Equipment and weapons of the Spanish army of the 17th century. Tertia dies but doesn't give up

V. INFANTRY OF THE XVI AND XVII CENTURIES

The longbow had recently disappeared from the European continent, with the exception of Turkey; The crossbow was last used by the Gascons in France in the first quarter of the 16th century. It was everywhere replaced by the matchlock musket, and this musket, in varying degrees of perfection, or rather imperfection, henceforth became the second type of infantry weapon. Matchlock muskets of the 17th century - clumsy mechanisms of imperfect design - were of too large a caliber to provide, in addition to range, at least some accuracy in shooting and the power to pierce a pikeman's breastplate. The generally accepted type of firearm around 1530 was a heavy musket, which was fired from a fork, since without such a support the shooter could not take aim. Musketeers carried a sword, but did not have defensive weapons and were used either for skirmishing in a loose formation, or in a special open formation to hold defensive positions or to prepare an attack by pikemen on such positions. They soon became very numerous in proportion to the pikemen; in the battles of Francis I in Italy they were still significantly inferior to the latter in numbers, but 30 years later they were at least equal to them. This increase in the number of musketeers necessitated the discovery of some tactical ways of correctly placing them in the general battle order. This was done in a tactical system called the Hungarian order of battle, which was created by the imperial forces during their wars with the Turks in Hungary. The musketeers, unable to defend themselves in hand-to-hand combat, were always positioned in such a way as to be able to take cover behind the pikemen. Thus, they were sometimes located on both flanks, sometimes on the four flank corners; very often the entire square or column of pikemen was surrounded by a line of musketeers, the latter being protected by the pikes of the warriors standing behind them. In the end, the principle of placing musketeers on the flanks of pikemen, applied in the new tactical system that was introduced by the Dutch in their War of Independence, prevailed. A distinctive feature of this system was the further division of three large phalanxes into which each army was divided, according to both Swiss and Hungarian tactics. Each of these phalanxes was built in three lines; the middle of them, in turn, was divided into right and left wings, separated from one another by a distance at least equal to the width of the front of the first line. The whole army was organized into semi-regiments, which we will call battalions; in each battalion, the pikemen were located in the center, and the musketeers on the flanks. The vanguard of the army, consisting of three regiments, was usually formed as follows: two half-regiments in a continuous front in the first line; behind each of its flanks is another half-regiment; further, in the rear, parallel to the first line, the remaining two half-regiments formed a continuous front. The main forces and the rearguard were placed either on the flank or behind the vanguard, but were usually formed in the same way. Here we have, to a certain extent, a return to the old Roman system, with its three lines and separate small units.

The Imperials, and with them the Spaniards, found it necessary to divide their large armies not into the above three groups, but into a larger number; but their battalions or tactical units were much larger than the Dutch, fought not in line formation, but in column or square, and had no permanent form for battle formation until, in the Dutch War of Independence, the Spaniards adopted for their troops the formation known called the Spanish Brigade. Four of these large battalions, each often consisting of several regiments, formed in a square, surrounded by one or two ranks of musketeers and having flanking groups of musketeers at their corners, were located at regular intervals on the four corners of the square, with one of the corners facing away enemy. If the army was too large to be combined into one brigade, two brigades could be formed, and thus three lines were obtained, the first having 2 battalions, the second 4 (sometimes only 3) and the third 2. Here, as and in the Dutch system we find an attempt to return to the old Roman system of three lines.

During the 16th century another significant change took place; the heavy knightly cavalry was disbanded and replaced by mercenary cavalry, armed, like our modern cuirassiers, with cuirass, helmet, broadsword and pistols. This cavalry, which was significantly superior in mobility to its predecessor, therefore became more formidable for the infantry; but still, the pikemen of that time were never afraid of her. Thanks to this change, cavalry became a uniform branch of the army and occupied a relatively much larger place in the army, especially during the period of the Thirty Years' War, which we must now consider. At this time, the military mercenary system was common in Europe; a category of people was formed who lived by war and for the sake of war; and although tactics may have benefited from this, the quality of the manpower - the material from which armies are formed and which determines their morale (moral state, moral character. Ed.) , - of course, it suffered from this. Central Europe was overrun by all kinds of condottieri, for whom religious and political strife served as a pretext to plunder and devastate entire countries. The individual qualities of the soldier were subject to degradation, which continued on an increasing scale until the French Revolution put an end to this system of military mercenaryism. The Imperials used the Spanish brigade system in their battles, placing 4 or more brigades in lines and thus forming three lines. The Swedes under Gustav Adolf were built into Swedish brigades, each consisting of 3 battalions, one in front and two slightly behind, and each battalion was deployed in a line and had pikemen in the center and musketeers on the flanks. Both types of infantry were positioned in such a way (they were represented in equal numbers) that, forming a continuous line, each of them could cover the other. Let us suppose that the order was given to form an unbroken line of musketeers; then both wings of the musketeers of the central or forward battalion would cover their pikemen by standing in front of them, while the musketeers of the other two battalions would advance each on their respective flank and form a line with the first. If a cavalry attack was expected, all the musketeers took cover behind the pikemen, while both flanks of the latter moved forward and formed in line with the center and thus formed a continuous line of pikemen. The battle formation was formed from two lines of such brigades, which formed the center of the army, while numerous cavalry were located on both flanks, interspersed with small detachments of musketeers. It is characteristic of this Swedish system that the pikemen, who in the 16th century were a branch of troops possessing great offensive power, have now lost all power of attack. They became merely a means of defense, and their purpose was to protect the musketeers from cavalry attacks; this last branch of the army again had to bear the brunt of the attack. Thus, the infantry lost and the cavalry regained its position. Following this, Gustav Adolf removed shooting from cavalry practice, which by that time had become the latter’s favorite method of combat; he ordered his cavalry to always attack at full gallop and with a broadsword in hand; and from this time, until the resumption of battles on rough ground, any cavalry that adhered to this tactic could boast of great success in competition with infantry. For the mercenary infantry of the 17th and 18th centuries there could be no more severe sentence than this, and yet in terms of the performance of all combat missions they were the most disciplined infantry of all time.

