Prince Yaroslav the Wise. His children and dynastic connections

Dynastic marriages were concluded with the goal of uniting two dynasties and thereby connecting the two countries with strong ties to each other. When such marriages were concluded, relations between countries improved.

To organize a dynastic marriage, both parties had to profess the same religion, but if they professed different religions, then the bride had to accept the religion of her future husband.

Russian princes always sought to strengthen the authority of Rus' in Europe, for this purpose they entered into dynastic marriages with European royal houses.

Prince Yaroslav the Wise (no wonder he received such a nickname!), ruling at the beginning of the 11th century, was married to the Swedish princess Ingigerda, who received the name Irina in baptism. Irina, the daughter of the Norwegian king Olaf, brought the city of Staraya Ladoga as a dowry.

One of Yaroslav's sons, Vsevolod, married the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Monomakh.

They had a son, Vladimir, who went down in history as the Grand Duke of Kiev Vladimir Monomakh, because he added the name of his maternal grandfather to his name. The word "monomakh" translated from Greek means "combatant". Thus, through the female line, Vladimir could be considered the direct heir to the throne of Byzantium.

It is believed that Constantine Monomakh gave his grandson Vladimir the well-known Monomakh cap as a sign that Vladimir contributed to the further advancement of the Orthodox faith in Rus'. This headdress was supposed to symbolize the continuity of power of Russian rulers from the Byzantine emperors. What kind of Monomakh hat is this?

This cap, a symbol of state power, is an antique piece of jewelry consisting of eight gold plates set with precious stones and weighs 498 grams. It is kept in the Kremlin Armory.

Kings wore Monomakh's hat only on the day of their royal crowning. The last Russian tsar to be crowned king with the cap of Monomakh was Ivan V, the elder brother of Peter the Great.

In turn, Vladimir Monomakh also continued the traditions of his grandfather and married the English princess Gita.

But let's return to Yaroslav the Wise. His other son Izyaslav married the sister of the Polish king Casimir Gertrude. Russian sources repeatedly mention the wife of the Kyiv prince Izyaslav, “Lyakhovitsa”. At baptism she received the name Elena, according to other sources Olisava (Elizabeth).

The princess was very educated, she was fluent in four languages - Polish, German, Russian and Latin.

Prince Izyaslav listened to the words of his wife, she gave him wise political advice. For example, when he wanted to expel the monks from the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery, the princess stood up for them, citing the fact that unrest began in her homeland in Poland after the “Monnets” were removed from there.

With this in mind, Izyaslav allocated land for the expansion of the Kiev-Pechersk Monastery and founded the Dimitrovsky Monastery in Kyiv,

How did historians learn about Elena-Olisava’s active participation in governing the principality? After her, a Latin manuscript that belonged to her was preserved - the famous “Gertrude's Prayer Book”, with two miniatures depicting Gertrude herself, her son Yaropolk and his wife Irina.

In general, “Gertrude’s Prayer Book” is a unique monument in all respects. Currently, this prayer book is kept in the National Archaeological Museum of the northern Italian city of Cividale.

Continuing to talk about the political activities of Yaroslav the Wise, one cannot help but recall the fact that in order to strengthen the alliance with the Poles, the prince gave his sister Dobrogneva, who received the name Maria in Catholic baptism, as a wife to the Polish king Casimir.

Western historians report that the dowry received by Mary was so large that one could speak of “the enrichment of the kingdom thanks to such a brilliant marriage and the strengthening of its good neighborliness.” Maria Dobrogneva, together with her sons, also carried out state affairs.

In addition to his sons, Yaroslav the Wise had three daughters.

Yaroslav's eldest daughter Elizabeth, baptized Ellispva, was married to the Norwegian prince Harold the Terrible.

The prince met Elizabeth while serving at the court of Yaroslav the Wise. However, his attempt to immediately get the princess as his wife was unsuccessful: Yaroslav refused him, since the prince had neither wealth nor the throne. The Viking, having received a refusal, went to seek his fortune around the world in order to either forget the beautiful princess or become worthy of her hand and heart. He became famous for his military exploits in Italy and Sicily and acquired fame and enormous wealth, which he constantly sent to the court of Prince Yaroslav, proving that he was worthy of being his son-in-law.

The Norwegian prince turned out to be not only a Viking hero, but also a poet. In the best traditions of knightly poetry, he composed a song of 16 stanzas in honor of his beloved, each of which ended with the phrase: “Only a Russian girl in a golden hryvnia neglects me.” This song was repeatedly translated by Russian poets, in particular A.K. Tolstoy.

In 1035, Elizabeth was given to him as his wife, and Harold returned to Norway. However, he soon died in internecine wars. After his death, Elizabeth married the Danish king.

Yaroslav the Wise gave his second daughter Anastasia as a wife to the Hungarian King Andrew.

The name of Anastasia-Agmunda (she received this name upon conversion to the Catholic faith) is associated with the founding of two Orthodox monasteries - in Vysehrad and Tormov.

After the death of King Andrew, a political struggle for power began between his son and his opponents. Anastasia was forced to flee persecution to Germany. What happened to her in the future is not indicated in historical documents; the thread of her fate is lost.

The most interesting fate of the youngest and beloved daughter Anna, who was married to the French king Henry I.

The widowed French king Henry I of the Capetian dynasty heard about the Kyiv beauty and decided to marry her. Anna was beautiful (according to legend, she had “golden” hair), smart and received a good education for that time, she read a lot, because Yaroslav the Wise had the largest library of that time, and knew several foreign languages. At the time of the matchmaking she was about 17 years old.

Heinrich was not young, at over forty years old he was obese and always gloomy, besides, he was illiterate and signed himself with a cross. He had difficulty holding the reins of power and hoped to strengthen the country's prestige through a matrimonial connection with a strong state.

The main motive for this choice of the French king Henry I was the desire to have a strong, healthy heir. The second motive was that his ancestors from the Capetian house were related by blood to all neighboring monarchs, and the church forbade marriages between relatives. So fate destined Anna Yaroslavna to continue the royal power of the French Capetians.

Henry sent the first wedding embassy to distant Rus'. The ambassadors were instructed to obtain consent to marry Anna. But Yaroslav the Wise refused the first embassy; he wanted to give Anna to the German ruler Henry III in order to strengthen allied relations with the countries of the North-West.

However, Henry I of Capet was persistent, and a year later the ambassadors of the King of France went to Kyiv for the second time for a Russian bride, Princess Anna Yaroslavna. Yaroslav the Wise was forced to agree.

The matchmakers presented Yaroslav with rich gifts from Henry the First: Flemish brocade, Reims cloth, Orleans lace, the famous Toledo sword. Yaroslav also did not disappoint and gave furs, vodka, caviar, and numerous jewelry for his daughter, among which was the famous gem - the hyacinth of St. Denis. To these gifts Anna herself added books and several icons, including her most beloved, depicting Saints Gleb and Boris, the founders of their family. She did not forget about the ancient Gospel, written in Cyrillic and Glagolitic.

Anna Yaroslavna traveled for several months to France through Krakow, Prague and Regensburg. What did the young girl think, knowing that she was going to her husband, whom she had never seen, that he was ugly and not young? What kind of love could she dream of? After all, from childhood she was prepared to be a queen in a foreign country with foreign rituals and language. And all of Yaroslav’s daughters were ready for this. The prestige of the country was higher than personal feelings.

On May 14, 1051, Anna Yaroslavna solemnly arrived in France. A jubilant crowd in the ancient city of Reims came to greet their future queen. Anna was an excellent rider and proudly rode her horse into this unfamiliar country. Henry I went to meet his bride in Reims, where their wedding took place.

Anna Yaroslavna refused to swear in the Latin Bible and took an oath in the ancient Gospel, written in Cyrillic and Glagolitic, which she brought with her from Kyiv (it was already mentioned earlier).

Subsequently, according to tradition, the French kings, when anointing, made a vow to God on this Gospel, and since the Slavic alphabet was completely unfamiliar to them, they mistook it for some unknown magical language.

In July 1717, when Emperor Peter the Great visited Reims, he was shown this Gospel and explained that none of the people knew this “magic language.” Imagine the surprise of the French when Peter began to fluently read it aloud!

Now this Gospel is kept in Paris.

In the future, Anna, as the wise daughter of her father, will accept Catholicism.

Anna took part in governing the state - on documents of that time, next to her husband’s signature, her signature is also found. On state acts and charters you can read: “With the consent of my wife Anna,” “In the presence of Queen Anne.”

