What is the title at the end of the year? Terms and procedure for assigning regular military ranks

The offensive of the Russian army, which began on June 4, 1916, was first declared its greatest success, then - its greatest failure. What was the Brusilov breakthrough really?

On May 22, 1916 (hereinafter all dates are in the old style) the Southwestern Front of the Russian army went on an offensive, which was recognized as brilliant for another 80 years. And since the 1990s, it began to be called an “attack on self-destruction.” However, a detailed acquaintance with the latest version shows that it is just as far from the truth as the first.

Story Brusilovsky breakthrough, like Russia as a whole, was constantly “mutating”. The press and popular prints of 1916 described the offensive as a great achievement of the imperial army, and painted its opponents as klutzes. After the revolution, Brusilov’s memoirs were published, slightly diluting the former official optimism.

According to Brusilov, the offensive showed that the war could not be won this way. After all, Headquarters was unable to take advantage of his successes, which made the breakthrough, although significant, but without strategic consequences. Under Stalin (according to the fashion of that time), failure to use the Brusilov breakthrough was seen as “treason.”

In the 1990s, the process of restructuring the past began with increasing acceleration. Employee of the Russian State Military Historical Archive Sergei Nelipovich first analysis of losses Southwestern Front Brusilov according to archival data. He discovered that the military leader's memoirs underestimated them several times. A search in foreign archives showed that the enemy’s losses were several times less than Brusilov stated.

The logical conclusion of the historian of the new formation was: the Brusilov impulse is a “war of self-destruction.” The historian believed that the military leader should have been removed from office for such “success”. Nelipovich noted that after the first success, Brusilov was given guards transferred from the capital. She suffered huge losses, so in St. Petersburg itself she was replaced by wartime conscripts. They were extremely unwilling to go to the front and therefore played a decisive role in the tragic events of February 1917 for Russia. Nelipovich’s logic is simple: without Brusilov’s breakthrough there would have been no February, and therefore no decomposition and subsequent fall of the state.

As often happens, the “conversion” of Brusilov from a hero to a villain led to a strong decrease in the interest of the masses in this topic. This is how it should be: when historians change the signs of the heroes of their stories, the credibility of these stories cannot help but fall.

Let's try to present a picture of what happened taking into account archival data, but, unlike S.G. Nelipovich, before evaluating them, let us compare them with similar events of the first half of the 20th century. Then it will become crystal clear to us why, given the correct archival data, he came to completely wrong conclusions.

The breakthrough itself

So, the facts: the Southwestern Front a hundred years ago, in May 1916, received the task of a distracting demonstrative attack on Lutsk. Goal: to pin down enemy forces and distract them from the main offensive of 1916 on the stronger Western Front (north of Brusilov). Brusilov had to take diversionary actions first. Headquarters urged him on, because the Austro-Hungarians had just begun to vigorously smash Italy.

There were 666 thousand people in the combat formations of the Southwestern Front, 223 thousand in the armed reserve (outside combat formations) and 115 thousand in the unarmed reserve. The Austro-German forces had 622 thousand in combat formations and 56 thousand in reserve.

The ratio of manpower in favor of the Russians was only 1.07, as in Brusilov’s memoirs, where he talks about almost equal forces. However, with substitutes, the figure increased to 1.48 - the same as Nelipovich.

But in terms of artillery, the enemy had an advantage - 3,488 guns and mortars versus 2,017 for the Russians. Nelipovich, without citing specific sources, points to the Austrians' lack of shells. However, this point of view is rather doubtful. To stop the enemy's growing chains, the defenders need fewer shells than the attackers. After all, during the First World War they had to conduct artillery bombardment for many hours on defenders hidden in trenches.

The close to equal balance of forces meant that Brusilov’s offensive, according to the standards of the First World War, could not be successful. At that time it was possible to advance without an advantage only in the colonies where there was no continuous front line. The fact is that since the end of 1914, for the first time in world history, a single multilayer trench defense system arose in the European theaters of war. In dugouts protected by meter-long ramparts, the soldiers waited out the enemy’s artillery barrage. When it subsided (so as not to hit their advancing chains), the defenders came out of cover and occupied the trench. Taking advantage of the many-hour warning in the form of a cannonade, reserves were brought up from the rear.

