House by the road read summary. The poem “House by the Road” is a story about the fate of a peasant family

Poetry of the post-war and war periods sounds completely different from peacetime works. Her voice is piercing, it penetrates into the very heart. This is how Tvardovsky wrote “House by the Road”. Summary of this work presented below. The poet created his poem not only to express the pain of the destinies of his contemporaries destroyed by the war, but also to warn his successors against a terrible tragedy - war.

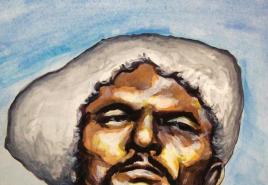

About the poet

Vasily Trifonovich Tvardovsky was born in 1910 in the Smolensk province Russian Empire. His parents were educated people, my father read classics of Russian and world literature to his children from early childhood.

When Vasily was twenty years old, the period of repression was in full swing. His father and mother fell into the millstones of the revolution and were exiled to the north of the country. These events did not break the poet, but they put him at a crossroads and made him think about whether the raging revolution was really necessary and just. Sixteen years later, his peculiar utopia was published, after which the poet’s works began to be published. Alexander Trifonovich survived the war, his “Vasily Terkin” is about this. About the war and "Road House" summary Tvardovsky loved to retell even before the poem was published.

The history of the poem

The idea and main strokes of the poem were born in 1942. It is not known exactly why Tvardovsky did not finish his “Road House” right away. The story of the creation of the poem is most likely similar to the stories of other post-war and war works. There is no time for poetry on the battlefield, but if its idea and creator survive, then the lines carried through a hail of bullets and explosions will certainly be born in days of peace. The poet will return to the work four years later and complete it in 1946. Later, in his conversations with his wife, he would often remember how he thought about a dilapidated house by the road that he once saw - how he imagined who lived in it, and where the war had scattered its owners. These thoughts seemed to take shape themselves into the lines of a poem, but there was not only no time to write it, but also nothing to write it on. I had to keep in my thoughts, as in a draft, the most successful quatrains of the future poem, and cross out the not entirely successful words. This is how Tvardovsky created his “House by the Road”. See the analysis of the poem below. But it should be said right away that it does not leave anyone indifferent.

"House by the Road": summary. Tvardovsky about the war. The first and third chapters of the poem

The poem begins with the poet addressing the soldier. It was about him, about a simple soldier, that Alexander Tvardovsky wrote “House by the Road.” He compares the warrior’s protracted return to his wife with his completion of the poem that was waiting for him “in that notebook.” The poet talks about seeing an empty, dilapidated soldier’s house. His wife and children were forced to leave, and after the end of the fighting she returned home with the children. The author calls their poor procession “the soldier’s house.”

The next chapter tells about the last peaceful day of the soldier, when he mowed the grass in the garden, enjoying the warmth and summer, anticipating a delicious dinner in a close circle at the family table, and so with a scythe they found him with news of the war. The words “the owner did not mow down the meadow” sound like a bitter reproach to the war that cut short the owner’s affairs. The wife mowed the orphaned meadow, secretly crying for her beloved husband.

The third chapter of the poem “House by the Road” is ambiguous; Tvardovsky himself conveyed a summary of it with difficulty. She describes the hardships of war - soldiers in battle and women in unfeminine labor, hungry children and abandoned hearths. The long paths that a soldier mother with three children is forced to travel. He describes the fidelity and love of his wife, which peacetime were manifested by cleanliness, order in the house, and in the military - by faith and hope that the loved one will return.

The fourth chapter begins with a story about how four soldiers came to a house near the road and said that they would put a cannon in the garden. But the woman and the children need to leave here, because staying is reckless and dangerous. Before leaving, the soldier asks the guys if they have heard about Andrei Sivtsov, her husband, and feeds them a hearty hot lunch.

Chapter five describes the eerie picture of captured soldiers walking. Women look into their faces, afraid to see their relatives.

Chapters six to nine of the poem

At the end of the war, "House by the Road" was published. Tvardovsky retold the summary more than once to his loved ones, describing his experiences during the war.

Chapter six shows Anyuta and Andrey. The roads of war brought him home, just for one night. His wife sends him on the road again, and she and the children leave their home and walk through the dust of the roads to protect the kids.

Chapter seven tells about the birth of the fourth child - a son, whom the mother names Andrei in honor of his father. Mother and children are in captivity, on a farm besieged by the Germans.

A soldier returns from the war and sees only the ruins of his home near the road. Having grieved, he does not give up, but begins to build a new house and wait for his wife. When the work is finished, grief overcomes him. And he goes to mow the grass, the one he never had time to mow before he left.