However, the first years of her life in this country were far from easy. Being a queen, she simply had no right to make the slightest mistake. In letters to her father, Anna Yaroslavna wrote that Paris is gloomy and ugly, like a village where there are no palaces and cathedrals, which Kyiv was rich in: “What a barbaric country have you sent me to. The houses here are gloomy, the churches are ugly.” Indeed, this was not the Paris that “you can see and die,” as they say now. It was Paris of the 11th century, a dirty village, and all the famous buildings appeared in it only after the 16th century.

Moreover, in Paris they did not use the bathhouse that Anna was used to, and Henry himself generally washed very rarely, about once a year. It’s hard to believe now, but the morals of that time really were like that.

The food was also different from what Anna was used to. In Rus' they ate porridge, pies, soups, drank honey drinks and decoctions, and in Europe at that time they ate lightly fried meat, washing it down with sour wine. Of course, she had to get used to a completely different way of life.

Moreover, Anna was hardly happy as a woman. Scientists have different opinions on this matter, and here's why: some of Queen Anne's fans believe that the king had homosexual tendencies, and he was absolutely indifferent to his young and beautiful wife, from whom he primarily expected an heir. Anna, apparently, also did not experience any other feelings for Henry, except for duty and respect.

The marriage of Anna and Henry lasted about nine years, then Henry died. Three sons were born from this marriage. The eldest Prince Philip became King of France at the age of 8.

The Greek-Byzantine name Philip was not used in Western Europe at that time. Anna named her eldest son by this name, and it later became widespread. It was worn by five more French kings; one can say that with Anna’s light hand this name became a family name in other European dynasties.

Anna achieved real recognition by continuing her husband's policy aimed at strengthening royal power in France. She managed to inspire respect for herself, showing herself to be a brave, persistent, selfless ruler, striving for the good of her kingdom.

At 30, she married again to Count Raoul de Valois. Apparently it was true love.

Anna, like Raoul, sacrificed a lot for this love. She alienated herself from her son the king, lost the title of queen, and along with the title she was deprived of the right to rule the kingdom. She preferred love to a high title, and this can be understood.

Where Anna's grave is located is unknown. Some believe that in France, but during the French Revolution her grave was plundered and lost. Others believe that she returned to Russia, but this is most likely just a legend. The most important thing is that Queen Anne is still honored and remembered in France.

The political steps of the sons, daughters and sisters of the powerful Yaroslav the Wise are worthy of remaining in our memory for the fact that they made a feasible contribution to strengthening the international prestige of their Motherland, their dynastic marriages contributed to the strengthening of friendly relations with the states of Western Europe and thereby strengthened the position of Rus' in the international arena.

The story about Anna Yaroslavna involuntarily echoes the story about another Anna, but one that happened 500 years after the above events.

We all know the story of Anne of Austria, Queen of France and wife of King Louis XIII thanks to Dumas' novel The Three Musketeers. Meanwhile, this woman played an extraordinary role in the events of the turbulent 17th century.

Anne was a Spanish princess belonging to the Habsburg dynasty. As is expected in arranged marriages, at the age of three she was betrothed to the French Dauphin Louis.

At the age of fourteen, Anna Maria was taken to Paris to marry the young King Louis XIII.

Anna was exhausted by curiosity as to what her fiancé would turn out to be - handsome or ugly, good or evil. But this did not play any role, since its task was to reconcile the long-warring dynasties of the Habsburgs and the French Bourbons.

Born in September 1601, Anna’s life, like that of other Spanish princesses, was subject to a strict routine: early rise, prayer, breakfast, then hours of study. Young infantas learned sewing, dancing and writing, crammed the sacred history and genealogy of the reigning dynasty. This was followed by a gala dinner, a nap, then games or chatting with the ladies-in-waiting (each princess had her own staff of courtiers). Then again long prayers and going to bed - exactly at ten in the evening. As you can see, Anna was raised in Spanish strictness.

The French court where Louis grew up was completely different from the Spanish one. Laughter and dirty jokes were often heard here, adultery was discussed, and the king and queen almost openly cheated on each other. They paid no attention to Louis at all, and his mother, Maria de Medici, visited him only to slap him in the face or whip him with rods for any offense. It is no wonder that he grew up withdrawn and obsessed with many complexes.

Louis also knew from childhood that Anna was destined for his wife, but already in advance he was prejudiced towards his future wife. Already at the age of three he spoke about her like this: “She will sleep with me and give birth to a child for me.” And then he frowned: “No, I don’t want her. She’s Spanish, and the Spaniards are our enemies.”

When he first saw Anna, she seemed so beautiful to Louis that he could not say a word to her. Anna was truly beautiful. From her Austrian ancestors she inherited blond hair and skin; only her black, burning eyes betrayed her Spanish origin.

In the evening, at the official engagement banquet, Louis was embarrassed and dumb as a fish.

In Paris, after the wedding, a marriage bed awaited the newlyweds, but Louis was so frightened that his mother had to almost force him into the bedroom where Anna was waiting. In addition to the mother, there were two maids present who instructed the young people what and how to do. In the morning, a crowd of courtiers was presented with evidence that “the marriage had taken place properly.”

It is no wonder that such actions led to the fact that Louis was completely discouraged from communicating with women. They say that after his wedding night he “did not look into his wife’s bedroom” for four whole years. The desired heir was never conceived - neither on the first night, nor for the next ten years.

Seeing the debauchery at court, Louis began to hate women and consider them insidious temptresses.

He forbade not only his wife, but also all the ladies of the court, from wearing too revealing necklines and tight dresses, so that their appearance would not distract him and his subjects from pious thoughts.

But the king behaved very affectionately with the handsome young pages, which gave rise to a wave of rumors in Paris. Louis spent whole days with them falconry, completely forgetting about his wife, and the young queen led a boring life in the Louvre, she yearned for male attention, which she was still deprived of. It took the efforts of the Pope and the Spanish ambassador for Louis to appear in his wife’s bedroom again, but the “honeymoon” was short-lived this time too. And yet, the queen did not want to cheat on her husband; her Spanish upbringing was reflected in her.

And then Cardinal Richelieu suddenly became involved in the “education of feelings” of the queen. Despite his rank, he did not shy away from women. Now he himself decided to win the heart of Anna of Austria.

The Cardinal hopes to do what Louis failed - to conceive an heir and elevate him to the throne of France. It is more likely that he simply wanted to keep the queen “under the hood”, preventing her from getting involved in any conspiracy. It cannot be ruled out that Richelieu was simply carried away by Anna, whose beauty had reached its peak; she was 24 years old, he was almost forty.

But the cardinal’s masculine charms left her indifferent. Perhaps her Spanish upbringing again played a role - Anna perceived men in robes only as servants of the Lord.

And yet love visited the queen’s heart. This happened when the English envoy, 33-year-old George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, arrived in Paris.

Thanks to literature and films, we imagine the Duke of Buckingham as a kind of English macho who appeared on the French horizon.

In fact, he came from an impoverished family. The Duke's wealth and title came to him thanks to the generosity of the aging King of England, James I, whose young Buckingham was his lover, who even agreed to portray a jester at court for the sake of titles and wealth. In fact, Buckingham did not have homosexual inclinations.

Dying, the king bequeathed Buckingham to his son Charles as his chief adviser and lover, but the young people were truly connected by male friendship, so Buckingham did not become Charles’s lover.

At his request, the Duke came to France to woo the sister of Louis XIII, Princess Henrietta, to the new monarch.

As soon as Buckingham saw Anna, he lost his head. His masculinity surged within him, which he could not express under King James. The Duke spent three years of his life trying to win Anna's favor. Apparently, Anna did not deprive Buckingham of her attention, since she had long yearned for male attention. From the novels of Alexandre Dumas and films we know what a passionate love it was!

There was also a story with pendants. Several contemporaries speak about them in their memoirs, including the queen’s friend, the famous philosopher Francois de La Rochefoucauld.

D'Artagnan also existed. True, he did not take part in the mad rush to return the pendants to France, as we know from Dumas’ novel - at that time this son of a Gascon nobleman was only five years old.

Why was the cardinal so eager to annoy the queen? Of course, one of the reasons was his wounded pride as a rejected man. And of course, he was again afraid that Anna would conspire with the enemies of France. Therefore, he tried to quarrel between her and her husband. He succeeded: despite the return of the pendants, Louis was completely disappointed in his wife. She turned out to be not only an immoral person, but also a traitor, ready to exchange him for some foreigner! Buckingham was banned from entering France, and the queen was locked in the palace.