An attacker in an open field came under heavy rifle and machine gun fire and died. Or he captured the first trench with huge losses, after which he fought out of there with counterattacks. And the cycle repeated. Verdun in the West and the Naroch massacre in the East in the same 1916 once again showed that there are no exceptions to this pattern.

How to achieve surprise where it is impossible?

Brusilov did not like this scenario: not everyone wants to be a whipping boy. He planned a small revolution in military affairs. In order to prevent the enemy from finding out the offensive area in advance and pulling reserves there, the Russian military leader decided to deliver the main blow in several places at once - one or two in the zone of each army. The General Staff, to put it mildly, was not delighted and talked tediously about the dispersal of forces. Brusilov pointed out that the enemy would either scatter his forces too, or - if he didn’t scatter them - would allow his defenses to be broken through at least somewhere.

Before the offensive, Russian units opened trenches closer to the enemy (standard procedure at that time), but in many areas at once. The Austrians had never encountered anything like this before, so they believed that we were talking about distracting actions that should not be responded to by deploying reserves.

To prevent the Russian artillery barrage from telling the enemy when they would be hit, gunfire continued for 30 hours on the morning of May 22. Therefore, on the morning of May 23, the enemy was taken by surprise. The soldiers did not have time to return from the dugouts along the trenches and “were to put down their weapons and surrender, because as soon as even one grenadier with a bomb in his hands stood at the exit, there was no longer any salvation... It is extremely difficult to get out of the shelters in a timely manner and guess the time impossible".

By noon on May 24, the attacks of the Southwestern Front brought 41,000 prisoners - in half a day. The next time prisoners surrendered to the Russian army at such a rate was in 1943 in Stalingrad. And then after the surrender of Paulus.

Without capitulation, just like in 1916 in Galicia, such successes came to us only in 1944. There was no miracle in Brusilov’s actions: the Austro-German troops were ready for freestyle fighting in the style of the First World War, but were faced with boxing, which they saw for the first time in their lives. Just like Brusilov - in different places, with a well-thought-out system of disinformation to achieve surprise - the Soviet infantry of World War II went to break through the front.

Horse stuck in a swamp

The enemy front was broken through in several areas at once. At first glance, this promised enormous success. Russian troops had tens of thousands of quality cavalrymen. It was not for nothing that the then non-commissioned cavalrymen of the Southwestern Front - Zhukov, Budyonny and Gorbatov - assessed it as excellent. Brusilov's plan involved the use of cavalry to develop a breakthrough. However, this did not happen, which is why the major tactical success never turned into a strategic one.

The main reason for this was, of course, errors in cavalry management. Five divisions of the 4th Cavalry Corps were concentrated on the right flank of the front opposite Kovel. But here the front was held by German units, which were sharply superior in quality to the Austrian ones. In addition, the outskirts of Kovel, already wooded, at the end of May of that year had not yet dried out from the mud and were rather wooded and swampy. A breakthrough here was never achieved, the enemy was only driven back.

To the south, near Lutsk, the area was more open, and the Austrians who were there were not equal opponents to the Russians. They were subjected to a devastating blow. By May 25, 40,000 prisoners had been taken here alone. According to various sources, the 10th Austrian Corps lost, due to a disruption in the work of its headquarters, 60–80 percent of its strength. This was an absolute breakthrough.

But the commander of the Russian 8th Army, General Kaledin, did not dare to introduce his only 12th Army into the breakthrough. cavalry division. Its commander, Mannerheim, later became the head Finnish army in the war with the USSR, he was a good commander, but too disciplined. Despite understanding Kaledin's mistake, he only sent him a series of requests. Having been refused nomination, he obeyed the order. Of course, without even using his only cavalry division, Kaledin did not demand the transfer of the cavalry that was inactive near Kovel.

"All Quiet on the Western Front"

At the end of May, the Brusilov breakthrough - for the first time in that positional war - provided a chance for major strategic success. But the mistakes of Brusilov (cavalry against Kovel) and Kaledin (failure to introduce cavalry into the breakthrough) nullified the chances of success, and then the meat grinder typical of the First World War began. In the first weeks of the battle, the Austrians lost a quarter of a million prisoners. Because of this, Germany reluctantly began to collect divisions from France and Germany itself. By the beginning of July, with difficulty, they managed to stop the Russians. It also helped the Germans that the “main blow” of Evert’s Western Front was in one sector - which is why the Germans easily foresaw it and thwarted it.