The general result of the Thirty Years' War for the tactics of European armies was that both the Swedish and Spanish brigades disappeared, and the armies were now deployed in two lines, with the cavalry forming the flanks and the infantry the center. Artillery was placed in front of the front of other types of troops or in the intervals formed by them. Sometimes a reserve was left, consisting of cavalry or cavalry and infantry. The infantry deployed in a line 6 ranks deep; muskets were so light that it was possible to do without a fork; cartridges and bandoleers were introduced in all countries. The combination of musketeers and pikemen in the same infantry battalions led to the most complex tactical formations, and the basis for all this was the need to form so-called defensive battalions, or, as we would call them, squares, to fight cavalry. Even when forming a simple square, it was not an easy matter to stretch out the six ranks of pikemen in the center so that they could surround the musketeers on all sides, who, of course, were defenseless against the cavalry; but what was it like to form a battalion in a similar way into a cross, an octagon, or some other bizarre shape! Thus it turned out that the system of military training during this period was more complex than ever, and no one except a soldier who had served all his life had the slightest chance of even approximately mastering it. At the same time, it is obvious that all attempts to form a battle formation in full view of the enemy, capable of repelling a cavalry attack, were completely in vain; any effective cavalry would be in the center of such a battalion before a fourth of all these reorganizations had been completed.

During the second half of the 17th century, the number of pikemen decreased significantly compared to the musketeers, since from the moment when the pikemen lost all their offensive power, the musketeers became a truly active part of the infantry. Moreover, it was found that the Turkish cavalry, the most formidable cavalry of the time, very often broke through the square of pikemen, while its charges were just as often repulsed by the well-aimed fire of the line of musketeers. As a result, the Imperials completely abolished the pikes in their Hungarian army and sometimes began to replace them with chevaux de frise (slingshots. Ed.), the assembly of which was carried out on the battlefield, and the musketeers wore the points from them as part of their regular equipment. In other countries it also happened that armies were sent into battle without a single pikeman: the musketeers relied on the effect of their fire and the support of their cavalry when they were threatened by a cavalry charge. But still, for the final abolition of the pike, two inventions were required: the bayonet, invented in France around 1640 and improved in 1699 so much that it became a convenient weapon used to this day, and the flintlock, invented around 1650. The bayonet, although, of course, could not completely replace the pike, gave the musketeer the opportunity to provide himself with a certain measure of protection, which previously, it was assumed, he usually received from the pikemen; The flintlock, having simplified the loading process, made it possible, through frequent shooting, not only to compensate for the shortcomings of the bayonet, but also to achieve significantly greater results.

From the book Superman Speaks Russian author Kalashnikov MaximGolem’s “hump-nosed infantry” The aliens, it would seem, should be inferior to the Russians in everything. Their educational level is low. Counting money, trading and delivering goods to “points” - is there great wisdom? They did not become famous by famous designers, scientists or

From the book Man: Thinkers of the past and present about his life, death and immortality. The ancient world - the era of Enlightenment. author Gurevich Pavel SemenovichRUSSIAN PHILOSOPHICAL THOUGHT OF THE 11th–17th CENTURIES In the Russian Middle Ages, the anthropological direction of philosophical thought was one of the main ones. The originality of Russian philosophical ideas about man, his calling and purpose in the world was determined by many circumstances.

From the book Volume 15 author Engels FriedrichF. ENGELS FRENCH LIGHT INFANTRY If ever our volunteers have to exchange bullets with the enemy, then this enemy will be - everyone knows it - French infantry; the best type - beau ideal [beautiful ideal. Ed.] - a French infantryman is a soldier

From the book Volume 14 author Engels FriedrichF. ENGELS INFANTRY Infantry are foot soldiers of the army. With the exception of nomadic tribes, among all peoples the bulk of the army, if not the entire army, has always consisted of foot soldiers. Thus, even in the first Asian armies - among the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians - the infantry was at least

From the book Utopia in Russia author Geller LeonidI. GREEK INFANTRY The creators of Greek tactics were the Dorians, and of the Dorians, the Spartans perfected the ancient Doric battle formation. Initially, all classes that made up Dorian society were required to undergo military service - not only

From the book Fundamentals of Philosophy author Babaev YuriII. ROMAN INFANTRY The Latin word legio was originally used to designate a body of men selected for military service, and was thus synonymous with army. Then, when the size of Roman territory and the strength of the enemies of the republic demanded larger

From the book Philosophy: Lecture Notes author Olshevskaya NatalyaIII. INFANTRY IN THE MIDDLE AGES The decline that the Roman infantry experienced continued in the Byzantine infantry. A kind of forced recruitment into the army still remained, but it did not provide anything other than the most unsuitable formations in the army. The best units of the army were auxiliary

From the book Philosophy. Cheat sheets author Malyshkina Maria ViktorovnaVI. INFANTRY OF THE 18TH CENTURY Together with the displacement of the pike from the equipment of the infantry, all types of defensive weapons disappeared, and from now on this branch of the army consisted of only one type of soldier, armed with a flintlock rifle with a bayonet. This change was completed in the early years of the Spanish War.

From the book Philosophy with a joke. About great philosophers and their teachings author Calero Pedro GonzalezVII. INFANTRY OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY AND 19TH CENTURY When the European coalition invaded revolutionary France, the French were in much the same position as the Americans had been shortly before, with the only difference being that they did not have the same advantages

From the book History of World Culture author Gorelov Anatoly AlekseevichChapter 2 Folk utopianism of the 17th–20th centuries

From the author's bookSpecifics of the development of idealistic traditions in the philosophical theories of the 17th–18th centuries The idealistic tradition in the philosophical theories of modern times also continues to be preserved and developed, providing its solution to the main philosophical and worldview problems that

From the author's bookPhilosophy of the 18th–19th centuries

From the author's book70. Postclassical philosophy of the 19th–20th centuries Postclassical philosophy of the 19th century is the stage of development of philosophical thought that immediately precedes modern philosophy. One of the main characteristics of this period of philosophy was irrationalism - the idea that

From the author's bookPhilosophy of the 15th–18th centuries With whom to share eternity? While occupying the position of secretary of the Second Chancellery in Florence, Niccolo Machiavelli became closely acquainted with Cesare Borgia. It must have been because of his friendship with this very controversial character, for whom Machiavelli never admired

From the author's book From the author's bookHistory of the Middle Ages In the history of the European Middle Ages, the early Middle Ages (V-XI centuries), mature (XII-XIII centuries) and later (XIV-XVI centuries) are distinguished. Thus, the Middle Ages also partially included the Renaissance, at least the Italian one, which dates back to the 14th–16th centuries. In other countries

At the end of the 15th century, the first centralized nation states emerged in Western Europe. Rich Italy was a patchwork quilt consisting of many small, militarily weak states at war with each other. France, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire (of the German nation) tried to take advantage of this situation. They tried to occupy parts of Italy and at the same time fought for dominance in Europe.

One of the oldest images of Spanish infantry during the Tunisian campaign of 1535. Although it is difficult to say from the clothes and weapons that these are Spaniards.