Soon the Duke of Buckingham died at the hands of an officer named Felton, who stabbed him with a sword. Many considered the killer to be the cardinal's spy, but no evidence of this was ever found.

Thus ended the tragic love of Anne of Austria and the Duke of Buckingham, in memory of which only the story of diamond pendants remains.

Anna of Austria lived in an atmosphere of conspiracies and intrigues. Despite this dynastic marriage, Spain continued to fight with France, and in order to avoid accusations of disloyalty, Anna did not communicate with her compatriots at all for many years and had already begun to forget her native language.

However, when she wrote a completely harmless letter to the Spanish ambassador in Madrid, it immediately fell into the hands of Cardinal Richelieu and was handed over to the king as proof of a new conspiracy. But this time Anna found an intercessor - the young nun Louise de Lafayette, with whom the king began a sublime “spiritual romance.” She reproached Louis for cruelty towards his wife and recalled that it was his fault that France was still left without an heir.

This suggestion was enough for the king to spend the night in the Louvre in December 1637, and after the allotted time, the queen had a son - the future “Sun King” Louis XIV. Two years later, his brother, Duke Philippe of Orleans, was born. Of course, the story with the “iron mask” is just another invention of novelists: there were no twins, sons were born one after another. However, many historians doubt that the father of both children was actually Louis XIII.

Many candidates were proposed for this role, including Richelieu, Mazarin and even Rochefort - that same scoundrel from The Three Musketeers. The king's brother Gaston d'Orléans, who shared with Anna a hatred of Richelieu, was not excluded. It is not unreasonable to assume that the cardinal personally selected and sent some strong young nobleman to the yearning queen to ensure the appearance of the Dauphin. And in the French film "The Three Musketeers" the father of the king was D'Artagnan himself.

The name of the real father of the “Sun King” became another mystery of Anna and history. She lived for 65 years and died of breast cancer, taking with her all the secrets.

Anna of Austria was neither cruel nor selfish. She cared in her own way about the good of the state and yet had the most vague idea about this good. She cannot be placed next to such great empresses as the English Elizabeth I or the Russian Catherine II.

Dynastic marriages were not always so unhappy. There are examples when spouses in such a marriage found love and happiness.

Over the years, films called "Sissi" were made about the romantic love of Elizabeth of Bavaria and Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria.

The life of Elizabeth, whom everyone called Sissy, in many ways remained a mystery, which after her death caused an avalanche of literary research with speculation and fantasies.

The story of her marriage was romantic. Franz Joseph was destined to marry Sissi's elder sister, Princess Helena, and the entire Bavarian family was invited to Austria for the "bride." At the end of a boring dinner, little Sissy fluttered into the room. Seeing her, Franz Joseph, who was already 23 years old, lost his head. He approached not the older sister, but the younger one and invited her to look at the horses. Returning from a walk, he announced to his mother that he was marrying, not Elena, but Princess Elizabeth. A few months later, on a ship strewn with flowers, the emperor took his young bride from Bavaria to Vienna along the Danube. Elizabeth experienced a similar love then.

Over the course of six years, she gave birth to two daughters, but after the difficult birth of her third child, the heir to the throne Rudolf, all feelings were cut off from the empress like a knife. Why this happened still remains a mystery.

Elizabeth leaves Vienna for a long time, away from her husband and children. She spends almost two years alone on the island of Madeira, then on Corfu. Although she returned to her husband, from then on she spent most of the year outside her empire. This suited her, but Franz Joseph was forced to accept it.

Elizabeth died in an unusual way, as she lived, as a result of a terrorist attack.

On September 9, 1898, Sissy arrived in Geneva. Tormented by a vague premonition, she decided to leave the next day by boat. Before landing, she managed to go to a music store, and then went on foot to the pier, which was about 100 meters away.

Just before the pier, a man suddenly ran across the street and, bending low, hit Elizabeth in the chest, as if with a fist. The empress fell, the man ran. Random passers-by chased him and soon caught him. It turned out to be the Italian anarchist Luccheni.

Already on board, when the ship began to depart, Elizabeth suddenly turned pale and began to fall to her knees. It turned out that the terrorist who attacked her pierced her heart with an ordinary triangular file 16 cm long. With such a terrible wound, she talked, moved and lived for about half an hour.

Shortly before this, Franz Joseph was also assassinated by a terrorist from Hungary, but he survived. In general, the emperor reigned for about 70 years. He was a very conservative person who did not recognize any technical innovations. In his entire life, he only rode once in a car, did not use an elevator, did not use a typewriter, and did not like the telephone.

Some historians point to the fatal circumstances that accompanied the reign of Franz Joseph. This is the loss of his wife and several heirs to the throne.

Franz Joseph's son and heir, Crown Prince Rudolf, a very talented but unbalanced man, committed suicide at the age of 30 in the Mayrling hunting lodge near Vienna. The tragedy remains a mystery to this day: the most common version is that Rudolph killed his mistress, 17-year-old Maria Vechera, with a revolver shot, and a few hours later he shot himself, so unsuccessfully that he blew off almost the entire top of his skull.

What caused the double murder? Crown Prince Rudolf was married to Princess Stephanie of Belgium, but the marriage was unsuccessful. He fell in love with the daughter of Baroness Evenings; naturally, he could not marry her. In his suicide letter to Stefania, he writes: “You will get rid of my presence. I calmly go towards death, because this is the only way I can save my name. Your loving husband Rudolf.”

There is not a word in this letter about the motives for death, only a short hint. On

what - on a gambling debt, unhappy love, the inability to live double

life? The same hint is repeated in other suicide letters from the prince. It turns out that it was suicide.

The Mayerling tragedy has become the subject of many works of art and films.

The second tragedy is the famous Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 by a Serbian high school student, a member of a terrorist organization. This event marked the beginning of the First World War.

Austria-Hungary ceased to exist two years after the death of Emperor Franz Joseph.

And yet, the love story of the Bavarian Princess Elisabeth, nicknamed Sissi, and the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph is an impeccable, well-selling brand. The love story of their son Rudolf and Maria Vechera is also often replicated. The Austrians know how to benefit from their history!

Here is another example of a successful dynastic marriage in Russia.

Princess Dagmar (her full name is Maria-Sofia-Frederica-Dagmar) from the Kingdom of Denmark has always been a desired bride for the rulers of many European countries, but she was given in marriage to the Russian Emperor Alexander III.

The decision was made by Alexander’s parents, and he had no choice but to agree to ask for Dagmar’s hand in marriage. “He bowed to necessity, to duty,” wrote S.D. Sheremetev, friend of the royal family. The fact is that Dagmar was supposed to marry his older brother Nikolai Alexandrovich, the future emperor, but he, having caught a cold, unexpectedly died from tuberculous meningitis and from improper treatment.

Dagmar also could not forget Nikolai, but agreed with her parents’ decision. Alexander was uncouth, poorly educated and unprepared for serious government activities, since he was never considered by his parents as a possible future emperor.

We remember that dynastic marriages are concluded without a hint of love.

When Princess Dagmar was escorted to the ship bound for Russia, the great storyteller Hans Christian Andersen could not hold back his tears when the princess, passing next to him, extended her hand in farewell. “Poor child!” he would write later. “There is a brilliant court in St. Petersburg and a wonderful royal family, but she is going to a foreign country, where there is a different people and religion, and there will be no one with her who surrounded her before.” But all the royal children are ready for this, knowing that their they must sacrifice their lives for the good of their country.

But everything turned out to be not so bad.

The young crown princess, who took the name Maria Feodorovna at Orthodox baptism, began her family and social life. She regularly gave birth to children (there were five of them, of course, the first-born was named Nikolai in honor of the deceased older brother Alexander and ex-fiancé Dagmar) and participated in social life. Everyone admired her intelligence, beauty, and manners. She steadfastly withstood hours-long receptions, loved balls and dancing “till you drop,” and the crown princess did not change her love of dancing even during periods of pregnancy, she was friendly and at the same time majestic with everyone.

Unlike his wife, Alexander the Third did not like balls and receptions; he was overweight and was afraid to seem funny while dancing. But he liked military training and competitions, where he showed the abilities of an excellent shooter.