Analysis of the work

Tvardovsky's poem "House by the Road" talks about broken families scattered across the earth. The pain of war sounds in every line. Wives without husbands, children without fathers, yards and houses without an owner - these images run like a red thread through the lines of the poem. After all, in the very heat of the war, Tvardovsky created his “House by the Road”. Many critics have analyzed the work, but they are all sure that the work is about the destinies of people tragically broken by the war.

But not only the theme of separation in its not entirely familiar recreation (it is not the wife at home waiting for the soldier, but he, grieving and rebuilding the house, as if restoring his former, peaceful life) is heard in the poem. A serious role is played by the mother’s appeal to her newborn child, her son Andrei. The mother, in tears, asks why he was born in such a turbulent, difficult time, and how he will survive in the cold and hunger. And she herself, looking at the baby’s carefree sleep, gives the answer: the child was born to live, he does not know what war is, that his destroyed home is far from here. This is the optimism of the poem, a bright look into the future. Children must be born, burned houses must be restored, broken families must be reunited.  Everyone must return to their house by the road - this is what Tvardovsky wrote. Analysis and a summary of the poem will not convey its fullness and feelings. To understand the work, you must read it yourself. The feelings after this will be remembered for a long time and will make us appreciate peacetime and loved ones nearby.

Everyone must return to their house by the road - this is what Tvardovsky wrote. Analysis and a summary of the poem will not convey its fullness and feelings. To understand the work, you must read it yourself. The feelings after this will be remembered for a long time and will make us appreciate peacetime and loved ones nearby.

Attention, TODAY only!

- M. Yu. Lermontov “The Fugitive”: a summary of the poem

- Nekrasov"; Railway";: summary of the poem

- A.T. Tvardovsky, “Vasily Terkin”: analysis of the poem

- Poem by A.T. Tvardovsky "Vasily Terkin". Image of Vasily Terkin

- Poem by A. T. Tvardovsky “By Right of Memory”. "By right of memory": summary

LIFE-DEATH ANTINOMY AND ITS ITS EMBODIMENT IN THE POEM OF A.T. TVARDOVSKY “HOUSE BY THE ROAD”

S.R. Tumanova

Department of Russian Language Faculty of Medicine Russian University Friendship of Peoples St. Miklouho-Maklaya, 6, Moscow, Russia, 117198

The article is devoted to the analysis philosophical problems life and death in the poem by A.T. Tvardovsky "House by the Road". The article discusses the motives of home, road, family, father, mother, love, nature, child in a situation of death during the Great Patriotic War, embodied in artistic images poems.

Keywords: antinomy, Tvardovsky, creative consciousness, creative motives.

The duel of life and death in all its meanings was for Tvardovsky the main event and leitmotif of his entire life and at different stages, depending on external circumstances, was internally resolved in different ways. During the war years, and this is understandable, after what was seen and felt first in the Finnish “unfamous”, and then in the Great Patriotic War, from an abstract thought it turns into a real everyday situation.

Reflections on life and death go in several directions. One of them was realized in the poem “Vasily Terkin”, the other, growing out of “Torkin”, became the basis of the poem “House by the Road”.

Home, road, family, father, mother, love, nature, child - these images-motives live in the poem between two extreme points - between life and death.

The themes and images of pre-war poems and lyrics turn out to be those powerful sprouts that subsequently give rise to huge fruit-bearing trees. And in the lyrics of the war years and in “Vasily Tyorkin” the motives for Tvardovsky’s future works are laid down. So the poem “House by the Road” grows out of “Vasily Terkin”.

Critics noted a turning point in the evolution of Tvardovsky the lyricist, starting in 1943, when notes of tragedy began to sound more and more strongly in his poetry. The increase in tragedy in literature became possible due to the change in the course of the war and increased optimism in society. Back in 1942, Tvardovsky wrote down words in his “Workbooks” in which he expressed the whole idea of the future poem: “We need to tell strongly and bitterly about the torments of a simple Russian family, about people who long and patiently wanted happiness, whose lot has fallen to so many wars, revolutions, trials." Tvardovsky wanted the house by the road to become a symbol recognizable to everyone who lost a home in the war. The name “House by the Road” was supposed to emphasize not the separateness of the house, but, on the contrary, its community.

Motives of home and road are central to many art worlds. But they are deciphered differently, depending on the content of ideas

and the moods of word artists. “In folklore, a “road house” is a place where people and evil spirits traditionally meet, their world with someone else’s world, open to the coming of both evil and good. For the owners of the house, this place becomes a test, as a person comes face to face with temptation.”