In 1493, the French king Charles VIII, as heir to Anjou, declared a claim to the Kingdom of Naples, which had been ruled by the Angevin dynasty since 1265. Although this kingdom was officially called the "Kingdom of the Two Sicilies", Sicily itself had been under the rule of the Spanish kingdom of Aragon since 1282. Charles VIII, preparing for conquest, concluded treaties with England, Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. In 1493, when the French king entered into an alliance with Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg, news spread throughout Europe that the navigator Columbus had discovered a sea route to India (in fact, it was a new, American continent, which he did not yet know about) and declared these lands his possession. Spanish king. This prompted Karl to act quickly. With a small army, the basis of which was mobile artillery, new at that time, and 10,000 Swiss mercenaries, he crossed the Alpine pass of Mont Genèvre and occupied Naples with virtually no resistance.

Detail of the Battle of Pavia (1525), when the army of Charles V inflicted a decisive defeat on the French. Hand-to-hand combat between French (left) and Spanish (right) infantry. The soldiers of both sides are very similar, and therefore the artist emphasized the long lances of the Spaniards. Soldiers under the French banner carry small white crosses on their chests and backs.

A fragment of the picture of the Tunisian campaign that confuses historians and experts - the arquebus is equipped with some kind of sighting device.

Chaos erupted in Italy. To restore balance, on April 31, 1495, Spain and the Habsburgs formed the Holy League, which was also joined by England and the Italian states. The Spanish commander (gran capitan) Fernando de Cordoba was the first to react and led his troops from Sicily to Naples. Charles VIII, fearing encirclement, left only a small garrison in Naples and with the main forces retreated to France. Charles's Italian campaign can serve as an illustration of a typical medieval raid without a prepared base and communications. This campaign began the first of six Italian wars that lasted until 1559.

After the French retreat, the Holy League collapsed, and the heir to the French throne, Louis XII, began planning a new campaign in Italy. He concluded an alliance with England and peace treaties with Spain and Venice. The Swiss Confederation allowed him to hire Swiss "reislaufers" (reislaufer, reisende Krieger - traveling, nomadic warriors, German) as mercenaries for his infantry. In July 1499, French troops crossed the Alps, and the war flared up again.

The Swiss and their long spears

Switzerland managed to defend its independence in the 15th century. The people lived freely in the highlands, and all conflicts were resolved with the help of swords, axes, halberds and spears. Only an external threat could force them to unite to defend independence. There were few shooters among them, but they learned to resist cavalry in field battles with the help of their long (up to 5.5 m) spears. In the Battle of Murten, they managed to defeat the best heavy European cavalry of the Burgundian Duke Charles the Bold at that time. The Burgundians lost from 6,000 to 10,000 soldiers in the battle, and the Swiss only 410. This success made the Reislaufers the most sought-after and highly paid mercenaries in Europe.

The Swiss were known for their cruelty, endurance and courage. In some battles they literally fought to the last man. One of their traditions was to kill panickers in their ranks. They went through tough drills, especially in the possession of their main weapon - a long spear. Training continued until each fighter became an integral part of the unit. They did not spare their opponents, even those who offered a large ransom for themselves. The hard life in the Alps made them excellent warriors who earned the trust of their employers. War was their trade. This is where the saying comes from: “No money, no Swiss.” If the salary was not paid, they immediately left, and did not care at all about the position of their employer. But with regular payment, the loyalty of the Swiss was ensured. At that time, long (up to 5.5 m) spears were the only effective weapon against cavalry. The infantry formed large, from 1000 to 6000 fighters, rectangular formations, similar to the phalanxes of the era of Alexander the Great. Armor was required for front-rank fighters. From the beginning of the 16th century, the spearmen began to be supported by arquebusiers. A three-part formation was common: vanguard - Vorhut, center - Gewalthaufen, rearguard - Nachhut. Since 1516, according to an “exclusive” agreement with France, the Swiss served as pikemen and arquebusiers. The long infantry spear had been known in Europe since the 13th century, but it was in the hands of the Swiss that it became so famous and, following the Swiss model, was used in other armies.

Photo from the Zurich Museum. Shows Swiss soldiers in armor from the first quarter of the 16th century. Particularly interesting are the pikemen, who demonstrate the three main ways of holding a pike. The only thing missing is the fourth one - horizontal, at chest level. To repel attacks of knightly cavalry, pikes rested on the ground.

Landsknechts and Spaniards

Halberdier (c. 1550). Some authentic engravings preserve images of German landsknechts - guards at the tent of the Spanish commander. They were, as in this image, armed with halberds. In the Spanish army, the halberd was a weapon and a distinctive sign of non-commissioned officers. In addition to its main function - blows and thrusts, the halberd could even out the ranks of soldiers in the ranks. Forming a battle formation was not an easy task and could take up to several hours. Three-quarter armor was typical of all European armies of the 16th century.

The standing army of the Holy Roman Empire was organized by Emperor Maximilian I in 1486. The infantrymen were called Landsknechts. At first they served the empire, but then they began to hire themselves to others. A typical unit under a captain (Hauptmann) consisted of 400 landsknechts, 50 of whom were armed with arquebuses and the rest with pikes, halberds or two-handed swords. The soldiers chose their non-commissioned officers themselves. Experienced veterans usually had better weapons and armor. They received a higher salary and were called “Doppelsoeldner” (Doppelsoeldner - double salary, German).

German Landsknechts ca. 1530 A contemporary wrote: “Their life is so terrible that only beautiful clothes bring joy to their hearts.” Apparently, the Landsknechts started the fashion for bright clothes.

In the 16th century, Spain became the leading military power in Europe. This happened mainly because it turned out to be the only state to the west of the Ottoman Empire with a regular army. "Regular" troops were constantly in military service and therefore received pay during the entire time. And Spain needed such an army, since throughout the 16th century it waged continuous wars on land and at sea. These campaigns were paid for by the wealth of the colonies of South and Central America.

The Spanish officers seemed to have stepped out of the pages of fashion magazines of the 60s and 70s of the 16th century.

One of the advantages of standing armies was that officers could gain experience over long periods of service. Therefore, Spain had the best officer corps at that time. In addition, a standing army can continuously develop its organizational structure and tactics and adapt them to the requirements of the time.

Musketeer of the early 17th century. Over his shoulder is a bandolier with ten wooden containers for ready-made cartridges, and on his belt are two powder flasks and a pouch for bullets.

Spanish captain (c. 1600). Spanish officers were professional soldiers whose careers developed according to their origin and military talent.

Pikeman officer. These were the ones who fought in the front ranks.