In the photo of that time, Dagmar looks like a small, thin, graceful girl, and next to her is the healthy, huge, real Russian hero Alexander the Third. By the way, he was the largest of all the reigning emperors.

Dagmar spent time not only at balls. She was probably the only one of the wives of the ruling emperors who devoted much time to charity.

She skillfully managed the Russian Red Cross Society, shelters, hospitals, and women's schools, organizing surprise checks in hospitals, while literally looking into the plates of the sick, asking what they were fed and what kind of bed linen they had.

During the First World War, she organized hospitals, collected things and food for soldiers, often visited warships, and “rooted” for the development of Russian military aviation. She herself was a skillful and economical housewife: she did not disdain to peel potatoes with her own hands and darn her husband’s socks. This is evidenced by photographs depicting the august lady with a knife and a potato in her hands.

Alexander Alexandrovich was completely captivated by the kindness, sincerity and amazing femininity of his chosen one. He wrote in his diary that if you have such a wife, you can be calm and happy.

The Emperor always remained emphatically, to the point of asceticism, modest in everyday life, and there was no posture in this.

They lived together for 28 years and really fell in love with each other and were very sad when they had to part, so they tried to do this as little as possible and, while apart, wrote to each other every day. In his letters he called her "Minnie".

Although Alexander did not like his wife to interfere in state affairs, Maria Feodorovna still secretly guided her husband, since Alexander III did not have great abilities in leading the country, and was not averse to drinking, so it was up to his crowned wife to ensure that decorum was maintained.

Maria Feodorovna, oddly enough, hated the Germans and everything German from childhood. The choice of her eldest son, the heir of Nicholas II, who decided to marry a German princess, was a blow for her. She resisted this marriage for a long time and subsequently did not love her daughter-in-law. She considered Alexandra Fedorovna to be overly hysterical, incapable of the burdensome imperial duties, and, moreover, with bad taste.

After the son’s marriage, relations with his daughter-in-law did not go well at all: the two empresses were too different in character. Alexandra Feodorovna, constantly immersed in her complex experiences that were incomprehensible to her mother-in-law, seemed vulnerable and at the same time too cold and alienated.

At the beginning of 1894, Alexander III suddenly and seriously fell ill. Doctors diagnosed him with pneumonia. Having always given the impression of a man with powerful, even indestructible health, he literally melted before our eyes. All the famous doctors whom the royal family turned to for consultations could not establish the exact cause of the sharp deterioration in his health (as it turned out later, it was acute heart failure).

In addition, Alexander III himself really did not like to get sick and be treated; he simply ignored many of the recommendations of doctors. He began to experience severe swelling of his legs, shortness of breath and weakness, he became terribly thin, could not sleep or walk, and suffered terribly from acute pain in his chest. Maria Fedorovna transported him to Crimea, in the hope of the beneficial effects of the southern climate, but this did not help, and he soon died in the Livadia Palace. Having learned about this, Maria Fedorovna lost consciousness, so great was their love.

During these 13 years, while they jointly led the country, Russia lived without wars and upheavals, nevertheless having the highest political and military authority in Europe, although historians call this period “stagnation”.

After the revolution, Maria Feodorovna was not arrested along with the royal family. She was even allowed to say goodbye to her son Nicholas II, who had abdicated the throne, and leave for Crimea. There she received news of the death of her son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren. She was allowed to travel to her homeland, Denmark.

What else characterizes Maria Fedorovna as a noble person who loves Russia? This is that she took with her only a jewelry box when she emigrated, although she had at her disposal considerable wealth from the imperial dacha and a whole ship for exporting valuables.

Maria Feodorovna, whose maiden name was the Danish princess Dagmar, lived another seven years in her homeland in Copenhagen, in extreme poverty and loneliness. But until the end, she kept the box with her jewelry and believed that her son and grandchildren survived, and hoped to meet them.

Maria Fedorovna, despite her origin, was always considered to be originally Russian, therefore, at the insistence of the public, on September 28, 2006, her ashes were brought from Denmark and reburied in the Peter and Paul Cathedral of St. Petersburg.

As we reported earlier, Empress Maria Feodorovna was always against the marriage of her son Nicholas II and Princess Alix from the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt. Alexander III also knew about his son’s passion for his charming cousin Alix, but was not enthusiastic about an alliance with another German ruling house. Having concluded an alliance with France, he considered marrying his heir to one of the princesses of the House of Orleans.

Nicholas was in despair, but in the end his parents agreed to his marriage to Alix, and Nicholas II married her (her full name was Alix Victoria Elena Brigitte Louise Beatrice of Hesse-Darmstadt, at baptism she received the name Alexandra Fedorovna).

Although this marriage did not contribute to the improvement of Russian-German relations, the emperor loved Alexandra Fedorovna all his life. This is one of the few cases where royalty married “for love.”

The Hessian princess was raised in Great Britain by her grandmother, Queen Victoria. In mind, feelings and tastes she was more like an Englishwoman than a German. The daily language of the last emperor's family was English. Letters in English from Nicholas II to his Alix, filled with love and tenderness, have been preserved.

Nikolai Alexandrovich and Alexandra Fedorovna had 5 children: Princess Olga was born in 1895, Tatiana in 1897, Maria in 1898, Anastasia in 1901, and the heir to the throne, Tsarevich Alexei, was born in 1904.

After the revolution, the family was sent to Yekaterinburg. In July 1918, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, headed by Chairman Sverdlov, decided to execute the royal family. Lenin believed that “it is impossible to leave a living banner, especially in the current difficult conditions.”

Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra Feodorovna and their children remained together until the last minute, understanding what awaited them. On the night of July 16-17, 1918, the royal family, 3 servants and a doctor were shot in Ipatiev’s house. They did not part during life and did not part after death, their love went into eternity.

Thank God that history has put everything in its place.

The remains of the royal family were discovered and identified using modern methods. On July 17, 1998, they were buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. In 2000, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized Emperor Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, princesses Olga, Maria, Tatiana, Anastasia, and Tsarevich Alexei as martyrs.

Nowadays, there are also arranged marriages that occur among the political or economic elite. Such marriages are viewed more as a connection between different families (surnames, clans) than a personal relationship between a man and a woman. Although representatives of both families offer partners for future marriage, the decision remains with their children. Often, contractual relationships lead to good relationships and successful marriages over time.

At one time, the son of the President of Kyrgyzstan, Aidar Akayev, and the daughter of the President of Kazakhstan, Aliya Nazarbayeva, got married.

Another “dynastic marriage” of the century: not long ago, the son of the owner of Crocus International, Emin Agalarov, married Leyla Aliyeva, the daughter of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev and the granddaughter of former President Heydar Aliyev.

Emin Agalarov was among the most eligible bachelors. He is attractive, well educated (he studied in the USA and Switzerland), and most importantly, he is the heir to a multimillion-dollar fortune.

Back in 2004, Forbes magazine included his father Aras Agalarov among the hundred richest Russians, placing him in 66th place with a capital of $360 million. Agalarov Sr. himself boasted that he plans to increase capital to $1 billion. However, Emin Agalarov is beautiful not only because of his father’s condition. His assets include his own acumen and efficiency. Now the twenty-five-year-old representative of the Agalarov dynasty is the commercial director of Crocus International. In addition, he is interesting as a person, musical, has a good voice, because he studied vocals with Muslim Magomayev himself.

Leyla Aliyeva is a worthy match for such a groom. She is a beautiful young girl, brought up in a Swiss school, pretty and smart. She is engaged in social activities, is the president of the foundation of her grandfather Heydar Aliyev, promotes recreation and resorts on the Caspian Sea, in addition, she is the publisher and editor-in-chief of the glossy magazine “Baku”.

Each marriage is the intersection of two family trees, with huge “crowns of ancestors.” And the ancestors are not indifferent: whether the branches of the family wither or bloom with many beautiful fruits. .

Dynastic marriages led to the fact that marital ties began to be concluded between cousins. Such marriages are called cousin marriages. In the next chapter we will move on to examine such marriages.

Dynastic marriages of the ruling dynasty

Dynastic marriages were not uncommon in Kievan Rus. Vladimir also sent part of his wax to the rescue of the Byzantine Empire from the rebels, demanding in return the hand of his younger sister Vasily and Constantine (emperors of Byzantium). The Kiev prince understood perfectly well that he had a rare opportunity to become related to the rulers of the Byzantine Empire.

But nevertheless, dynastic marriages received the greatest development during the reign of Yaroslav the Wise.