In Tvardovsky’s work, the house and the road are key motifs. Concrete, earthly concepts, absorbing all the meanings behind them, acquire philosophical overtones from Tvardovsky and become symbols of life. The combination of the house and the road was his creative discovery, making it possible to expand the meaning of each of the images. For a poet, home means that foundation of existence, without which life is impossible. The road implies movement, and therefore also represents life.

During the war, these motifs acquire new semantic shades. War with all its cruelty falls on a house, the loss of which is terrible especially for the owner, it is equal to the deprivation of life. During the war, the images of the house and the road merge and replace each other. The house turns out to be near the road and on the road, and the road becomes home and at the same time the enemy of the house, because it leads away from home to a foreign land. And although the house lost its walls and roof, it remained a home in the most important sense of kinship, relationships in the family:

But your house is assembled, it is obvious.

Build walls against it

Add a canopy and porch -

And it will be an excellent house.

“Perhaps the theme of family contains the answer to Tvardovsky’s life-affirming, harmonious worldview,” writes V.M. Akatkin, - his special epic lyricism? Grandfathers and grandchildren, father, mother and children, family, country, people - these are the supporting, essential meanings of all his work, his entire poetic mythology." The poem “House by the Road” reveals the meaning of human life. That’s why the poem tormented Tvardovsky. In “Vasily Terkin” everything is explainable and understandable: a soldier is at war, he must give his life for his homeland. Here the question arises: what is the meaning of human life if everything is destroyed and there is no home?

“Be alive” - this is how they greet a soldier who returns from captivity. In the very first chapter of the poem, the words “live”, “living”, “life”, “living” sound like a spell, as if life itself depends on their utterance. Life here is associated with the house, with the construction of a new house, in which “to live and live, ah, to live and live!” But this “ah” is a sad sigh (and behind it one can see the same sad shaking of the head) - a feeling of impending disaster. Building a house presupposes life, so smells and colors also become symbols of life:

And I would sing about that life,

About how the construction site smells like gold shavings again,

Live pine resin.

Another important motif in the poem is the motif of motherhood. In Tvardovsky’s work, he turns out to be the tragic note that sets the tone, and the node in which the most sincere is connected with the universally significant. During the war years, the motive of motherhood is filled with new content. Mother is the personification of perseverance, courage, the image grows into a symbol: mother-homeland, mother-earth. A mother’s feeling is always heightened, it is aimed at protecting her children, which is why the “great instinct for war” comes to a woman-mother earlier, it is in her blood: “My mother managed to pass it on to her by inheritance.” The mother gives life, therefore in literature her image always has a symbolic meaning of life. “And is it really so important,” writes Yu.G. Burtin - in this case, who is she, this woman: a collective farmer or a city dweller, Russian or, say, Latvian - and much more, which under different circumstances could have been the most significant and important for us and for her? One thing is important: she is a Wife and Mother - in the face of war and death."

She confronts death and defeats it, so strong is a mother’s love. “In full hunt”, “in full soul”, “from the heart” the poem is written. This is how the poet openly expresses in his letters his attitude towards the work, his internal state at the time of its writing.

A person’s self-worth is manifested in his attitude towards life and death. Tvardovsky’s heroes do not complain about life, they are not characterized by indifference to life, they do not lose the meaning of life under any circumstances. Therefore, the motif of love acquires special power in the poem. Here the poet’s desire to tell not about events, but through events about the life of the soul, is very strong.

Yes, friends, wife's love, -

If you didn't know, check it out -

War is stronger than war

And perhaps death.

These famous lines from “Vasily Terkin” become one of the leitmotifs of the poem “House by the Road”.

War breaks vital connections, a person strives to restore them. Trying to find out about her husband and hearing about another Sintsov, Anna feels a family connection with him and with all of humanity: “But somehow dear to her // And that namesake.”

The hero of "Road House" is not a hero, not a miracle man. He can doubt, grieve, retreat, be ashamed of weakness, be just a person. But he knows how to love to death, and to love to death.

And that love was strong with such a powerful force,

What one war could separate.

And separated.

The poems reflected what was in the soul of the poet himself: “...I think most of all about three things: about the war, about my work and about you and the children. And all this not separately, but together. Those. this constitutes my daily spiritual existence... And I don’t know how hard it would be for me, a hundred times harder than it sometimes is, if I didn’t have you and the children. Everything is so serious in the world, my dear, that I think that those people who preserve their tenderness and affection for each other now will be inseparable forever...” The heroes of his poem “House by the Road” have preserved these feelings for each other, which is why we believe that the heroes of the poem will meet and build a new house in every sense.