In the 16th century, Spanish troops fought in Italy and Ireland, France and the Netherlands, South and Central America, and Oran and Tripolitania in North Africa. For some time, Spain was closely associated with the Holy Roman Empire. The Spanish king Charles I was at the same time Emperor Charles V. In 1556, he renounced the Spanish throne in favor of his son Philip, and the emperorship in favor of his brother Ferdinand. At the beginning of the 17th century, Spain weakened economically and technically and at the same time was forced to confront new rivals, primarily England and France. Before the Thirty Years' War of 1618-48, or rather the Franco-Dutch-Spanish War, it still retained the status of a great power. But defeat by the French at Rocroi in 1643 was a blow from which Spain's military power never recovered.

Tertius

At the end of the 15th century, Catholic couple Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile expelled the Moors from Spain and began to transform the troops of their states into a single army. In 1505, 20 separate parts were formed - Coronelia or Coronelas (from the Italian colonelli - column). At the head of each was a “column commander” - cabo de coronelia. Each of these units included several companies, numbering from 400 to 1550 people. Since 1534, the three “columns” were united into one “tertia”. Four tercios formed one brigade, and seven formed one double brigade. Spain at that time belonged to southern Italy and Sicily, where the first tercios were formed. They received their names from the districts where they were formed: Neapolitan, Lombard and Sicilian. A few years later, another one was added to them - Sardinian. Later, some tercios were named after their commanders. From 1556 to 1597, King Philip II formed a total of 23 tercios to serve in Spanish-controlled lands. Thus, in the period 1572-78, there were four tercios in the Netherlands: Neapolitan, Flemish, Lüttich and Lombard. The strongest was the Neapolitan one, which included 16 mixed companies, consisting of pikemen and arquebusiers, and four purely rifle companies - of arquebusiers and musketeers. It is also known that the Sicilian and Lombard tertia consisted of eight mixed and three rifle companies, and the Flemish one - of nine mixed and only one rifle company. The number of companies ranged from 100 to 300 fighters. The ratio of pikemen and riflemen is 50/50.

Pikener (c. 1580). The Spaniards called the pike “senora y reyna de las armas - mistress and queen of weapons.” The respect for her was such that even the aristocrats did not disdain her. The Duke of Parma fought in 1578 at the Battle of Reymenam on foot with a pike in his hands. The length of the Spanish pike was approx. 20 feet (approx. 5 m). According to some reports, between 1571 and 1601, about half of all Spanish pikemen were dressed in "three-quarter" armor - that is, armor that covered 3/4 of the body surface. It provided protection against arquebus bullets fired from a distance of 200 m. The pikeman shown in the picture has a “morion” helmet, typical of the 2nd half of the 16th century.

The number of thirds ranged from 1500 to 5000 people, divided into 10 - 20 companies. It is known that some tercios intended for landing in England in 1588 had from 24 to 32 companies; the actual number of personnel is unknown. The record was recorded in 1570, when the Flemish Tertia numbered 8,300 soldiers, and the Sicilian and Lombard Tertia were strengthened to 6,600 in the same year.

Tertia (c. 1570)

The Dutch army at the Battle of Nieuwport (1600). The Dutch, led by Moritz of Nassau, had a double superiority in cavalry (3,000 versus 1,500 Spanish), which largely ensured their victory. The Dutch Army consisted of 16 small infantry units called regiments. Experience has shown that smaller and more mobile units have an advantage over bulky and clumsy thirds.

Organization

Around 1530, the tercios took their final form, and this was an important step in the development of infantry organization at that time. Tertia was an administrative unit and consisted of a headquarters and at least 12 companies, consisting of 258 soldiers and officers. Two companies were purely rifle companies, and in the remaining ten the ratio of pikemen and arquebusiers was 50/50. According to the Duke of Alba, the best combination was 2/3 pikemen and 1/3 riflemen. After 1580, the number of soldiers in companies decreased to 150, and the number of companies, on the contrary, increased to 15. The purpose of this was to increase tactical flexibility. Also, the number of pikemen soon decreased to 40%, and the proportion of musketeers in rifle companies increased from 10% to 20%. From the beginning of the 17th century, the number of pikemen was again reduced - to 30%. Since 1632, both arquebus companies were abolished.

Arquebusier (c. 1580). In the early stages, arquebuses were called escopeta, and hands, respectively, escopetero. This name is found in sources up to the beginning of the 17th century. The standard matchlock arquebuses were called "arcabuz con ilave de mecha", and later wheeled arquebuses, like the one shown in the picture, were called "arcabuz con ilave de rueda". The shooter in the illustration has a winding key suspended from his belt under the powder flask. When firing, the shooter rested the arquebus against his chest, which is why the butt has this shape. From about 1580, Spanish soldiers received material for clothing once a year. The colors could be anything, and the soldiers also took care of tailoring themselves, so there could be no question of any uniform in the modern sense. It was believed that free choice of clothing increased the morale of soldiers. For example, the soldiers of one of the thirds were nicknamed “church servants” because of their black clothes.

The tertia was commanded by a colonel - Maestre de Campo. The headquarters was called Estado Coronel. The deputy commander - Sargento Mayor (major or lieutenant colonel) was responsible for training personnel. In this he was assisted by two adjutants - Furiel or Furier Mayor. Each company (Compana) was headed by a captain (Capitan) and an ensign (Alferez). Each soldier, after five years of service, could become a non-commissioned officer (Cabo), then a sergeant (Sargento), after eight years - an ensign, and after eleven - a captain. The commander over several tercias bore the rank of Maestre de Campo general (Colonel General), and his deputy the title of Teniente del maestre de campo general. Over time, the tertia turned from a tactical unit into an administrative unit, although in some cases they acted as a single unit. Individual units of one or more terts often participated in battles. From about 1580, individual companies fought more and more frequently, united when necessary into improvised formations of up to 1,000 soldiers, called Regimentos (regiments) and bearing the names of their commanders. Many mercenaries, most often Germans, served in the Spanish army. The record year was 1574, when there were 27,449 mercenaries in the infantry and 10,000 in the cavalry.

Musketeer (c. 1580). Since the 1520s, the Spaniards used heavy arquebuses, which could only be fired from a bipod. Since the 1530s, the name muskets has been assigned to them. A musket was 2-3 times more expensive than an arquebus. In order for the shooter to absorb its recoil, rest it on the shoulder. To do this, the butt became straight. The mercenary Roger Williams, who served either the Spaniards or their Dutch opponents, said: “A hundred muskets are stronger than a thousand arquebuses.” He also believed that a musket could hit any horseman or infantryman at a distance of up to 500 paces, and no amount of armor would protect against a bullet fired from a distance of less than 500 paces. The English chronicler Joht Smythe in his book “Animadversions” (1591) wrote that the Spaniards open fire from a distance of 150-300 steps, and begin to cause any damage to the enemy from 500-600 steps. Bernardo de Mendoza wrote in 1595 that musket fire could be fired simultaneously by two ranks, with the first one firing from the knee. The musketeer in the illustration has two powder flasks: a large one with coarse, propellant powder, and a small one with finer, seeding powder. The wick was also worn on the belt in pieces 1-2 meters long and cut off as needed.

