into a real pestilence. Sociologist Vladimir Pokrovsky estimated that by the summer of 1892 at least 400 thousand people had died due to famine. This is despite the fact that in villages, records of the dead were not always kept.

On November 20, 1891, William Edgar, an American publisher and philanthropist from Minneapolis, who owned the then quite influential Northwestern Miller magazine, sent a telegram to the Russian embassy. From his European correspondents he learned that there was a real humanitarian catastrophe in Russia. Edgar proposed organizing a collection of funds and grain for a country in distress. And he asked Ambassador Kirill Struve to find out from the Tsar: would he accept such help?

A week later, without receiving any response, the publisher sent a letter with the same content. The embassy responded a week later: “ The Russian government accepts your proposal with gratitude”.

Sociologist Vladimir Pokrovsky estimated that at least 400 thousand people died due to famine by the summer of 1892

That same day, Northwestern Miller issued a fiery appeal. “ There is so much grain and flour in our country that this food is about to paralyze the transport system. We have so much wheat that we won't be able to eat it all. At the same time, the most mangy dogs roaming the streets of American cities eat better than Russian peasants”.

Edgar sent letters to 5 thousand grain traders in the eastern states. He reminded his fellow citizens that at one time Russia helped the United States a lot. In 1862-63, during the Civil War, a distant empire sent two military squadrons to the American coast. Then there was a real threat that British and French troops would come to the aid of the slave-owning south, with which the industrial one was at war. Russian ships then stood in American waters for seven months - and Paris and London did not dare to get involved in a conflict with Russia as well. This helped the northern states win that war.

Almost everyone to whom he sent letters responded to William Edgar's call. The fundraising movement for Russia has spread throughout the United States. The New York Symphony Orchestra gave benefit concerts. Opera performers picked up the baton. As a result, the artists alone raised $77 thousand for the distant empire.

To provide humanitarian assistance in the United States, a famine relief committee (Russian Famine Relief Committee of the United States) was organized. The committee's funding came primarily from public funds. The so-called “Famine Fleet” was formed. The first ship, the Indiana, which delivered 1,900 tons of food, arrived on March 16, 1892 at the port of Liepaja on the Baltic Sea. The second ship, the Missouri, delivered 2,500 tons of grain and cornmeal, arriving there on April 4, 1892. In May 1892, another ship arrived in Riga. Additional ships arrived in June and July 1892. The total cost of humanitarian aid provided by the United States in 1891-1892 is estimated at about $1,000,000 (US dollars).

The Americans spent three months delivering humanitarian flour. Edgar himself swam to Berlin, and traveled to St. Petersburg by train. At the border he suffered his first shock. “The Russian customs officers were so strict that I felt like a rat in a trap,” wrote the traveler. Edgar was struck by the Russian capital - its luxury did not really correspond to the starving country. Moreover, they greeted him according to local tradition with bread and salt in a silver salt shaker.

Then the American philanthropist traveled through famine-stricken regions. It was there that he saw the real Russia. “ In one village I watched a woman prepare dinner for her family. Some kind of green herb was boiling in a pot, to which the hostess threw in a couple of handfuls of flour and added half a glass of milk”, Edgar later wrote in his journal.

He was also struck by the scenes of the distribution of humanitarian aid he had brought. One distribution official allowed hungry peasants to take as much as they could carry. “ Exhausted people shouldered a sack of flour and, barely moving their legs, dragged it to their families.“, Edgar reported.

There were also some oddities familiar to Russia, which were incomprehensible to an American. Already in Liepaja, part of the humanitarian aid disappeared without a trace. Edgar was warned that local merchants would resort to any tricks for profit. A month earlier, the government purchased 300 thousand pounds of grain. It turned out that almost all of it was mixed with soil and was therefore unsuitable for consumption.

There is also this opinion about this entire campaign: The role of the USA is insignificant. The fact is that the United States actually received stable harvests in those years, but in order not to bring down the price, the capitalists burned the grain, it was more profitable than selling it at a low price. In total, there were 5 ships from the United States of approximately 2000 tons. They came in the spring at the very end of the famine. And basically this grain was used for spring sowing, and not for food.