The poem is a reflection on life and death during the war, but not only on soldiers for whom war is service, who are ready to give their lives for their homeland. Civilians are drawn into the war, and, worst of all, the child is threatened with death. The struggle of life with death in the poem acquires such an intensity that was not seen either in “Vasily Terkin” or in the lyrics of this time. Here you can hear the echoes of the tragedy that happened in the life of the poet himself - the death of his little, beloved son Sasha. The existential situation in life turns out to be resolved in favor of death and remains an unhealed wound in the poet’s subconscious. And in the poem he defies death. For Tvardovsky, the tragedy of death lies not so much in physical dying, but in the loneliness of a person in the face of death. The death of his son was made even more terrible (if that is even possible) precisely because he found himself alone without parents at the time of death. Word one is repeated several times in Tvardovsky’s note about his son’s death: “They left the boy alone...”, “we were horrified that he was a small one in the hospital...”, “That’s it, son,” I said, and we hurried to car, and our boy was left alone” and the consonant word “abandoned”: “They looked at him again, how he was lying, a poor, offended, abandoned boy with a flower in his hands (he loved flowers very much - he especially loved to blow dandelions) and closed ". And this image of a flower in the hands of a dead boy goes into the poem “Road House” and becomes a sign of life that has conquered death:

And the eldest daughter in the house,

Who needs to babysit the little ones?

I found him a Fluffy Dandelion in Germany.

And the weak boy blew for a long time,

I breathed on that head...

In many of Tvardovsky’s works, loneliness becomes a symbol of death and determines the search for the meaning of life. He finds a way out in the community of people

dey. In the poem “House by the Road,” life wins precisely because the community of people, even in the most cruel conditions of captivity, helped a tiny child survive. Beginning the story about a child who was born in captivity, Tvardovsky repeats the words like a spell: “And he began to live while alive, a prison resident from birth.” The living and the dead exist in opposition from the very beginning:

You were born alive,

And there is insatiable evil in the world.

The living are in trouble, but the dead are not,

Death is protected.

In the monologue on behalf of the child, in 16 stanzas, words with the same root as the word “life” occur 9 times: life - live - live - alive - survive - survive - live - inhabitant - live. And not a single word with the same root as the word “death,” although death was incomparably closer than life.

In the poem, the life-death antinomy is revealed in another very striking motif - nature and death. For Tvardovsky, nature is an aesthetic and philosophical phenomenon, inseparable from human life. Nature for him - living creature in all its diversity. It comes into conflict with war and at the same time remains the only component of the world that remains constant. At the beginning of the poem, nature is called upon to convey the fullness of life, the peaceful life of the owner of the earth. This is revealed in the list of herb names:

The grass was kinder than the grass -

Peas, wild clover,

A thick panicle of wheatgrass and strawberry leaves.

And in the perception of a mower, when both sounds and smells give a feeling of happiness to a working person:

And you mowed her down, sniffling,

Groaning, sighing sweetly.

And I overheard myself

When the shovel rang.

A detail that is so important for Tvardovsky’s poetics and at first glance so insignificant, here becomes a symbol whose meaning will be revealed to the reader only after reading the entire poem.

This is the covenant and this is the sound,

And along the braid along the sting,

Washing away the little petals,

The dew ran like a stream.

The mowing is high, like a bed,

Lay down, fluffed up,

And the sleepy, wet bumblebee sang barely audibly in the mowing.

The poet reinforces the foreboding of the tragedy of war with pictures of nature. The more beautiful the picture of nature and life, the more terrible the war that destroys it.

Every detail of this description was supposed to testify to the beauty of life and the ugliness of death. The reader should have felt it, as the poet himself felt. A sign of trouble was the interruption of work, the owner “didn’t finish cutting”, and it was as if life itself had stopped. The cruelty of war is further enhanced by the image of bread destroyed by one’s own hands. Tvardovsky feels this as murder, because bread is the most important, the most sacred thing in a person’s life, what gives him life:

And you can’t count how many hands! -

Along that long ditch they rolled rye alive with damp, heavy clay.