Tactics

An illustration from an officer's manual (c. 1600) depicts the different formations of a tercius in battle. This was impossible without many years of training and experienced commanders. Today it is impossible to say how realistic and effective these maneuvers are in battle.

A common Spanish tactic was to form the pikemen in a 1/2 aspect ratio rectangle, sometimes with an empty space in the middle. The long side was facing the enemy. At each corner there were smaller rectangles of riflemen - “sleeves”, like the bastions of a fortress. If several thirds took part in the battle, then they formed something like a chessboard. Arranging soldiers into regular rectangles was not an easy task, so tables were invented to help officers calculate the number of soldiers in ranks and ranks. Up to 4-5 thirds took part in large battles. In these cases, they were positioned in two lines to provide fire support to each other without the risk of hitting their own. The maneuverability of such formations was minimal, but they were invulnerable to cavalry attacks. Rectangular formations made it possible to defend against attacks from several directions, but their movement speed was very low. It took many hours to form an army into battle formation.

The size of the construction was determined by the deputy. commander He calculated the number of soldiers in the ranks and ranks in order to obtain a front of the required width, and from the “extra” soldiers they formed separate small units.

Calculation tables for planning the formation and tactics of a third, consisting of individual small units, have been preserved to this day. Such complex constructions required mathematical precision and intensive long-term drill. Today we can only guess what it really looked like.

Then, recognizing that smoke has the property

Rise to the heavens - fill them with

A huge ball and fly away like smoke!

Edmond Rostand "Cyrano de Bergerac"

What is unusual about the 17th century? Until now, there is no unity among historians as to which era it should be attributed to. Sometimes it is seen as the decline of the Middle Ages, sometimes as the dawn of modern times. The century began when knights in full armor already looked ridiculous, but had not yet disappeared from the battlefields, and bayonets were already shining through the explosions and puffs of powder smoke.

During this strange time lived Cardinal Richelieu and d’Artagnan; philosopher, poet, soldier, atheist and science fiction writer, who later became a literary character himself, Cyrano de Bergerac; mathematician and rationalist thinker Rene Descartes; physicist and part-time author of the first version of the “New Chronology” Isaac Newton.

Every whim for your money

The heroes of the “transitional era” are hired arquebusiers, halberdiers and pikemen. Pikemen occupied a privileged position

During the 16th-17th centuries, traditional feudal armies were increasingly replaced by mercenary armies. Which, however, did not yet mean the appearance of a regular army. On the one hand, kings consistently preferred completely loyal (as long as salaries were paid on time) landsknechts to willful vassals. Such progressive transformations as are necessary for the development of capitalism, such as the elimination of feudal fragmentation and the emergence of centralized nation states, would have been impossible without the concentration of all military power in the hands of the ruler. But, on the other hand, capitalism was still very poorly developed. And the king could not support a standing army with the taxes collected. Mercenaries (preferably foreigners, to ensure their independence from the local nobility) were recruited only in case of war, usually for a period of six months.

To speed up the recruitment process, soldiers were hired not “one by one,” but as entire teams working together. Already with their own commanders and, naturally, with weapons. In the intervals between hires, “gangs” (regiments) of Landsknechts usually stood in the territories of the dwarf German states, engaged in combat training and recruiting personnel. The movements of unemployed, and therefore “neutral” regiments across Europe, as well as their legal status in their locations, were stipulated by special laws at that time.

Musketeer equipment: a musket, a support, a dagger, a horn with gunpowder for the regiment, several charges or a horn with gunpowder for shooting. And no cavalry boots - jackboots.

The mercenary soldier received regular pay from his commanders and was trained to act in the ranks, but that’s all. He acquired weapons, food and equipment himself. He hired his own servants and took care of transporting his property (as a result of which there were more non-combatants in the army than soldiers). He himself also paid for fencing lessons if he wanted to learn how to wield a weapon. Order and combat effectiveness were maintained by kaptenarmus (armourer captains), who ensured that the fighters had the weapons and equipment required by the state. Those who drank their lances and swords were threatened with immediate dismissal.

Wanting to win the regiment over to his side, the employer organized a review. At the same time, not only weapons were taken into account, but also the average height of the soldiers, as well as their appearance. Soldiers who looked like robbers or vagabonds were not counted, because there were fair fears that they were exactly what they seemed... Of the fighting qualities, only combat training was tested, on which the ability to use pikes depended, and the ability of the musketeers to stuff their “pipes.”

The procedure for loading a musket: separate the wick, pour gunpowder into the barrel from the charger, remove the cleaning rod from the stock, hammer the first wad from the pouch with a cleaning rod, hammer a bullet with a cleaning rod, hammer the second wad, remove the cleaning rod from the stock, open the shelf and pour gunpowder from the horn onto it, close shelf, attach the fuse... At that time they rarely fired more than one salvo per battle.

The extravagance of the military costume was largely due to the low development of the art of fencing. The blade's blows were almost never parried. Enemy attacks were repelled with a buckler shield or... a sleeve

In addition to the elite mercenaries, who constituted the main striking force of the army in the 17th century, there was also a broad category of fighters “for the numbers.” As soon as the war began, “willing people” joined the army for a nominal fee: Italians, Germans, Gascons, Scots, as well as adventurers of a nationality that was no longer visible to the eye. Their armament was very diverse: cutlasses, dirks, claymores, halberds, spears, self-propelled guns, crossbows, bows, round shields. Some also brought riding horses of the Rocinante class.

Mercenaries of this type lacked organization. And it was impossible to bring it quickly. After all, the king did not have “extra” sergeants and officers. Already on the spot, detachments were spontaneously formed from volunteers, which rather deserved to be called gangs.

Due to their zero combat value, the tasks of these formations were usually reduced to protecting rear areas and communications.

In peacetime, the military forces of the state were limited to the guard - in fact, the king's bodyguards. Textbook examples of such units were the royal musketeers and the cardinal's guards, known from the works of Dumas. The no less famous (albeit exaggerated by the writer) enmity between them was due to the fact that the guards were engaged in maintaining order in Paris (there were no police in other cities yet), and the musketeers, in their free time from His Majesty’s guards, wandered the streets and committed hooliganism.