This is what we read in the Chronicle of Adam of Bremen, already well known to us, in a note (scholia) to the story of the Norwegian king Harald the Severe Ruler (1046-1066)19

“Returning from Greece, Harald married the daughter of King Yaroslav of Rus'; the other went to the Hungarian king Andrew, from whom Solomon was born, the third was taken by the French king Henry, she gave birth to Philip (King Philip, 1060-1108)

Each of these three marriages had, of course, (or even - primarily) a political side. We will try to restore it, as far as Western European sources allow. The marriage of Elizabeth Yaroslavna, which apparently took place ca. 1042-1044, when Harald was in Rus' shortly before his invitation to the Norwegian throne, is covered mainly by monuments of Scandinavian origin. We will be more interested in the fate of her sisters.

The daughter of the Russian prince Yaroslav the Wise, Elizabeth, is known only from the Icelandic sagas, where she bears the name “Ellisif” or “Elisabeth”. In a number of royal sagas, records from the beginning of the 13th century. (in “Rotten Skin”, “Beautiful Skin”, “The Earthly Circle”, “The Saga of the Knüttlings”), as well as (without mentioning the name of the bride) in the “Acts of the Bishops of the Hamburg Church” by Adam of Bremen (c. 1070) contains information about the marriage of Elizabeth and Harald the Cruel Ruler (Norwegian king from 1046 to 1066). A comparison of the news of the sagas with the data of the Icelandic annals leads to the conclusion that the marriage was concluded in the winter of 1043/44. The story of the marriage of Harald and Elizabeth, as described by the sagas, is very romantic20.

“On Wednesday, the fourth calendar of August” (i.e., July 29), 1030, the famous Norwegian king Olav Haraldsson (1014-1028) died in the battle of Stiklastadir against the army of Lendrmanns and Bonds. His maternal half-brother, Harald Sigurdarson, then fifteen years old, participated in the battle, was wounded, fled from the battle, went into hiding, was treated, crossed the mountains to Sweden, and set off the following spring, according to the Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson in the set of royal sagas “The Earthly Circle” (c. 1230), “to the east to Gardariki to King Yaritsleiv,” that is, to Russia to Prince Yaroslav the Wise.

Snorri goes on to say that “King Jaritsleif received Harald and his men well. Then Harald became chief of the king's people who guarded the country... Harald remained in Gardariki for several winters and traveled throughout Austrweg. Then he set out on a journey to Grickland, and he had a large army. He was then on his way to Miklagard”21

The reason for Harald’s departure is explained in “Rotten Skin” (1217-1222). It says that “Harald traveled throughout Austrweg and accomplished many feats, and for this the king highly valued him. King Yaritsleif and Princess Ingigerd had a daughter named Elisabeth, the Normans call her Ellisiv. Harald started a conversation with the king to see if he would like to give him the girl as a wife, saying that he was known by his relatives and ancestors, and also partly by his behavior.” Yaroslav said that he could not give his daughter to a foreigner who “has no state to rule” and who is not rich enough to buy the bride, but he did not reject his proposal and promised to “preserve his honor until a convenient time.” It was after this conversation that Harald set off, reached Constantinople and spent about ten years there (c. 1034-1043) in the service of the Byzantine emperor22.

Returning to Russia, being the owner of such enormous wealth, “which no one in the Northern lands had ever seen in the possession of one person,” says Snorri Sturluson, “Harald laid down the Vys of joy, and there were sixteen of them in total, and everyone had the same end.”23 The same the same stanza as in “The Earthly Circle” is quoted in another set of royal sagas, “Beautiful Skin” (c. 1220). In "Rotten Skin" and "Hulda" six stanzas of Harald are given, dedicated to "Elisabeth, daughter of King Jaritsleif, whose hand he asked." The stanzas are introduced with the words: “... and in total there were sixteen of them, and they all had one end; here, however, few of them are recorded.”

In the spring, the sagas report with reference to the skald Valgard from Vella (“You launched [the water] a ship with a beautiful cargo; honor fell to you; you took, indeed, gold from the east from Gard, Harald”), Harald set out from Holmgard through Aldeigjuborg to Sweden. In the Icelandic annals we read: “1044. Harald [Sigurdarson] has arrived in Sweden." On this basis we can conclude that the marriage of Harald and Elizabeth was concluded in the winter of 1043/44.24

Not a single source, talking about Harald’s departure from Rus', says that Elizabeth was with him on this journey. True, this conclusion can be reached based on the absence in the sagas of indications that their two daughters (Maria and Ingigerd, unknown, like Elizabeth, to Russian sources, know “Rotten Skin”, “Beautiful Skin”, “Earthly Circle” and "Hulda") were twins - otherwise Harald and Elizabeth, who, according to the sagas, spent one spring together between the wedding and Harald's sailing, could have only had one daughter.

This is confirmed by the subsequent news of the sagas that after many years, leaving Norway, Harald took Elizabeth, Mary and Ingigerd with him. According to the “Earthly Circle” and “Hulda,” Harald left Elizabeth and his daughters on the Orkney Islands, and he himself sailed to England25.

The marriage of Harald Sigurdarson and Elizabeth Yaroslavna strengthened Russian-Norwegian ties, which were friendly during the time of Olav Haraldsson - at least since 1022, i.e., from the death of Olav Sjötkonung, Yaroslav's father-in-law, and Onund-Jacob's coming to power in Sweden, who soon entered into an alliance with Olav Haraldsson against Cnut the Great - and during the time of Magnus the Good (1035-1047), elevated to the Norwegian throne not without the participation of Yaroslav the Wise.

The matchmaking and wedding of Anna Yaroslavna took place in 1050, when she was 18 years old.

Already at the beginning of her royal journey, Anna Yaroslavna accomplished a civic feat: she showed persistence and, refusing to swear in the Latin Bible, took an oath in the Slavic Gospel, which she brought with her. Under the influence of circumstances, Anna would then convert to Catholicism. Arriving in Paris, Anna Yaroslavna did not consider it a beautiful city. Although by that time Paris had transformed from the modest residence of the Carolingian kings into the main city of the country and received the status of the capital. In letters to her father, Anna Yaroslavna wrote that Paris was gloomy and ugly, she complained that she ended up in a village where there were no palaces and cathedrals, which Kyiv was rich in.

At the beginning of the 11th century in France, the Carolingian dynasty was replaced by the Capetian dynasty, named after the first king of the dynasty, Hugo Capet. Three decades later, Anna Yaroslavna's future husband Henry I, son of King Robert II the Pious (996-1031), became the king of this dynasty. Anna Yaroslavna's father-in-law was a rude and sensual man, however, the church forgave him everything for his piety and religious zeal. He was considered a learned theologian.

Having been widowed after his first marriage, Henry I decided to marry a Russian princess. The main motive for this choice is the desire to have a strong, healthy heir. And the second motive: his ancestors from the house of Capet were related by blood to all neighboring monarchs, and the church forbade marriages between relatives. So fate destined Anna Yaroslavna to continue the royal power of the Capetians.

Anna's life in France coincided with the economic boom in the country. During the reign of Henry I, old cities were revived - Bordeaux, Toulouse, Lyon, Marseille, Rouen. The process of separating crafts from agriculture is moving faster. Cities begin to free themselves from the power of lords, that is, from feudal dependence. This entailed the development of commodity-money relations: taxes from cities bring income to the state, which contributes to the further strengthening of statehood.

The most important concern of Anna Yaroslavna's husband was the further reunification of the Frankish lands. Henry I, like his father Robert, led expansion to the east. The Capetian foreign policy was characterized by the expansion of international relations. France exchanged embassies with many countries, including the Old Russian state, England, and the Byzantine Empire.

Anna Yaroslavna was widowed at the age of 28. Henry I died on August 4, 1060 at the castle of Vitry-aux-Lages, near Orleans, in the midst of preparations for war with the English king William the Conqueror. But the coronation of Anna Yaroslavna's son, Philip I, as co-ruler of Henry I took place during his father's lifetime, in 1059. Henry died when the young King Philip was eight years old. Philip I reigned for almost half a century, 48 years (1060-1108). He was a smart but lazy man.

In his will, King Henry appointed Anna Yaroslavna as his son's guardian. However, Anna, the mother of the young king, remained queen and became regent, but, according to the custom of that time, she did not receive guardianship: only a man could be a guardian, and that was Henry I’s brother-in-law, Count Baudouin of Flanders.