Clay in Tvardovsky’s figurative system was a symbol of the severity of war and hostility. Let us remember in “Retribution”: “The fourth year! The fourth year of the war // He smears yellow Prussian clay on our elbows.” War violates both the harmony of nature itself and the harmony of its relationship with man. In the memoirs in which the poet talks about his impressions of a trip to the front in the first days of the war, the very contrast between life and death arises: on the one hand, refugees whose fate is unknown and most likely cruel, on the other, fields of blooming wheat: “ How I was struck by the smell in the open field, far from any gardens or beekeepers - a thick honey smell, gradually flavored with something like mint.” And although the poet does not say anything about the contradiction between nature and war, the conclusion suggests itself: only merging with nature, with the infinity and eternity of the natural world, when a person feels like a master, makes it possible to survive in any circumstances, gives him the right to immortality. And in this Tvardovsky is close to Leo Tolstoy. Tvardovsky’s heroes could exclaim just like Tolstoy’s hero: “And all this is mine. And it’s all in me, and it’s all me!” The optimism of the poem “Road House” grows out of the victory of man over death, who feels himself eternal precisely because he is part of eternity, the infinity of being, but only in harmony with nature, with love and much more.

The refrain of the poem “Mow, scythe, // Until the dew, // Down with the dew - // And we’re home” connects the past, present and future, creates a sense of the integrity of life, affirms the possibility of a happy future life. Nature for the heroine in captivity is at first hostile: “An alien sea behind the wall // A turning of stones.” The word “alien” seems to remove those captured from the outside world. The stones that are tossed by the sea symbolize the heaviness of the heroine’s thoughts and feelings. “Fierce wind at night” is the personification of the ferocity of the surrounding world. Just like in folklore, everything seems to be against the heroes. The situation is gradually changing, although the heroes cannot yet fully accept it. The landscape is similar to his native one, the poet lists the familiar features of nature, but all this is alien:

But even though there is earth, there is earth everywhere,

But somehow differently

Strangers smell of poplars

And rotten straw.

Forced exclusion from home, isolation from home, even loss of home, as in the case of Anna - all this was the subject of constant reflection by Tvardovsky, who left his home at a very young age. And it gave such depth philosophical sound house motif. The poet admitted more than once that he was not attracted to foreign travel, he was reluctant to change his apartment and dacha: the house and everything that is included in this concept was sacred to him. Therefore, in the poem, precisely in captivity and precisely at the moment of awakening of nature, reminiscent of her homeland, for the first time the heroine calls herself by name, as if waking up from a terrible dream, she wants to understand, realize who she is, where she is, thereby, as it were, to assert herself on the ground.

The stream gurgled in its own way in the unloved fields of others,

And the water in the concrete pipes seemed salty to her.

And in someone else's big yard

Under the tiled roof

The rooster seemed to be at dawn

He's loud-mouthed in an unusual way.

The images in this passage represent an internal contradiction with the world that Tvardovsky created before the war. In peaceful life they were symbols of life. Here the water is “salty” like tears, and even the rooster, which has always personified the homeland, happiness, warmth and comfort, here “bawls unusually.” And only the knowledge that liberation is approaching gives new sensations: nature now becomes a friend, the first sign of memories of peaceful pre-war life:

Early mowing time Beyond the distant limits Has come. They smelled like clover,

Chamomiles, white porridges.

And this memorable mixture of flowers from the time of the beloved was like news for the heart from the side of the beloved.

And these smells longing for that alien land, as if coming from afar -

From afar from the east.

It was the mowing that became such a first sign; it evoked in memory that other pre-war mowing, which was among the happy events summer day and which was so cruelly interrupted by the war. The motif of mowing has always had a special meaning in Russian literature. The heroes of Tolstoy, Bunin, Zaitsev were revealed in a new way, morally enriched by their involvement in peasant labor. In Tvardov's poem-

The sky's mowing becomes a symbol of life. Only mowing time brings hope for new life Andrei is finishing his new house just in time for mowing.

Mowing treats:

So that grief gets busy,

The soldier got up at dawn and drove the swath wider and wider -

For all four summers.

Mowing becomes a measure of time:

Following the scythe, the soldier shook his back with gray sweat.

And exactly the time in its own way,

He measured it with his own measure.

Bread is one of those enduring values, the inviolability of which is sacred to the poet. The beginning of the war, its unnaturalness, is marked by the fact that “they rolled the rye alive // With raw heavy clay // Live bread, alive grass // They rolled it themselves.” The repetition and the word “ourselves” only emphasize the horror of what is happening for the peasant, for the owner who is accustomed to taking care of nature, respecting his work and thanking the land for the harvest. Thus, the harmony of nature is combined with the harmony of the human spirit, and only then is the moral ideal to which everyone strives is achieved.

By leaving the poem unfinished, Tvardovsky thereby creates a feeling of the eternity of life.

Having won life from death, the poet philosophically comprehends the path of the Russian man in the bloodiest war of the twentieth century and affirms it human essence:

And carried with him his sadness,

Both pain and faith in happiness.