You can also read the article - Debunking the myth of famine in Russia in 1891-1911 , where it is argued that the famine was caused only by natural disasters, the state actively solved the problems of hunger and the “hunger” not only dealt a blow to the peasant economy and the country’s economy, but also stimulated them: the production of potatoes, industrial and other non-cereal crops increased sharply, Livestock farming developed (for example, new steppe breeds of horses appeared), the transition to intensive forms of farming accelerated, and finally, the “Tsar Famine” of 1891-92 was followed by a real boom in railway construction.

P.S. By the way, these two paintings by Aivazovsky were sold at Sotheby’s auction in 2008 for $2.4 million. The buyers, private individuals, are unknown.

sources

http://www.situation.ru/app/j_art_164.htm

http://a.kras.cc/2015/09/blog-post_97.html

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%93%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4_%D0%B2_%D0%A0%D0%BE%D1%81%D1 %81%D0%B8%D0%B8_(1891%E2%80%941892)

http://maxpark.com/user/20074761/content/531271

http://www.rbc.ru/opinions/society/13/03/2016/56e2a7739a7947f8afe48a05

http://www.xliby.ru/istorija/_golodomor_na_rusi/p8.php

Here is another quite interesting topic: and

I.K. Aivazovsky. ""The arrival of the steamship "Missouri" with bread to Russia", 1892.

Due to the severe harvest failure of 1891, which engulfed the south of Russia and the Volga region, famine began across a vast territory of the country, aggravated by the continued export of Russian wheat abroad. The Russian government, however, denied the existence of a famine, saying the West was exaggerating the severity of the situation. Officially, American humanitarian aid to Russia was offered by the US diplomatic mission in St. Petersburg in mid-November and accepted by the Russian government on December 4, 1891. Grand Duke Nicholas, the future Emperor of Russia, was appointed head of the special committee for famine relief; The coordinators of American assistance on the Russian side are the Minister of the Household I.I. Vorontsov-Dashkov and A.A. Bobrinsky.

The campaign to help the starving Russians was waged in the United States under the slogan of the need to repay Russia kindly for the support provided during the American Civil War. The US Committee for Russian Famine Relief was created in the United States ( Russian Famine Relief Committee of the United States), who received the moral support of official American authorities, although assistance was provided primarily through funds raised by American citizens and private organizations.

The transport ship Indiana, equipped by the Philadelphia public Indiana) with a cargo of food weighing a total of 1900 tons arrived at the Baltic port of Libau (Liepaja) on March 16, 1892. The second ship, Missouri, equipped by residents of the states of Minnesota, Iowa and Nebraska ( Missouri) delivered a cargo of wheat and corn flour with a total weight of 2500 tons to Libau on April 4, 1892. In May, a ship equipped with Philadelphians arrived at the port of Riga with humanitarian cargo, and in June - a ship equipped with the American Red Cross in Washington, in July - another from New York.

A charity concert of opera singers and the New York Symphony Orchestra, organized on March 12 in New York, added 7 thousand dollars to the 40 thousand previously collected for the benefit of the hungry in Russia. By mid-April 1892, the American mission in St. Petersburg received 77 thousand dollars from various US cities to fund the famine relief in Russia. The total cost of services provided to Russia in 1891-92. private and public humanitarian assistance (including transportation costs) was estimated at $1 million. According to information from American sources, the US government (Department of the Interior) provided financial assistance to individual Russian provinces in the form of loans totaling $75 million.

The future Emperor of Russia Nicholas II said: “We are all deeply touched that ships full of food are coming to us from America.” The resolution, prepared by prominent representatives of the Russian public, read, in part: “By sending bread to the Russian people in times of hardship and need, the United States of America is showing a most moving example of fraternal feelings.”

I.K. Aivazovsky, “Distribution of Food”. 1892

P.S. “Ivans, who do not remember their kinship, are usually called people who are unprincipled, ungrateful, and who easily forget the good they have done.”

From the dictionary of popular words and expressions