Headquarters, seeing Brusilov’s success and the impressive defeat in the direction of the “main attack” of the Western Front, transferred all reserves to the Southwestern Front. They arrived “on time”: the Germans brought up troops and, during a three-week pause, created a new line of defense. Despite this, the decision was made to “build on the success”, which, frankly speaking, was already in the past by that point.

To cope with the new methods of the Russian offensive, the Germans began to leave only machine gunners in fortified nests in the first trench, and placed the main forces in the second and sometimes third line of trenches. The first turned into a false firing position. Since the Russian artillerymen could not determine where the bulk of the enemy infantry was located, most of the shells fell into empty trenches. It was possible to fight this, but such countermeasures were perfected only by the Second World War.

breakthrough,” although this word in the name of the operation traditionally applies to this period. Now the troops slowly gnawed through one trench after another, suffering more losses than the enemy.

The situation could have been changed by regrouping the forces so that they were not concentrated in the Lutsk and Kovel directions. The enemy was no fool, and after a month of fighting he clearly realized that the main “kulaks” of the Russians were located here. It was unwise to continue hitting the same point.

However, those of us who have encountered generals in life understand perfectly well that the decisions they make do not always come from reflection. Often they simply carry out the order “strike with all forces... concentrated in the N-th direction,” and most importantly - as soon as possible. A serious maneuver by force excludes “as soon as possible,” which is why no one undertook such a maneuver.

Perhaps, if the General Staff, headed by Alekseev, had not given specific instructions on where to strike, Brusilov would have had freedom of maneuver. But in real life, Alekseev did not give it to the front commander. The offensive became Verdun of the East. A battle where it is difficult to say who is exhausting whom and what all this is all about. By September, due to the shortage of shells among the attackers (they almost always spend more), the Brusilov breakthrough gradually died out.

Success or failure?

In Brusilov's memoirs, Russian losses are half a million, of which 100,000 were killed and captured. Enemy losses - 2 million people. Like the research of S.G. Nelipovich, who is conscientious in terms of working with archives, does not confirm these figures in his documents.

war of self-destruction." He is not the first in this. Although the researcher does not indicate this fact In his works, the emigrant historian Kersnovsky was the first to speak about the meaninglessness of the late (later July) phase of the offensive.

In the 90s, Nelipovich made comments on the first edition of Kersnovsky in Russia, where he encountered the word “self-destruction” in relation to the Brusilov breakthrough. From there he gleaned information (later clarified by him in the archives) that the losses in Brusilov’s memoirs were false. It is not difficult for both researchers to notice the obvious similarities. To Nelipovich’s credit, he sometimes still “blindly” puts references to Kersnovsky in the bibliography. But, to his “disgrace,” he does not indicate that it was Kersnovsky who was the first to talk about “self-destruction” on the Southwestern Front since July 1916.

However, Nelipovich also adds something that his predecessor does not have. He believes that the Brusilov breakthrough is undeservedly called such. The idea of more than one strike at the front was proposed to Brusilov by Alekseev. Moreover, Nelipovich considers the June transfer of reserves to Brusilov as the reason for the failure of the offensive of the neighboring Western Front in the summer of 1916.

Nelipovich is wrong here. Let's start with Alekseev's advice: he gave it to all Russian front commanders. It’s just that everyone else hit with one “fist”, which is why they weren’t able to break through anything at all. Brusilov's front in May-June was the weakest of the three Russian fronts - but he struck in several places and achieved several breakthroughs.

"Self-destruction" that never happened

What about "self-destruction"? Nelipovich’s figures easily refute this assessment: the enemy lost 460 thousand killed and captured after May 22. This is 30 percent more than the irretrievable losses of the Southwestern Front. For the First World War in Europe, the figure is phenomenal. At that time, the attackers always lost more, especially irrevocably. The best loss ratio.

We must be glad that sending reserves to Brusilov prevented his northern neighbors from attacking. To achieve its results of 0.46 million captured and killed by the enemy, front commanders Kuropatkin and Evert would have to lose more personnel than they had. The losses that the guard suffered at Brusilov would be a trifle compared to the carnage that Evert carried out on the Western Front or Kuropatkin on the North-Western.

In general, reasoning in the style of “war of self-destruction” in relation to Russia in the First World War is extremely doubtful. By the end of the war, the Empire had mobilized a much smaller part of the population than its Entente allies.