Mow, scythe,

While there is dew,

Down with the dew -

And we're home.

Thus, the end-to-end antinomy of life-death in the poem is revealed not only in the action itself, but also in images, symbols, and additional motives. And this internal duel sometimes turns out to be even brighter and stronger than external events, and the brighter and stronger is the victory of life over death.

LITERATURE

Tvardovsky A. “I went on my own attack...” Diary. Letters. 1941-1945. - M.: Vagri-

Panova E.P. The motive of the “prodigal son” and its transformation in Russian literature // World literature for children and about children. Issue eight. - M.: MPGU, 2003.

Tvardovsky A.T. Collection Op. in 6 volumes. - M.: Fiction, 1976-1983

Akatkin V.M. Alexander Tvardovsky and time. Service and confrontation. Articles. - Voronezh, 2006.

Burtin Yu.G. Three poems by Tvardovsky // Burtin Yu.G. Confession of a sixties man. - M.: Progress-tradition, 2003.

Tvardovskaya M.I. Kolodnya // Memories of A.T. Tvardovsky. - M., 1978.

ANTINOMY “LIFE - DEATH” AND IT’S INCARNATION IN ARTISTIC IMAGES IN A.T. TVARDOVSKY’S POEM “A HOUSE BY THE ROAD”

The Department of Russian language Medical faculty Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia Miklukho-Maklaya str. 6, Moscow, Russia, 117198

This research is devoted to the analysis of such philosophical problem of life and death in A.T. Tvar-dovsky’s poem “A House by the Road”. The article reveals such motives as house, road, family, father, mother, love, nature and child in the situation of death during The Great Patriotic War, incarnated in artistic images of the poem.

Alexander Tvardovsky

HOUSE BY THE ROAD

Lyrical chronicleI started the song in a difficult year,

When it's cold in winter

The war was at the gates

Capitals under siege.

But I was with you, soldier,

Always with you -

Before and since that winter in a row

In one wartime period.

I only lived by your fate

And he sang it to this day,

And I put this song aside

Interrupting halfway through.

And how could you not return?

From the war to his soldier wife,

So I couldn't

All this time

Return to that notebook.

But as you remembered during the war

About what is dear to the heart,

So the song, starting in me,

She lived, seethed, ached.

And I kept it inside me,

I read about the future

And the pain and joy of these lines

Hiding others between the lines.

I carried her and took her with me

From the walls of my native capital -

Following you

Following you -

All the way abroad.

From border to border -

At every new place

The soul waited with hope

Some kind of meeting, conduct...

And wherever you go

What kind of houses have thresholds,

I never forgot

About a house by the road,

About the house of sorrows, by you

Once abandoned.

And now on the way, in a foreign country

I came across a soldier's house.

That house without a roof, without a corner,

Warm in a residential way,

Your mistress took care

Thousands of miles from home.

She pulled somehow

Along the highway track -

With the smaller one, asleep in my arms,

And the whole family crowd.

The rivers boiled under the ice,

The streams churned up foam,

It was spring and your house was walking

Home from captivity.

He walked back to the Smolensk region,

Why was it so far away...

And every soldier's look

I felt warm at this meeting.

And how could you not wave

Hand: “Be alive!”

Don't turn around, don't breathe

About many things, service friend.

At least about the fact that not everything

Of those who lost their home,

On your frontline highway

They met him.

You yourself, walking in that country

With hope and anxiety,

I didn’t meet him in the war, -

He walked the other way.

But your house is assembled, it is obvious.

Build walls against it

Add a canopy and porch -

And it will be an excellent house.

I'm willing to put my hands to it -

And the garden, as before, at home

Looks through the windows.

Live and live

Ah, to live and live for the living!

And I would sing about that life,

About how it smells again

At a construction site with gold shavings,

Live pine resin.

How, after announcing the end of the war

And longevity to the world,

A starling refugee has arrived

To a new apartment.

How greedily the grass grows

Thick on the graves.

The grass is right

And life is alive

But I want to talk about this first,

What I can’t forget about.

So the memory of grief is great,

Dull memory of pain.

It won't stop until

He won’t speak out to his heart’s content.

And at the very noon of the celebration,

For the holiday of rebirth

She comes like a widow

A soldier who fell in battle.

Like a mother, like a son, day after day

I waited in vain since the war,

And forget about him again,

And don't mourn all the time

Not domineering.

May they forgive me

That again I'm before the deadline

I'll be back, comrades,

To that cruel memory.

At that very hour on Sunday afternoon,

On a festive occasion,

In the garden you mowed under the window

Grass with white dew.