Eastern European style musketeers

The Guard was not disbanded in peacetime, but in other respects its fighters were no different from mercenaries. In the same way, they acquired equipment themselves (with the exception of a uniform cloak) and themselves learned to wield weapons. These detachments were intended to perform ceremonial and police functions, and therefore their combat effectiveness did not withstand practical tests. So, in the very first real battle, both companies of the royal musketeers rushed into a mounted attack with swords drawn, were defeated and disbanded. D’Artagnan’s comrades did not know how to fight either on horseback or on foot (that is, swing the “caracole” with muskets).

Artillery

Cannons of the 16th-19th centuries were secured in position with ropes to the wheel hubs or to rings on the carriage to stakes driven into the ground. After the shot they rolled back, extinguishing the recoil energy.

The “Achilles heel” of 17th-century artillery was not the material part, but the primitive organization. For each gun there were up to 90 servants. But almost all of them were non-combatant workers.

The cannon and ammunition were transported by hired or mobilized civilian carriers, and the position for it was prepared by navvies. Only before the battle were several soldiers sent to the gun, often without any training. They could load a cannon and fire it (it wasn't difficult). But a single gunner aimed each of the battery’s 12 guns in turn.

As a result, the artillery performed well in defense. Fortunately, the cavalry of that era had completely lost their fighting ardor, and the battles were creeping up slowly and sadly. But the guns were powerless in the offensive. They could not change position after the start of the battle. Neither the drivers nor their horses would simply go under fire.

Infantry

By the beginning of the 17th century, infantry weapons were quite varied. The main force of the army was armored detachments of pikemen with 4-5-meter “Habsburg” peaks. The functions of light infantry were performed by halberdiers and shooters with arquebuses or crossbows. Round shields (including “bullet-proof” roundels), cutlasses and swords remained in use. Long bows were also kept in service. By the way, they were used by the British back in 1627 in the battles for the very same La Rochelle, under whose walls d’Artagnan fought as a hero.

The basis of tactics remained the offensive in “battles” - compact formations of 30 by 30 people, capable of repelling a cavalry attack from any direction. Halberdiers and riflemen covered the pikemen.

Pikeman in position to repel a mounted attack

Back in the 16th century, guns became the main threat to infantry. A cannonball hitting a battle would result in huge losses. Coverage was also a danger - after all, the unit's peaks could only be directed in one direction. Therefore, attempts were made to improve the system. In Spain, the “tertia” was invented: building 20 rows in depth and 60 along the front. It was more difficult to get around it, and the number of victims of artillery fire was somewhat reduced.

But the formation of columns of 30 people in depth and only 16 along the front had greater success. It would seem that 4 columns were just as easy a target for enemy cores as 2 battles. But first impressions are deceiving. It was easier for the column to choose a road, and it covered the area under fire much faster. In addition, until the end of the 19th century, guns did not have a horizontal guidance mechanism. Focusing on the furrows left on the ground by ricocheting cannonballs, the commander could try to move his squad between the lines of fire of two adjacent guns. Advancing in columns is well established and has been practiced for over 200 years.

From culverin to cannon

Russian guns of “skinny” proportions

Already by the beginning of the 16th century, technology made it possible to drill out the muzzle channel in a solid bronze blank, and not to cast the barrel immediately in the form of a hollow pipe, as was the case in the bombard era. Accordingly, it was possible to do without a screw-in breech and load the gun from the barrel. Guns have become much safer.

However, the quality of the casting still left much to be desired. They were afraid to put a lot of gunpowder into the gun. In order not to lose too much in the initial speed of the projectile, the barrel was lengthened to 20-30 calibers. In view of this, even after the invention of “pearl” - granular - gunpowder, loading a cannon took a long time. The cooler of “siege power” generally had a 5-meter barrel, “incompatible with a ramrod.” The scattering of buckshot was also insufficient. Therefore, for self-defense of the battery, in addition to 8-10 culverins, 2-4 falconettes were included in it.

Mass casting of guns with a powerful charge, but with a barrel shortened to 12-14 calibers, was established during the 17th century.

Cavalry

Knightly armor, however, mainly as tournament and ceremonial equipment, continued to be improved until the beginning of the 17th century.

In case of war, the king could still count on the militia of the cities (whose role, however, was limited to protecting the walls) and loyal vassals fielding cavalry. After all, no one has canceled the military duty of the nobility. But the military significance of chivalry began to decline already from the beginning of the 16th century. Times have changed. The landowners now calculated the income from their estates and no longer sought to participate in wars - except according to tradition. And the kings themselves were least eager for the magnates to begin recruiting personal armies.

But cavalry was still needed. Therefore, the rulers began to resort to the services of hired reiters.

“Reitar” is the third (after “ridel” and “knight”) attempt by the Russians to pronounce the German word “ritter” - horseman. In European languages there is no difference between a knight and a reitar. She didn't actually exist. Both the knightly and the Reitar cavalry consisted mainly of poor nobles who did not have their own estates. Only before they served as vassals to some large feudal lord for in-kind allowance, and in the 16th-17th centuries for money - to anyone who would pay it.

Hiring reiters, however, rarely justified itself. Already from the 16th century, cavalry was in deep crisis. The long peaks left her no chance. The most effective tactical technique - hitting - became impossible. In Europe they did not know how to use cavalry for flanking. And the heavy knight's wedges were not suitable for maneuvers.

Eastern European heavy cavalry in the 17th century retained spears in service (since they rarely had to deal with pikemen). In general, it was much more combat-ready than the Western one

A temporary solution was found in replacing the spears with long wheeled pistols. It was assumed that the rider would be able to shoot infantry from a safe distance of 5-10 meters. The cavalry leisurely riding across the battlefield and stopping to shoot and load certainly made an indelible impression. But there was no benefit from it. A heavily armed mounted rifleman is nonsense. Compared to the Asian horseman, the “firearm” reitar turned out to be ten times more expensive and worse in approximately the same proportion. Because it did not have the advantages of light cavalry (speed and numbers).

The increasingly widespread use of firearms by infantry made leisurely attacks “with a pistol drawn” completely impossible. The cavalry finally began to be transferred to the flanks in order to be used for attacks with melee weapons on the enemy’s light infantry. But even there she did not achieve success, both due to slowness and because... the reiters rode poorly! The cavalry rushed to the attack at a walk, or at best at a trot.

The “knightly” culture of Western Europe, closely associated with the art of equestrian combat, fell into decline. Order and royal equestrian schools, in which knights were taught to attack with a wedge, no longer existed. Meanwhile, the “stirrup to stirrup” gallop and horse riding require good training of both riders and horses. The reiters had nowhere to buy it.