With regard to the Brusilov breakthrough, for all its mistakes, the word “self-destruction” is doubly dubious. Let us remind you: Brusilov took prisoners in less than five months than the USSR managed to take in 1941–1942. And several times more than, for example, what was taken at Stalingrad! This is despite the fact that at Stalingrad the Red Army irrevocably lost almost twice as much as Brusilov did in 1916.

If the Brusilov breakthrough is a war of self-destruction, then other contemporary offensives of the First World War are pure suicide. Compare Brusilov's "self-destruction" with the Great Patriotic War, in which irrecoverable losses Soviet army were several times higher than that of the enemy, is generally impossible.

Let's summarize: everything is learned by comparison. Indeed, having achieved a breakthrough, Brusilov in May 1916 was unable to develop it into a strategic success. But who could do something like that in the First World War? He carried out the best Allied operation of 1916. And - in terms of losses - the best major operation that the Russians armed forces managed to carry out against a serious opponent. For the First World War, the result was more than positive.

Undoubtedly, the battle that began a hundred years ago, for all its meaninglessness after July 1916, was one of the best offensives of the First World War.

Almost 100 years ago, in early August, one of the most famous land operations of the First World War under the authorship of Russian General Alexei Brusilov ended. The general's troops broke through the Austro-German front thanks to an original tactical innovation: for the first time in the history of wars, the commander concentrated his forces and delivered powerful blows to the enemy in several directions at once. However, the offensive, which offered a chance to quickly end the war, was not brought to its logical conclusion.

In May 1916, hostilities in Europe became protracted. In military affairs, this is called the plausible term “positional warfare,” but in fact it is an endless sitting in the trenches with unsuccessful attempts to go on a decisive offensive, and each attempt results in huge casualties. Such, for example, are the famous battles on the Marne River in the fall of 1914 and on the Somme in the winter and spring of 1916, which did not produce tangible results (if you do not take hundreds of thousands of dead and wounded on all sides as a “result”) neither to Russia’s allies in the Entente bloc - England and France, nor their opponents - Germany and Austria-Hungary.

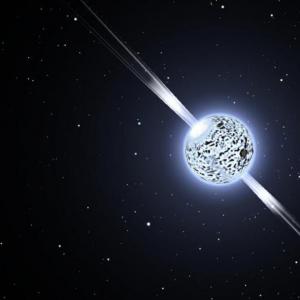

General A. A. Brusilov (life: 1853-1926).

The Russian commander, Adjutant General Alexey Alekseevich Brusilov, studied the experience of these battles and came to interesting conclusions. The main mistake of both the Germans and the Allies was that they acted according to outdated tactics, known since the Napoleonic Wars. It was assumed that the enemy front needed to be broken through with one powerful blow in a narrow area (as an example from the biography of Napoleon Bonaparte, let us recall Borodino and the persistent attempts of the French to crush Kutuzov’s left flank - Bagration’s flushes). Brusilov believed that at the beginning of the 20th century, with the development of the fortification system, the advent of mechanized equipment and aviation, holding the attacked area and quickly delivering reinforcements to it was no longer an insurmountable task. The general developed new concept offensive: several strong blows in different directions.

Initially, the offensive of Russian troops in 1916 was scheduled for mid-summer, and the Southwestern Front, commanded by Brusilov (he was opposed mainly by the troops of Austria-Hungary), was assigned a secondary role. Main goal was to contain Germany in the eastern theater of operations, so that almost all reserves were at their disposal on the Northern and Western fronts. But Brusilov managed to defend his ideas before Headquarters, headed by Emperor Nicholas II. This was partly due to the change operational situation: In early to mid-May, the troops of Italy - another ally of England, France and Russia - suffered a major defeat from the Austrians at Trentino. To prevent the transfer of additional Austrian and German divisions to the west and the final defeat of the Italians, the Allies asked Russia to launch an offensive ahead of schedule. Now Brusilov’s Southwestern Front was supposed to participate in it.

"Brusilovsky" infantry on the Southwestern Front in 1916.

The general had four Russian armies at his disposal - the 7th, 8th, 9th and 11th. The front troops at the start of the operation numbered more than 630 thousand people (of which 60 thousand were cavalry), 1,770 light guns and 168 heavy guns. In manpower and light artillery, the Russians were slightly - about 1.3 times - superior to the Austrian and German armies opposing them. But in heavy artillery the enemy had an overwhelming, more than threefold advantage. This balance of power gave the Austro-German bloc an excellent opportunity for defensive battles. Brusilov, however, even managed to take advantage of this fact: he correctly calculated that in the event of a successful Russian breakthrough, it would be extremely difficult for the “heavy” enemy troops to organize quick counterattacks.