According to the then-existing tradition, Dowager Queen Anne (she was about 30 years old) was married off. Count Raoul de Valois took the widow as his wife. He was known as one of the most rebellious vassals (the dangerous Valois family had previously tried to overthrow Hugh Capet, and then Henry I), but, nevertheless, he always remained close to the king. Count Raoul de Valois was a lord of many possessions, and he had no fewer warriors than the king. Anna Yaroslavna lived in the fortified castle of her husband Montdidier.

Anna Yaroslavna was widowed for the second time in 1074. Not wanting to depend on Raoul's sons, she left the Montdidier castle and returned to Paris to her son the king. The son surrounded his aging mother with attention - Anna Yaroslavna was already over 40 years old. Her youngest son, Hugo, married a wealthy heiress, daughter of the Count of Vermandois. His marriage helped him legitimize the seizure of the count's lands.

Little is known from historical literature about the last years of Anna Yaroslavna’s life, so all available information is interesting. Anna eagerly awaited news from home. The news came different - sometimes bad, sometimes good. Soon after her departure from Kyiv, her mother died. Four years after the death of his wife, at the age of 78, Anna’s father, Grand Duke Yaroslav, died. The illness broke Anna. She died in 1082 at the age of 50.

Data from Hungarian sources about the marriage of the Hungarian king Andrew (in Hungarian - Endre) I (1046-1060) to a Russian princess serve, in essence, as the first truly definite and reliable evidence of Russian-Hungarian political relations.

Shimon Kezai, and the arch of the 14th century. draw the political background of this union. King Istvan's nephews, brothers Andrei, Bela and Levente, were expelled by their uncle from the country: Bela (the future king Bela I) remained in Poland, marrying the sister of the Polish prince Casimir I, and Andrei and Levente went further “to Rus'. But since there they were not accepted by Prince Vladimir because of King Peter, after that they moved to the land of the Polovtsians from there “after some time,” as added in the 14th century code, they again “returned to Rus'.”26

Judging by this story, the appearance of Hungarian exiles in Volyn (where at that time one of the Yaroslavichs, either Izyaslav or Svyatoslav, was probably governor) falls already during the reign of King Peter in Hungary (1038-1041, 1044-1046). ), which was oriented towards Germany and enjoyed its support. And therefore, the refusal received by Andrei and Levente in Rus' is quite understandable in view of the fact that we know about the friendliness of Russian-German relations ca. 1040

But soon the situation changed dramatically. The policy of Yaroslav Vladimirovich, loyal to Peter, is replaced by the support of his rival - the rebellious anti-king Aba Sha-muel (Samuel) (1041-1044), also one of the nephews of the late Istvan I. The message of the German Regensburg Chronicle of Emperors "27, written by between 1136 and 1147 in Old High German by an anonymous Regensburg monk-poet.

His story, which is generally based on well-known sources, in the part concerning Shamuel, is completely original and contains unique information. According to the Chronicle of Emperors, defeated by Peter in 1044, with German help, Shamuel “quickly gathered, Taking his children and wife, He fled to Rus'.

Judging by other sources, the escape was unsuccessful, but the fact itself is important. No matter how one views this information, the further development of events is beyond doubt: after the defeat of Shamuel, Rus' also supported Peter’s other rival, Andrei. The Hungarian nobility “sent solemn envoys to Rus' to Andrei and Leventa” to hand them the throne, on which Andrei was installed in 1046, provoking repeated but unsuccessful campaigns of the German Emperor Henry III. Apparently, in 1046 or a little earlier, when Yaroslav’s political interest in the figure of Andrei became apparent, and the marriage took place.

The personality of Anastasia (while maintaining prudent skepticism, we will not completely rely on a rather late author) Yaroslavna is better imprinted in the Hungarian tradition; cf., for example, a passage from “The Acts of the Hungarians of Anonymous”, not without some lyricism: Andrei often spent time in the Komárom castle “for two reasons: firstly, it was convenient for royal hunting, and secondly, he loved to live in those places wife, because they were closer to [her] homeland - and she was the daughter of a Russian prince and was afraid that the German emperor would come to avenge the blood of [King] Peter.”

Leaving on the conscience of “Anonymous” his weakness in geography (Komarom was located on the Danube, near the mouth of the Vah River, i.e. noticeably closer to the German border than to the Russian), we note the play of fate: when by the end of Andrei’s reign the political scenery had already undergone even more one radical change and Andrei was overthrown by the brother of Bela I (1060-1063), Anastasia and her son Shalmon, married to the sister of the German king Henry IV (1056-1106), found refuge in Germany. And the entire period of Shalamon’s reign (1063-1074, died ca. 1087) he had to defend the throne in the fight against the sons of Bela - Geza and Laszlo, who were looking for support, including in Rus' (they were nephews of Gertrude, the wife of the Kiev prince Izyaslav Yaroslavich). Anastasia, according to legend, died her days in the German monastery of Admont, not far from the Hungarian-German border.

It is possible to understand Vsevolod’s political position by taking into account the marriage of his son Vladimir Monomakh, which was concluded precisely during the period we are studying. Vladimir Vsevolodovich married Gida, the daughter of the last Anglo-Saxon king Harald, who died in 1066. Information about this marriage has been used in science for a long time, but when trying to determine its political meaning, historians were forced to limit themselves to general phrases. It seems that here, too, new data on Svyatoslav’s foreign policy brings sufficient clarity.

The dating of the marriage of Vladimir Monomakh and Hyda (1074/75), widespread in science, is conditional and is based solely on the date of birth of the eldest of the Monomachis, Mstislav (February 1076). The Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus claims that this matrimonial union was concluded on the initiative of the Danish king Sven Estridsen, who was a cousin of Gida’s father and at whose court she stayed after she was forced to leave England. A possible motive for Sven's actions is sometimes seen in the fact that his second marriage was supposedly to the daughter of Yaroslav the Wise, Elizabeth, who was widowed in 1066 (her first husband, the Norwegian king Harald the Harsh, died in the Battle of Stanfordbridge against Harald, Gida's father).

But this misconception, coming from the old Scandinavian historiography, is based on an incorrect interpretation of the message of Adam of Bremen (70s of the 11th century)28, where we are actually talking about the marriage of the Swedish king Hakon, and not to Elizabeth Yaroslavna, but to “ mother of Olav the Younger,” that is, the Norwegian king Olav the Quiet, who was not the son, but the stepson of Elizabeth. Taking into account the role of Sven Estridsen in choosing a bride for Vsevolodov’s son, one cannot help but pay attention to the close allied relations between the Danish king and Henry IV in the 70s.

They meet in person at Bardowik, near Lüneburg, in 1071 and perhaps again in 1073; in the fall of 1073, Sven even took military action against the Saxons fighting with Henry. Commentators are probably right in doubting the validity of the opinion of Lampert of Hersfeld (who was inclined to see the anti-Saxon machinations of Henry IV in everything), as if already in 1071, during negotiations with Sven, there was talk of joint actions against the Saxons.

Therefore, it would hardly be too bold to assume that, in addition to matters related to the Hamburg Metropolitanate, the sudden conflict between Germany and Poland was also discussed. The simultaneity of the German-Chernigov and German-Danish negotiations suggests that the initiative shown by the Danish king during the marriage of Vladimir Monomakh and Gida could be connected with these negotiations. Based on the above, it seems to us that Vsevolodovich’s marriage to an English exiled princess should be considered as a manifestation of the coordinated international policy of Svyatoslav and Vsevolod in 1069-1072, aimed at isolating Boleslav II, the main ally of Izyaslav Yaroslavich.29

In this case, the marriage of Vladimir Monomakh should have taken place between 1072 (the German-Danish meeting in Bardovik took place in the summer of the previous year) and 1074. There is no reason to date Vsevolod’s accession to the German-Danish-Chernigov coalition against Poland to a later time, since at the turn of 1074-1075. The “Polish question” lost its relevance for the younger Yaroslavichs. It was by this time that their relations with Boleslav II were settled, which resulted not only in the scandalous expulsion of Izyaslav from Poland (in the words of the chronicler, “the Lyakhov took everything from him, showing him the way from himself”) at the end of 1074 and peace between Poland and Russia after Easter 1075, but also a joint action against the Czech Republic with the participation of Oleg Svyatoslavich and Vladimir Monomakh in the fall - winter of 1075/76. thirty

All of the above helps to better understand the political steps that Izyaslav took in Lampert; he arrived to Henry IV in Mainz at the very beginning of 1075, accompanied by the Thuringian margrave Dedi, at whose court he was subsequently found. Dedi received the Thuringian Mark along with the hand of Adela of Brabant, the widow of the previous Thuringian margrave Otto of Orlamund, from whom Adela had two daughters - Oda and Cunegonde. And so, from the Saxon annalist we find an interesting message that Cunegonde, it turns out, married the “King of Rus'” (“regi Ruzorum”), and Oda married Ecbert the Younger, the son of Ecbert the Elder of Brunswick. After some hesitation, the researchers found the correct solution, identifying the husband of Cunegonde of Orlamund with Yaropolk, the son of Izyaslav Yaroslavich.