The horsemen of the early 17th century did not even have weapons that they could use while moving. The cavalry sword, of course, was longer and heavier than the infantry one, but it was impossible to cut a helmet with it. An attempt to stab an opponent at a glance is fraught not only with the loss of the blade, but also with a broken wrist.

Core

Since stone cores were carved by stonemasons, not sculptors, they were not distinguished by the geometric rigor of their form.

The problem of the projectile became a “tough nut to crack” for artillerymen of the 16th-17th centuries. Stone cores, which were in use in the Middle Ages, no longer corresponded to the spirit of the times. Being released from the culverin, when they hit the ground they split and did not give a ricochet. Iron blocks wrapped in rope flew much further, but very inaccurately. From the point of view of firing range, the best material was lead. But when it hit the ground or a fortress wall, the soft metal was flattened into a thin pancake.

The optimal solution was to use bronze, which combined hardness and elasticity with manufacturability. But such shells would be too expensive. The find turned out to be cast iron - a cheap and suitable metal for casting. But its production required blast furnaces, so even at the beginning of the 19th century, Turkey, for example, experienced a shortage of cast iron cores.

By the way, the guns themselves could be cast from cast iron, although with the same power their barrels turned out to be 10-15 percent heavier than bronze ones. For this reason, bronze remained the preferred "artillery metal" until the end of the 19th century. Cast iron made it possible to produce a lot of cheap weapons for arming ships and fortresses.

Reforms of Gustavus Adolphus

In Europe, a support equipped with a blade and turned into a reed was called a “Swedish feather”. Although the Swedes themselves soon abandoned supports altogether

One might get the impression that the armies of the 17th century were cumbersome, ineffective and overly complex. For the rulers of that era, in any case, it worked out that way.

Technological progress played an important role in this. The guns fired more and more often, infantry losses grew. Finally, the gradual displacement of arquebuses by muskets, the range of effective fire of which exceeded 200 meters, made it impossible to cover the battle with halberdiers. They would have to move too far away from the pikemen, and who would then protect them from the enemy cavalry?

In the 30s of the 17th century, the Swedish king Gustav Adolf decided to reform the army, radically simplifying the organization. Of all the infantry branches - pikemen, arquebusiers, crossbowmen, halberdiers, musketeers, swordsmen - he retained only two: musketeers and pikemen. To reduce losses from enemy fire, shallower formations were adopted: for musketeers in 4 rows instead of 10, and 6 instead of 20-30 rows for pikemen.

To increase mobility, the pikemen were deprived of protective equipment, and the pikes themselves were shortened from 5 to 3 meters. Now the pike could not only be held at the ready with difficulty, holding the blunt end under the arm, or rested on the ground, turning it into a spear placed in the path of the enemy cavalry, but also strike with it. Muskets were also significantly lighter and began to be used without support.

In Russia, rearmament according to the European model began not under Peter I, but under Alexei the Quiet. He just carried out reforms quietly

The listed measures, of course, deprived the army of Gustavus Adolphus of immunity to cavalry attacks. But, given the fighting qualities of the reiters, the Swedes did not risk anything. For his part, the king took steps aimed at strengthening the Swedish cavalry. Horsemen were forbidden to use armor (by that time, other nations still had little difference from knightly armor). They began to be required to be able to attack at a gallop, in formation, with melee weapons. The Swedes rightly believed that the problem was not in the pikes, but in the insufficient maneuverability of the cavalry, unable to bypass the battles.

Finally, in Sweden, for the first time, the army was transferred to a permanent basis, turning into a semblance of the guards of other states. Of course, this cost the Swedes a pretty penny, but the treasury was regularly replenished with indemnities from the vanquished.

“Reformed” Sweden, sparsely populated, having practically no cities at that time and forced to buy weapons (but smelting half of the iron in Europe and monopolistically supplying England and Holland with timber for the construction of ships), unleashed real terror on the continent. For a century there was no sign of the Swedes. Until they saw Kuzka’s mother near Poltava.

Regimental guns

Perhaps the most radical innovation of Gustavus Adolphus was the creation of regimental artillery, which created a real sensation on the battlefields. Moreover, the design of the guns did not contain anything new: they were the most ordinary falconets with a caliber of 4 pounds. Sometimes leather tools were even used.

The organization was revolutionary. Each of the cannons received a team of powerful state horses, constantly kept in the royal stables and accustomed to the roar of shots and the sight of blood. And also a crew of selected soldiers who masterfully wield a ramrod and a banner. Moreover, one officer no longer accounted for 12, but only 2 guns.

As a result, the guns, which until now had only held the defense in a previously prepared position, were able to advance ahead of the infantry and even pursue the enemy, showering them with grapeshot. If the enemy tried to approach, the limbers drove up and took away the guns.

* * *

In military affairs, the 17th century ended the same way it began: ahead of schedule, contrary to the calendar. In the 80-90s, a new wave of rearmament swept across Europe. Lightweight muskets and “Swedish” pikes were quickly replaced by uniform flintlock rifles with a bayonet. Over the course of several years, the armies acquired the appearance that remained virtually unchanged until the first third of the 19th century. And this was already a different era.

Both Lützen and the death of the king, the position of the anti-Habsburg coalition seriously deteriorated. The Imperial commander Wallenstein gradually regained the lost territories, and even his assassination could not affect the course of the war. It seemed that the Habsburgs were about to win. The French, desperate to decide the outcome of the war by proxy, were forced to enter the war, which marked the beginning of a new stage in the Thirty Years' War. From that moment on, the war completely lost its religious overtones, as the French Catholics took up arms against the Spanish Catholics, joining the Protestants.

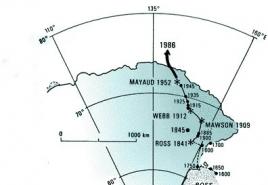

Route tercios from Spain to Flanders. (wikimedia.org)

Year after year, the parties tried unsuccessfully to turn the tide of the war through sieges, battles and negotiations. Suddenly, in December 1642, the first minister of France, Richelieu, died (the grief of the Parisians can be assessed by the songs that circulated among the people after the death of the cardinal: “He left and now rules hell, and he has devils with halberds on guard”).

At the beginning of the next year, the already middle-aged Louis XIII became seriously ill. Madrid considered this a good sign and prepared for active action against France in the Spanish Netherlands. If the Spaniards prevailed in the general battle, one could hope for France's withdrawal from the war and the victory of the Habsburgs.