Russian gun crew from the First World War.

The simultaneous offensive of four Russian armies, which received the name “Brusilovsky breakthrough” in history, began on May 22 (June 4 in modern style) along a front with a total length of about 500 km. Brusilov - and this was also a tactical innovation - paid great attention to artillery preparation: for almost a day, Russian artillery continuously hit the Austro-Hungarian and German positions. The southernmost of the Russian armies, the ninth, was the first to go on the offensive, inflicting a crushing blow on the Austrians in the direction of the city of Chernivtsi. The army commander, General A. Krylov, also used an original initiative: his artillery batteries constantly misled the enemy, transferring fire from one area to another. The subsequent infantry attack was a complete success: the Austrians did not understand until the very end which side to expect it from.

A day later, the Russian 8th Army went on the offensive, striking Lutsk. The deliberate delay was explained very simply: Brusilov understood that the Germans and Austrians, in accordance with the prevailing concepts of tactics and strategy, would decide that Krylov’s 9th Army was delivering the main blow, and would transfer reserves there, weakening the front line in other sectors. The general's calculations were brilliantly justified. If the pace of advance of the 9th Army slowed down slightly due to counterattacks, the 8th Army (with the support of the Seventh, which delivered an auxiliary attack from the left flank) literally swept away the weakened enemy defenses. Already on May 25, Brusilov’s troops took Lutsk, and in general, in the first days they advanced to a depth of 35 km. The 11th Army also went on the offensive in the Ternopil and Kremenets area, but here the successes of the Russian troops were somewhat more modest.

Brusilovsky breakthrough. Stages of the operation and directions of the main attacks. The dates in the title and legend of the map are given in the new style.

General Brusilov designated the city of Kovel, northwest of Lutsk, as the main goal of his breakthrough. The calculation was that a week later the troops of the Russian Western Front would begin to attack, and the southern German divisions in this sector would find themselves in huge “pincers”. Alas, the plan never came to fruition. The commander of the Western Front, General A. Evert, delayed the offensive, citing rainy weather and the fact that his troops did not have time to complete their concentration. He was supported by the Chief of Staff of the Headquarters M. Alekseev, a long-time ill-wisher of Brusilov. Meanwhile, the Germans, as expected, transferred additional reserves to the Lutsk area, and Brusilov was forced to temporarily stop the attacks. By June 12 (25), Russian troops moved to the defense of the occupied territories. Subsequently, in his memoirs, Alexey Alekseevich wrote with bitterness about the inaction of the Western and Northern fronts and, perhaps, these accusations have grounds - after all, both fronts, unlike Brusilov, received reserves for a decisive attack!

The offensive of Brusilov's army. Modern illustration, stylized as a black and white photo.

As a result, the main actions in the summer of 1916 took place exclusively on the Southwestern Front. At the end of June and beginning of July, Brusilov’s troops again tried to advance: this time fighting deployed on the northern sector of the front, in the area of the Stokhod River, a tributary of the Pripyat. Apparently, the general had not yet lost hope for active support from the Western Front - the strike through Stokhod almost repeated the idea of the failed “Kovel pincers”. Brusilov's troops again broke through the enemy's defenses, but were unable to cross the water barrier on the move. The general made his last attempt at the end of July and beginning of August 1916, but the Western Front did not help the Russians, and the Germans and Austrians, having thrown fresh units into battle, offered fierce resistance. The Brusilov breakthrough has fizzled out.

And this is a documentary photograph of the consequences of the breakthrough. The photo shows apparently destroyed Austro-Hungarian positions.

The results of the offensive can be assessed in different ways. From a tactical point of view, it was undoubtedly successful: the Austro-German troops lost up to one and a half million people killed, wounded and prisoners (versus 500 thousand for the Russians), Russian Empire occupied a territory with a total area of 25 thousand sq. km. A by-product was that soon after Brusilov’s success, Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente, significantly complicating the situation for Germany and Austria-Hungary.