31We will try to establish the time when this marriage took place. Margrave Dedi, after negotiations between Henry IV and the leaders of the rebel Saxons in Gerstungen on October 20, 1073, left the camp of the Saxon opposition and until his death in the fall of 1075 remained loyal to the king. This means that getting closer to Dedi hardly made sense for Izyaslav during his stay in Poland in 1074, just as Dedi had no reason to seek kinship with the exiled prince. After Izyaslav moved to Germany at the end of 1074, his son Yaropolk was found in Rome in the spring of 1075, where he was negotiating with Pope Gregory VII, the purpose of which was to induce the pope to put pressure on Boleslav of Poland. The letters of Gregory VII to Izyaslav and Boleslav II, which were the result of negotiations between Yaropolk and the pope, are dated April 17 and 20; therefore, the negotiations themselves probably took place in March - April, after the end of the Lenten Synod on February 24-28. Therefore, it is unlikely that Izyaslav had enough time to marry his son before his departure to Italy. But after Yaropolk returned to the court of Dedi (apparently in May 1075), the situation became fundamentally different. And the point is not only that Izyaslav enlisted the support of the Roman high priest, receiving from his hands the Kiev table as a “gift of St. Peter” (“dono sancti Petri”); more important than the change in the position of Henry IV.

The change in Svyatoslav's political course in 1074 is understandable: the Saxon uprising in the summer of 1073, which diverted all the forces of the German king, disrupted plans for joint actions against Poland. Svyatoslav’s new political course became obvious to Henry, presumably, after the return of Burchard’s embassy in July 1075. Moreover, it is very plausible to assume that the military actions in Thuringia undertaken by Henry in September 1075 together with the Czech prince and at the head of the Czech The troops were suddenly interrupted, ending with a hasty retreat to the Czech Republic in connection with the Russian-Polish campaign against Bratislava, which began at that time.

It is easy to imagine that all this could cause a sharp turn in Henry IV’s attitude towards Izyaslav and result in the marriage of Yaropolk Izyaslavich with the daughter of the Thuringian margrave. What explained the choice of a bride for the Russian prince? Important was, of course, the position of Cunegonde's stepfather, Margrave Dedi. But, knowing the origin of Oda, Svyatoslav’s wife, it is impossible not to note that Izyaslav married his son to the sister of the wife of the Meissen margrave Ecbert the Younger, Oda’s cousin. It must also be taken into account that Udon II, adopted by Ida of Elsdorf and thus Oda's brother and uncle of Ecbert the Younger, owned the Saxon North March at this time (died 1082). We see how “Russian marriages” of the first half of the 70s. cover all Saxon brands, i.e. all territories bordering Poland. It is quite obvious that Izyaslav sought to undermine the position of Svyatoslav, whose entire Polish policy in 1070-1074. was built on an alliance with the East Saxon nobility. Izyaslav’s family ties through his daughter-in-law Cunegonde seem to “overlap” the earlier connections of his younger brother.

This kind of Russian-Saxon contacts can be considered traditional for Rus'. Indeed, for half a century, under Yaroslav the Wise and the Yaroslavichs, the strained relations of the Russian princes with Poland always entailed alliances with the East Saxon margraves. Back in the 30s. XI century The joint struggle of Yaroslav the Wise and the German Emperor Conrad II against the Polish King Meshko II was sealed by the marriage of the Russian princess with the Margrave of the same Saxon northern mark, Bernhard. Likewise, in the mid-80s, during the struggle of Vsevolod Yaroslavich with Yaropolk Izyaslavich of Volyn, just like his father, who relied on Polish support, Vsevolod married his daughter Eupraxia to the Margrave of the Saxon North Mark, Henry the Long, son of Udon II. Such remarkable continuity in ancient Russian foreign policy deserves special study.32

The emerging picture of the international policy of the Yaroslavichs in the 70s. XI century will be incomplete if you do not pay due attention to one more of its flanks - the Hungarian one. In Hungary at this time, a struggle unfolded between King Shalamon (1064-1074), supported by Germany, and his

Cousins - Geza, Laszlo and Lambert, traditionally associated with Poland (their father, Bela I, was in exile in Poland for a long time). Data on Russian-Hungarian relations at this time are extremely scarce. In essence, all that is known is that, following Lambert, who sought help from Boleslav of Poland in 1069, Laszlo went to Rus' in 1072 for the same purpose, but his mission was not successful, as is commonly believed, due to internal turmoil in Russia114 . The question of why

In Rus', the sons of Bela I hoped to receive help, and to whom exactly Laszlo went for it was not determined due to a lack of sources. In our opinion, something can be clarified here if we take into account the information now at our disposal about the foreign policy confrontation between Izyaslav of Kiev and Svyatoslav of Chernigov in the early 70s.

Oda, the wife of Svyatoslav, being the daughter of the early deceased Lutpold Babenberg, turns out to be the niece of the then Margrave of the Bavarian East Mark Ernst. It is extremely noteworthy that Izyaslav’s calculation could also be connected with the figure of Ernst when he married his son to the stepdaughter of Margrave Dedi: the fact is that Ernst was married to Dedi’s daughter from a previous marriage. If we take into account that the Bavarian East Mark on the German-Hungarian border played the same role as the East Saxon marks on the German-Polish border, then the presence of the “Hungarian question” in the negotiations of Henry IV both with Svyatoslav around 1070 and with Izyaslav in the fall of 1075 it will become quite probable. In any case, it should be clear that there was no unified ancient Russian policy either in relation to Poland or in relation to Hungary at that time; international relations between Kyiv and the Chernigov-Pereyaslav coalition should be considered separately.

Then it is logical to assume that Laszlo, in search of help, went to Izyaslav, who was firmly connected with Poland, but encountered opposition from the younger Yaroslavichs, who, due to their alliance with Henry IV, were inclined to support Chalamon. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Volyn, bordering Hungary, was at that time probably in the hands of Vsevolod.

And in the Hungarian question, the year 1074 was supposed to bring with it a radical reorientation of Svyatoslav’s policy. What makes one think so is not only the crisis of his alliance with Henry IV, which resulted in direct military cooperation with Boleslav of Poland, but also the simultaneous rapprochement of Geza I and the younger Yaroslavichs with Byzantium. Geza I, who seized the Hungarian throne in 1074, married a Greek woman (possibly the niece of the future Emperor Nikephoros III Votaniates - then the son-in-law of Emperor Michael VII Duca) and was even crowned with a crown sent from Byzantium. At the same time (according to V. G. Vasilievsky, in 1073-1074) Michael VII entered into negotiations with Svyatoslav and Vsevolod Yaroslavich, offering to marry the daughter of one of them (probably Vsevolod) to his porphyry brother Constantine. Obviously, as a result of some agreement reached at that time, Constantinople also received Russian military assistance in suppressing the rebellion in Korsun.

Conclusion

The marriages of representatives of the Kyiv dynasty indicated that Rus' occupied a prominent place in the system of European states, and its ties with the Latin West were the closest. Yaroslav the Wise betrothed the daughter of the Polish king Mieszko II to his son Izyaslav, and the daughter of the German king Leopold von Stade to his son Svyatoslav. The youngest of the three Yaroslavichs, Vsevolod, married a relative of Emperor Constantine Monomakh. Among Yaroslav's daughters, the eldest Agmunda-Anastasia became the Hungarian queen, Elizabeth - the Norwegian and then the Danish queen, Anna - the French queen. Anna's marriage was unhappy and she fled from her husband to Count Raoul II of Valois. Royal power in France was in decline, and King Henry I could not return his wife.