The grass was kinder than the grass -

Peas, wild clover,

Dense panicle of wheatgrass

And strawberry leaves.

And you mowed her down, sniffling,

Groaning, sighing sweetly.

And I overheard myself

When the shovel rang:

Mow, scythe,

While there is dew,

Down with the dew -

And we're home.

This is the covenant and this is the sound,

And along the braid along the sting,

Washing away the little petals,

The dew ran like a stream.

The mowing is high, like a bed,

Lay down, fluffed up,

And a wet, sleepy bumblebee

While mowing he sang barely audibly.

And with a soft swing it’s hard

The scythe creaked in his hands.

And the sun burned

And things went on

And everything seemed to sing:

Mow, scythe,

While there is dew,

Down with the dew -

And we're home.

And the front garden under the window,

And the garden, and the onions on the ridges -

All this together was a home,

Housing, comfort, order.

Not the order and comfort

That, without trusting anyone,

They serve water to drink,

Holding onto the door latch.

And that order and comfort,

What to everyone with love

It's like they're serving a glass

To good health.

The washed floor shines in the house

Such neatness

What a joy for him

Step barefoot.

And it’s good to sit down at your table

In a close and dear circle,

And, while resting, eat your bread,

And it’s a wonderful day to praise.

That really is the day of better days,

When suddenly we suddenly -

The food tastes better

My wife is nicer

And the work is more fun.

Mow, scythe,

While there is dew,

Down with the dew -

And we're home.

Oct 26 2010

A.T. Tvardovsky began writing the poem “House by the Road” in 1942, returned to it again and finished it in 1946. This is a poem about fate peasant family, a small, modest part of the people, upon which all the misfortunes and sorrows fell. Having fought off his own, Andrei Sivtsov found himself behind enemy lines, near his own house, feeling tired from the hardships he had endured. All the more expensive is his decision to continue the path to the front, “to recognize the route not written by anyone in the stars.” Making this decision, Sivtsov feels “indebted” to his comrade who died on the way: And since he walked, but didn’t get there, So I have to get there. ... It would be good if he were alive, Otherwise he is a fallen warrior. Sivtsov’s misadventures were not at all uncommon at that time. The fate of his loved ones turned out to be the same common for many, many families 157: Anna and her children were taken to Germany, to a foreign land. And there is yet another “trouble on top of troubles” ahead: in captivity, in a convict camp, the Sivtsovs had a son, seemingly doomed to inevitable death.

Anna's mental conversation with her son belongs to the most heartfelt pages ever written by Tvardovsky. The maternal need to talk with someone who is still “mute and stupid”, the doubt about the ability to protect the child, and the passionate desire to survive for the sake of her son are conveyed here with deep sensitivity. And although this new human being is so destitute, her light is still so weak, there is so little hope of meeting her father, life emerges victorious from an unequal duel with death threatening it.

Returning home, Andrei Sivtsov knows nothing about the fate of his family. Finally, she presented another bitter paradox - it is not the wife and children who are waiting for the soldier to come home, but he is waiting for them. Tvardovsky is stingy with direct praise for the hero, once describing him as the type of “ascetic fighter who, year after year in a row, fulfilled to the end.” He does not embellish it at all, even in the most dramatic situations, for example, when leaving the encirclement: “thin, overgrown, as if covered with ash,” wiping his mustache with the “fringe of the sleeve” of his overcoat, frayed in his wanderings.

In the essay “In Native Places” (1946), telling how his fellow villager, like Andrei Sivtsov, built a house on the ashes, Tvardovsky wrote: “It seemed more and more natural to me to define the construction of this simple log cabin as a kind of . The feat of a simple worker, grain grower and family man who shed blood in the war for native land and now on her, ruined and despondent over the years of his absence, beginning to start life all over again..."

The poem leaves it to the readers themselves to draw a similar conclusion, limiting themselves to a laconic description of Andrei Sivtsov’s quiet feat: I stayed for a day or two. - Well, thank you for that. - 158 literature And with a sore leg he dragged himself to the old seliba. I took a smoke break, took off my overcoat, and marked it out with a shovel. If you wait for your wife and children to come home, then you need to build a hut.

It is unknown whether the house built by the hero will wait for its owner, whether it will be filled with children's voices. The fate of the Sivtsovs is the fate of millions, and the ending of these dramatic stories is not the same. In one of his articles, Tvardovsky noted that many best works Russian prose, “having arisen from living life... in their endings they strive, as it were, to close with the same reality, leaving the reader wide scope for mental continuation of them, for further thinking, “further research” of the human destinies, ideas and questions raised in them.”