On the other hand, Russia did not take advantage of the opportunity to quickly end the hostilities in its favor. In addition, Russian troops received an additional 400 km of front line, which needed to be controlled and protected. After the Brusilov breakthrough, Russia again got involved in a war of attrition, in which it had no chance. The war was rapidly losing popularity among the people, mass protests intensified, and the morale of the army was undermined. The very next year, 1917, this led to devastating consequences within the country.

Ironic image German soldiers, surrendering to Brusilov. The author, oddly enough, is also a German - a contemporary of the events, the artist Hermann-Paul.

Interesting fact. German strategists learned “Brusilov’s lesson” very well. Confirmation of this is the military operations of Germany a little over 20 years later, at the beginning of the Second World War. Both the “Manstein plan” to defeat France and the infamous “Barbarossa” plan to attack the USSR were actually built on the ideas of the Russian general: concentration of forces and breakthrough of the front in several directions at the same time.

The plan of Hitler's general (future field marshal) Erich von Manstein to defeat France. Compare with the map of the Brusilov breakthrough: doesn’t it look similar?

The Brusilov breakthrough, in short, was one of largest operations carried out on the Eastern Front of the First World War. Unlike other battles and engagements, it was not named after geographical object, where it took place, and by the name of the general under whose command it was carried out.

Preparing for the offensive

The offensive in the summer of 1916 was an integral part general plan allies. It was originally planned for mid-June, while the Anglo-French troops were supposed to launch the Somme offensive two weeks later.

However, events unfolded a little differently than planned.

On April 1, during the military council, it was determined that everything was ready for the offensive operation. In addition, at that time the Russian army had a numerical superiority over the enemy in all three directions of combat operations.

An important role in the decision to postpone the offensive was played by the plight in which Russia’s allies found themselves. On the Western Front at this time, the “Verdun meat grinder” continued - the battle for Verdun, in which the Franco-British troops suffered heavy losses, and on the Italian front the Austro-Hungarians pushed back the Italians. To give the Allies at least a little respite, it was necessary to draw the attention of the German-Austrian armies to the east.

Also, the commanders and commander-in-chief feared that if they did not prevent the enemy’s actions and did not help the allies, then, having defeated them, the German army in full force would move to the borders of Russia.

At this time, the Central Powers did not even think about preparing for an offensive, but they created an almost impenetrable defensive line. The defense was especially strong on that section of the front where General A. Bursilov was supposed to carry out the offensive operation.

Defense Breakthrough

The offensive of the Russian army became for its opponents a complete surprise. The operation began in the dead of night on May 22 with many hours of artillery preparation, as a result of which the first line of enemy defense was practically destroyed and his artillery was partially neutralized.

The subsequent breakthrough was carried out in several small areas at once, which subsequently expanded and deepened

By the middle of the day on May 24, Russian troops managed to capture almost a thousand Austrian officers and more than 40 thousand ordinary soldiers and capture more than 300 units of various guns.

The ongoing offensive forced the Central Powers to hastily transfer additional forces there.

Literally every step was difficult for the Russian army. Bloody battles and numerous losses accompanied the capture of each settlement, each strategically important object. However, only by August the offensive began to weaken due to increased enemy resistance and fatigue of the soldiers.

Results

The result of the Brusilov breakthrough of the First World War, in short, was the advance of the front line deeper into enemy territory by an average of 100 km. Troops under the command of A. Brusilov occupied most of Volyn, Bukovina and Galicia. At the same time, Russian troops inflicted huge losses on the Austro-Hungarian army, from which it was no longer able to recover.

Also, the actions of the Russian army, which led to the transfer of several German military units from the Western and Italian fronts, allowed the Entente countries to achieve some success in those areas as well.

In addition, it was this operation that became the impetus for the decision to enter Romania into the war on the side of the Entente.

Brusilovsky breakthrough

Brusilovsky breakthrough- offensive operation of the Southwestern Front of the Russian army under the command of General A. A. Brusilov during the First World War, carried out on May 21 (June 3) - August 9 (22), 1916, during which a serious defeat was inflicted on the Austro-Hungarian army and Galicia and Bukovina are occupied.

Planning and preparation of the operation

The summer offensive of the Russian army was part of the Entente's overall strategic plan for 1916, which provided for the interaction of the allied armies in various theaters of war. As part of this plan, Anglo-French troops were preparing an operation on the Somme. In accordance with the decision of the conference of the Entente powers in Chantilly (March 1916), the start of the offensive on the French front was scheduled for July 1, and on the Russian front - for June 15, 1916.