The crowning achievement of the matrimonial successes of the Kyiv house was the marriage of Euphrosyne, daughter of Vsevolod Yaroslavich, with the German Emperor Henry V. The marriage was short-lived. After a noisy divorce process, Euphrosyne returned to Kyiv. Euphrosyne's brother Vladimir Monomakh married the exiled princess Gita. Gita's father Harald II was the last of the Anglo-Saxon royal dynasty. The Norman Duke William the Conqueror defeated the Anglo-Saxons. Harald died, and his daughter Gita took refuge in Denmark, from where she was brought to Kyiv.

Organic inclusion of the Rurikovichs into the system of dynastic ties of the ruling houses of the Christian states of Europe in the 11th - early 12th centuries. indicates that they considered Rus' as a socially and politically equal partner, and that it itself remained in a single cultural and political European space.

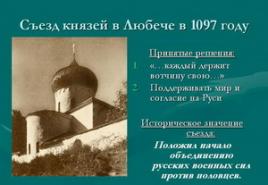

Peace and tranquility in the state can be ensured in different ways. You can fight, conclude treaties, find allies. But there is the simplest and surest way to achieve this goal, the most win-win tactic - dynastic marriage. Yaroslav Vladimirovich, Grand Duke of Kiev, understood this like no one else.

All of Yaroslav's sons were married to ruling princesses - Byzantium, Poland, and Germany.

The eldest son, Vladimir, was a prince in Novgorod and was married to a northern princess, whom some chroniclers considered the daughter of the English king Harald. But N.M. Karamzin in “History of the Russian State” writes: “Referring to the Norwegian chroniclers, Torfey calls Vladimir, Yaroslav’s eldest son, the husband of Gida, daughter of the English king Harald, defeated by William the Conqueror. Saxo Grammaticus, the oldest Danish historian, also narrates that the children of the unfortunate Harald, killed in the Battle of Hastings, sought refuge at the court of Svenon II, king of the Danish, and that Svenon then gave his daughter Haraldov to a Russian prince, named Vladimir; but this prince could not be Yaroslavich. Harald was killed in 1066, and Vladimir, the son of Yaroslav, died in 1052, having built the Church of St. Sophia in Novgorod, which has not yet been destroyed by time and where his body is buried.”

The wife of the next son of Yaroslav the Wise, Izyaslav (baptized Dmitry), was the Polish princess Gertrude, in Orthodoxy - Elizabeth. Gertrude married Izyaslav in 1043, in 1050 she gave birth to a son, Yaropolk, and in 1073 she was forced to flee with them to her homeland, since her husband’s brothers Svyatoslav and Vsevolod expelled him from his great reign. From Poland the princely family went to Saxony, where Elizabeth returned to the “Latin faith.” On the advice of his mother, Yaropolk turned to Pope Gregory VII with a request for support. In 1077, Izyaslav Yaroslavich captured Kiev and reigned there. Grand Duchess Elizabeth and her son returned to Rus' and were baptized into Orthodoxy. Elizabeth spent the next 20 years in her son’s inheritance – Vladimir-Volyn, where she distinguished herself in matters of public administration, having an attribute of state power – personal seals (kept in the Department of Archeology of the Institute of Social Sciences of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Lvov). Elizabeth owned the famous Trier Psalter (“Gertrude Code”) with miniatures made to her order and depicting her and her son Yaropolk. The Psalter was given by Elizabeth to her daughter Sbyslava, who was married to a Polish prince in 1102, and was subsequently passed down through the female line of the family .

Svyatoslav (baptized Nikolai) Yaroslavich was the prince of Chernigov, and at one time also of Kyiv. His first marriage was to a certain Kyllikia (Cecilia?), whose origin is unknown. For his second marriage, the prince married Oda, a German countess who was the grandniece of Pope Leo IX and the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III. Oda was a descendant of many noble European dynasties and historical figures, including Charlemagne, King Alfred of England and Henry the Fowler.

The fourth, most beloved son of Grand Duke Yaroslav the Wise, Vsevolod (baptized Andrei) was the prince of Pereyaslavl, and then of Kyiv. His first marriage was to Anna (Maria?, Irina?), daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomakh. The wedding was celebrated in 1046 in honor and to seal the peace treaty between Russia and Byzantium with family ties. In 1053, the young couple had a son, who was named after his grandfather Vladimir, and in Christianity they gave him, like his grandfather, the name Vasily. This was the future Grand Duke of Kiev Vladimir Monomakh. Anna died in 1067. The second wife of Vsevolod Yaroslavich was the Polovtsian princess Anna.

It is interesting to note that the Russian princes willingly married their sons to Polovtsian women, but did not marry off their daughters to Polovtsian khans. The princesses always married Christians and never “filthy” ones. This is explained by a reason that was obvious at that time: if you married a Polovtsian woman, then after the wedding she converted to the Orthodox faith. And faith did not suffer from this. If a girl of a princely family went to the Steppe, then she was lost to the Christian faith, which could not be allowed.

Finally, the younger sons of Yaroslav: Vyacheslav-Mercury, Prince of Smolensk, and Igor-George (or Konstantin?), Prince of Vladimir-Volyn and Smolensk, married German princesses: Vyacheslav Yarovlavich - to Oda Leopoldovna, Countess of Stadenskaya, Igor Yaroslavich - to Cunegonde, Countess of Orlaminda, daughter of the Saxon Margrave Otten.

Yaroslav the Wise became related to almost all the august European houses, setting a kind of world record for the number of family dynastic ties. All these marriages show how Rus''s international authority has grown. Subsequently, Yaroslav's example was repeated more than once by his eminent descendants. The wives of the Kyiv princes were beauties from the enemy camp - Polovtsian women, as well as well-born Greeks, Czechs, and Polish princesses. Vladimir II Monomakh, who was the grandson of Yaroslav the Wise and the Byzantine ruler Constantine Monomakh, was himself married to Gita, the daughter of the English king Harold; Vladimirov's sister Eupraxia was married by the German Emperor Henry IV.

He received it not during his lifetime, but only in the 60s of the 19th century. During his lifetime he was called Lame. Research shows that his leg was severed, which means he was limping. At that time, such a deficiency was considered a sign of wisdom, intelligence, and providence, so the word “lame” as a nickname could be considered as close in meaning to the word “wise.” So they began to call Yaroslav - the Wise. The actions of this prince speak eloquently for themselves. The flourishing of the Old Russian state under Yaroslav the Wise is confirmation of these words.

Unification of Rus'

Yaroslav did not immediately become the ruler of Kyiv; he had to fight with his brothers for the Kiev throne for quite a long time. After 1019, Yaroslav united almost all the lands of the ancient Russian state under his rule, thereby helping to overcome feudal fragmentation within the country. In many areas, his sons became governors. Thus began the flourishing of the Old Russian state under Yaroslav the Wise.

Russian truth

An important step forward for Yaroslav’s domestic policy was the drawing up of a general set of laws, which was called “Russian Truth”. This is a document that defined the rules of inheritance, criminal, procedural and commercial legislation that are common to all. The flourishing of the Old Russian state under Yaroslav the Wise was impossible without this document.

These laws contributed to strengthening relations within the state, which generally contributed to overcoming feudal fragmentation. After all, now each city did not live by its own rules - the law was common to everyone, and this, of course, contributed to the development of trade and created the opportunity to stabilize relations within the state as much as possible.

The laws of “Russian Pravda” reflected the social stratification of society. For example, fines for killing a serf or a serf were several times less than payments for killing a free person. Fines filled the state treasury.

The rise of Kyiv

The very appearance of “Russian Truth” was a giant step forward towards overcoming feudal fragmentation and unifying different parts of the country. The Old Russian state flourished actively under Yaroslav the Wise. History reports that Kyiv has truly become the center of the country. The development of crafts contributed to trade relations. Merchants flocked to the city offering their goods. Kyiv grew rich, and its fame spread throughout many cities and countries.

Yaroslav the Wise

The flourishing of the Old Russian state under Yaroslav the Wise was also reflected in foreign policy. Events during this period were aimed at strengthening borders and developing relations with neighboring countries, primarily with Western Europe. This influenced the increase in the authority of the state. Relations with other countries have reached a higher level.

Despite the fact that the flourishing of the Old Russian state under Yaroslav the Wise was gaining momentum, historical events were not only positive. Rus' continued to suffer from raids by nomads. But soon this trouble was resolved. In 1036, the troops of Yaroslav the Wise defeated the Pechenegs, who after that stopped attacking Rus' for a long time. By order of the prince, fortress cities were built on the southern border to defend the borders.