Start of the campaign

The Spanish army was commanded by Francisco de Melo. To invade France, he concentrated about 30 thousand people: Spaniards, Italians and Germans. The Spanish infantry (tercio) was particularly distinguished by its high qualities, terrifying its enemies for more than a century. The weaknesses of the Habsburg army were the lack of cavalry, outdated organization and heterogeneity of composition.

In mid-May, the king died and the throne was transferred to five-year-old Louis XIV. At the same time, the Spaniards crossed the border and besieged the small Ardennes fortress of Rocroi, which was defended by a tiny garrison. The young French commander, the Duke of Enghien, moved to help the besieged.

From the Condé family

It is worth mentioning separately about the personality of the commander. Louis de Bourbon-Condé was born in 1621 in Paris and belonged to the junior branch of the House of Bourbon. While his father, Prince Condé the Elder, was alive, the young man was called the Duke of Enghien.

In his youth, Louis was distinguished by a violent temper and eccentric antics, shocking the French nobility, but Richelieu was able to discern military talent in him and, before his death, convinced the king to appoint the young man as commander on the Flemish border. Interestingly, shortly before his death, Louis XIII regained consciousness and told Condé the Father that he had seen in a dream how his son “won the greatest victory.” Just a few days later, the king's dream was destined to come true.

Engraved portrait of Prince Condé the Younger. (wikimedia.org)

On the eve of the battle

On the evening of May 18, French troops lined up on the field in front of Rocroi. There was no consensus among the commanders whether it was worth engaging in a full-scale battle: the experienced commander L’Hôpital suggested avoiding the battle by cutting off the Spaniards’ communications, but the Duke of Enghien was adamant. The French troops had excellent cavalry, which was located on the wings of the battle formation. In the center the infantry was formed in three lines: the battalions stood in a checkerboard pattern.

Artillery was placed in front of the infantry. A total of 15 thousand infantry and 7 thousand cavalry with 12 guns. The Spaniards lined up in a mirror image: infantry, gathered in huge columns-tertia, in the center in three echelons, cavalry on the flanks. In addition, a thousand musketeers occupied the forest on the left flank. This ambush regiment was supposed to attack the French cavalry when it rushed to attack the Spanish wing. In total, the Spaniards had 16 thousand infantry and 5 thousand cavalry with 18 guns. Melo was expecting reinforcements to arrive and therefore decided to stick to defensive tactics

Scheme of the Battle of Rocroi. (wikimedia.org)

In the middle of the night, a Spanish defector appeared in the French camp and told Conde that Melo was expecting reinforcements any minute, and that Spanish musketeers were hiding in the forest on the right flank. The Duke decided to act immediately. Under the cover of artillery, he cleared the forest of Spanish riflemen, which Melo did not know, believing that his left flank was reliably protected. Soon dawn came, the Spanish cannons opened fire on the enemy and quickly suppressed the French artillery, but Condé Jr. had already led his troops into the attack.

La Ferte, the commander of the first echelon of the left wing, attacked the Spanish cavalry on his flank too zealously - the galloping horsemen mixed up and reached the Spaniards' lines in a disorganized crowd and were immediately crushed by Melo's horsemen. Neither the counterattack nor the introduction of the second line into battle helped matters - the left flank was destroyed and La Ferte was captured. At the same time, the Italian tercios rushed to attack the French battalions. The French infantry found itself in a difficult situation: the enemy cavalry was on the left, the French guns were captured and firing at point-blank range, the enemy's thirds were pushing back the infantrymen. By 6 a.m. Condé's situation became critical.

Radical fracture

The only place on the battlefield where the Duke of Enghien was successful was on the right wing. Having cleared the forest of the Spaniards, he sent the cavalry to bypass the Spaniards, and when they turned to repel the attack, Conde the Younger himself struck the exposed flank of the Spanish cavalry, which fled. Immediately the young commander decided on a daring maneuver.

With his cavalry, he swept between the echelons of Habsburg infantry and struck in the rear the infantry of the first line and the Spanish cavalry, which was pressing on his infantry. At this time, the French brought reserves into the battle, managed to defeat Melo's Italian tercios and recapture several guns. The remaining five Spanish tercios remained combat-ready, their commander Fontaine formed a square and, not realizing the real state of affairs, instead of retreating from the battlefield in an orderly manner, he began to expect a French attack.

Soldiers of the Spanish Tertia. Still from the film “Captain Alatriste”. (wikimedia.org)

The Duke of Enghien, remembering the reinforcements rushing to the Spaniards, reorganized his troops to attack Fontaine. Three times the French approached the Spanish square and three times were repulsed. The Tertii were like a bastion, consisting of people, bristling with pikes and muskets. Letting the attackers get closer, the Spaniards rolled out artillery and fired grapeshot at point-blank range. But the forces of the defenders gradually melted away, and there was a shortage of gunpowder and ammunition. Soon the second of the remaining tercias "Garcias" laid down their weapons. Only the Albuquerque third held the defense, but even there a white flag loomed. The Spaniards mistook the detachment of the ducal retinue, which approached to accept surrender, for a new attack and opened fire. Conde Jr., having ensured the interaction of all branches of the military, continued the battle, soon breaking the resistance of the Spaniards, whom he treated very humanely: the last defenders retained their banners and swords.

"The Battle of Rocroi. The last third" Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, 2011. (wikimedia.org)

End of the battle

When Spanish reinforcements arrived on the battlefield, it was all over for Melo. The flower of the Spanish infantry, which constituted national pride, remained lying near the walls of the small Ardennes fortress. The Spaniards lost about half of the army: 7-8 thousand killed and wounded and about 4 thousand prisoners. The French captured artillery and convoys. However, the winners themselves did not fare well: the French lost at least 5 thousand. people killed and wounded.

Count of Enghien on the battlefield of Rocroi. (wikimedia.org)

The Battle of Rocroi is one of the glorious pages in the history of French weapons, but nevertheless did not lead to peace. There were still five years ahead of the Thirty Years' War, which would end only in 1648 with the victory of France; Mazarin would conclude peace with Spain only in 1659. In this battle, the need for closer interaction between the cavalry, which played an active role in the battle, and the infantry was clearly demonstrated. Under Rocroi, the talent of one of the most controversial and remarkable commanders of France - the Duke of Enghien, the future great Condé, comrade-in-arms and adversary - was clearly revealed. In addition, this victory became the first battle of the reign of the new king, opening the glorious era of Louis XIV. The Spanish infantry showed miracles of courage and resilience, demonstrating their best qualities, but their veterans were left lying on the battlefield at Rocroi, and their glory would soon fade at the Battle of Dunkirk (1658). The old Spanish tercio gave way to a more flexible linear system.