The directive of the Russian Headquarters of the High Command of April 11 (24), 1916 ordered a Russian offensive on all three fronts (Northern, Western and Southwestern). The balance of forces, according to Headquarters, was in favor of the Russians. At the end of March, the Northern and Western Fronts had 1,220 thousand bayonets and sabers versus 620 thousand for the Germans, and the Southwestern Front had 512 thousand versus 441 thousand for the Austrians. The double superiority in forces north of Polesie also dictated the direction of the main attack. It was to be carried out by troops of the Western Front, and auxiliary attacks by the Northern and Southwestern Fronts. To increase the superiority in forces, in April-May the units were replenished to full strength.

Russian infantry on the march |

Headquarters feared that the armies of the Central Powers would go on the offensive if the French were defeated at Verdun and, wanting to seize the initiative, instructed the front commanders to be prepared for an offensive earlier than planned. The Stavka directive did not reveal the purpose of the upcoming operation, did not provide for the depth of the operation, and did not indicate what the fronts were supposed to achieve in the offensive. It was believed that after the first line of enemy defense had been broken through, a new operation was being prepared to overcome the second line. This was reflected in the planning of the operation by the fronts. Thus, the command of the Southwestern Front did not determine the actions of its armies in the development of the breakthrough and further goals.

Contrary to the assumptions of the Headquarters, the Central Powers did not plan large offensive operations on the Russian front in the summer of 1916. At the same time, the Austrian command did not consider it possible for the Russian army to launch a successful offensive south of Polesie without its significant reinforcement.

By the summer of 1916, signs of war fatigue among the soldiers appeared in the Russian army, but in the Austro-Hungarian army the reluctance to fight was much stronger, and in general the combat effectiveness of the Russian army was higher than the Austrian one.

On May 2 (15), Austrian troops went on the offensive on the Italian front in the Trentino region and defeated the Italians. In this regard, Italy turned to Russia with a request to help with the offensive of the armies of the Southwestern Front, which was opposed mainly by the Austrians. On May 18 (31), the Headquarters, by its directive, scheduled the offensive of the Southwestern Front for May 22 (June 4), and the Western Front for May 28-29 (June 10-11). The main attack was still assigned to the Western Front (commanded by General A.E. Evert).

In preparation for the operation, the commander of the Southwestern Front, General A. A. Brusilov, decided to make one breakthrough at the front of each of his four armies. Although this scattered the Russian forces, the enemy also lost the opportunity to timely transfer reserves to the direction of the main attack. In accordance with the general plan of the Headquarters, a strong right-flank 8th Army launched the main attack on Lutsk to facilitate the planned main attack of the Western Front. Army commanders were given freedom to choose breakthrough sites. In the directions of the armies' attacks, superiority over the enemy was created in manpower (2-2.5 times) and in artillery (1.5-1.7 times). The offensive was preceded by thorough reconnaissance, training of troops, and the equipment of engineering bridgeheads, which brought the Russian positions closer to the Austrian ones.

Progress of the operation

The artillery preparation lasted from 3 a.m. on May 21 (June 3) to 9 a.m. on May 23 (June 5) and led to severe destruction of the first line of defense and partial neutralization of enemy artillery. The Russian 8th, 11th, 7th and 9th armies (over 633,000 people and 1,938 guns) that then went on the offensive broke through the positional defenses of the Austro-Hungarian front, commanded by Archduke Frederick. The breakthrough was carried out in 13 areas at once, followed by development towards the flanks and in depth.

The greatest success at the first stage was achieved by the 8th Army (commanded by General A. M. Kaledin), which, having broken through the front, occupied Lutsk on May 25 (June 7), and by June 2 (15) defeated the 4th Austro-Hungarian Army of the Archduke Joseph Ferdinand and advanced 65 km.

The 11th and 7th armies broke through the front, but the offensive was stopped by enemy counterattacks. The 9th Army (commanded by General P. A. Lechitsky) broke through the front of the 7th Austro-Hungarian Army and occupied Chernivtsi on June 5 (18).

The threat of an attack by the 8th Army on Kovel forced the Central Powers to transfer two German divisions from the Western European theater, two Austrian divisions from the Italian front, and a large number of units from other sectors of the Eastern Front to this direction. However, the counterattack of the Austro-German troops against the 8th Army, launched on June 3 (16), was not successful.