Need a cheat sheet? Then save - "The poem "House by the Road" is a story about the fate of a peasant family. Literary essays!Portraying war through fate common man will also be characteristic of A. Tvardovsky’s poem “House by the Road” (1946). But the emphasis in this work will be on something else. “Vasily Terkin” is an epic poem, it shows a man fighting, a man at the front. In “Road House,” an event that is epic in nature is revealed through lyrical techniques. House and road, family and war, man and history - the work of A. Tvardovsky is built at the intersection of these motifs. It contained the same bitter, tragic melody as in the poem by the senior fellow countryman, the poet Mikhail Isakovsky, “Enemies burned their home.” The time when these works were created turned out to be not at all favorable for thinking about the cost of our victory, about the grief of the liberating soldiers who returned home and found only “a hillock overgrown with grass.” It was the second half of the 40s, the period of party resolutions on the magazines “Zvezda” and “Leningrad”, the time of the next “tightening” of the ideological “nuts”, tightening of censorship. Like Isakovsky’s poem, Tvardovsky’s poem “House by the Road”, and then his notes “Motherland and Foreign Land” aroused criticism in the press for pessimism and “decadent moods”, which, according to official propaganda, should not have been characteristic of the victors.

In the poem “Road House” there really is no heroic pathos, if by such we mean posterity and the romantically elevated tonality of the depiction of war. But there is true, quiet heroism here. The heroism of the peasants, who were forced to interrupt their peaceful labor and, just as naturally as they plowed and mowed the whole world, the whole world went to fight the enemy (initial scenes of the poem). The heroism of women who remained in the rear with the elderly and children and did not interrupt their work. The heroism of those who for many years were considered traitors, who were driven into captivity by the Nazis, but did not give up, did not lose heart, just as Anna Sivtsova was able to survive. The heroism of soldier Andrei Sivtsov, who returned from the war as a winner and found the strength to start life anew.

Andrei Sivtsov began life the way a Russian person always began it - with the construction of a hut that was burned by the war... The real truth lies in the open ending of the work, which the author did not end with a happy ending. Here only a melody of hope sounds, as in the line that became the leitmotif of the poem: “Mow, scythe, While the dew is on”... A child born of a woman and a house that a man builds is the personification of hope for the continuation of life, tragically disfigured, but not destroyed by war.

War - there is no crueler word.

War - there is no sadder word.

War - there is no holier word In the melancholy and glory of these years.

And on our lips there cannot be anything else.

These lines were written by A. Tvardovsky in 1944, when in the fire of battle it was still “not the time to remember.” But “on the day when the war ended” “and, covered with haze, it goes into the distance, the shore filled with comrades,” the time came for memory, summing up, thinking about the fallen and the living. The intonations of a requiem sounded in the poetry of A. Tvardovsky. From now on, the theme of the war, combined with a sense of guilt and moral duty to the dead (“I am yours, friends, and I am in your debt”), became a “cruel memory.” One of the first poems that opens this topic in the work of A. Tvardovsky and in post-war literature in general, written from the perspective of a fallen warrior:

I was killed near Rzhev,

In a nameless swamp

In the fifth company, on the left,

During a brutal attack.

The abrupt, almost protocol lines that open the poem emphasize the hopelessness of death.

The author’s thought moves from the particular, concrete plane to the generalized philosophical one. The soldier is emphatically nameless, he is one of the millions that lay in the ground without graves, became part of it, passed into the lives of those who survived, who were born later (“I am where the blind roots are,” “I am where the cock’s crow is,” “I – where are your cars? This poem is an appeal to “faithful comrades”, “brothers” with a single testament - to live with dignity.

The motif of the unity of the living and the dead, “mutual connection,” kinship, responsibility “for everything in the world” will become the leitmotif of A. Tvardovsky’s post-war work.

We stayed there, and it’s not about the same thing,

That I could, but failed to save them, -

This is not about that, but still, still, still...

The motif of “cruel memory” will become widespread not only in A. Tvardovsky’s works about the war. Piercingly, at the limit of sincerity, it will sound in the poet’s reflections “about time and about himself,” about his generation, about his own destiny.

I lived, I was - for everything in the world

I answer with my head.

These words of A. Tvardovsky determine the pathos of his post-war work, becoming not only a symbol of the inextricable connection of a person with the fate of the country, with the century, but also expressing, as Pushkin wrote, “a person’s independence is the guarantee of his greatness.”

Searched here:

- house by the road summary

- Tvardovsky house by the road summary

- house by the road Tvardovsky summary