At the same time, the Western Front postponed the delivery of the main attack prescribed to it by Headquarters. With the consent of the Chief of the General Staff, General M.V. Alekseev, General Evert postponed the date of the offensive of the Western Front until June 4 (17). A private attack by the 1st Grenadier Corps on a wide section of the front on June 2 (15) was unsuccessful, and Evert began a new regrouping of forces, which is why the Western Front offensive was postponed to the beginning of July. Applying to the changing timing of the offensive of the Western Front, Brusilov gave the 8th Army more and more new directives - now of an offensive, now of a defensive nature, to develop an attack now on Kovel, now on Lvov.

By June 12 (25), relative calm had established on the Southwestern Front. On June 24, artillery preparation of the Anglo-French armies on the Somme began, which lasted 7 days, and on July 1, the Allies went on the offensive. The operation on the Somme required Germany to increase the number of its divisions in this direction from 8 to 30 in July alone.

The Russian Western Front finally went on the offensive on June 20 (July 3), and the Southwestern Front resumed its offensive on June 22 (July 5). Dealing the main blow to the large railway junction of Kovel, the 8th Army reached the line of the river. Stokhod, but in the absence of reserves was forced to stop the offensive for two weeks.

|

The attack on Baranovichi by the strike group of the Western Front, launched on June 20-25 (July 3-8) by superior forces (331 battalions and 128 hundreds against 82 battalions of the 9th German Army) was repulsed with heavy losses for the Russians. The offensive of the Northern Front from the Riga bridgehead also turned out to be ineffective, and the German command continued to transfer troops from areas north of Polesie to the south.

In July, the Headquarters transferred the guard and strategic reserve to the south, creating the Special Army of General Bezobrazov, and ordered the Southwestern Front to capture Kovel. On July 15 (28), the Southwestern Front launched a new offensive. Attacks of the fortified marshy defiles on Stokhod against German troops ended in failure. The 11th Army of the Southwestern Front took Brody, and the 7th Army took Galich. The 9th Army of General N.A. Lechitsky achieved significant success in July-August, occupying Bukovina and taking Stanislav.

By the end of August, the offensive of the Russian armies ceased due to the increased resistance of the Austro-German troops, as well as heavy losses and fatigue of personnel.

Results

As a result of the offensive operation, the Southwestern Front inflicted a serious defeat on the Austro-Hungarian troops in Galicia and Bukovina. The losses of the Central Powers, according to Russian estimates, amounted to about one and a half million people killed, wounded and captured. The high losses suffered by the Austrian troops further reduced their combat effectiveness. To repel the Russian offensive, Germany transferred 11 infantry divisions from the French theater of operations, and Austria-Hungary transferred 6 infantry divisions from the Italian front, which became a tangible aid to Russia’s Entente allies. Under the influence of the Russian victory, Romania decided to enter the war on the side of the Entente, although the consequences of this decision are assessed ambiguously by historians.

The result of the offensive of the Southwestern Front and the operation on the Somme was the final transition of the strategic initiative from the Central Powers to the Entente. The Allies managed to achieve such interaction that for two months (July-August) Germany had to send its limited strategic reserves to both the Western and Eastern Fronts.

At the same time, the Russian army's summer campaign in 1916 demonstrated serious shortcomings in troop management. The headquarters was unable to implement the plan for a general summer offensive of three fronts agreed upon with the allies, and the auxiliary attack of the Southwestern Front turned out to be the main one offensive operation. The offensive of the Southwestern Front was not supported in a timely manner by other fronts. The headquarters did not show sufficient firmness towards General Evert, who repeatedly disrupted the planned timing of the offensive of the Western Front. As a result, a significant part of the German reinforcements against the Southwestern Front came from other sectors of the Eastern Front.

The July offensive of the Western Front on Baranovichi revealed the inability of the command staff to cope with the task of breaking through a heavily fortified German position, even with a significant superiority in forces.

Since the June Lutsk breakthrough of the 8th Army was not provided for by the Headquarters plan, it was not preceded by the concentration of powerful front-line reserves, therefore neither the 8th Army nor the Southwestern Front could develop this breakthrough. Also, due to the fluctuations of the Headquarters and the command of the Southwestern Front during the July offensive, the 8th and 3rd armies reached the river by July 1 (14). Stokhod without sufficient reserves and were forced to stop and wait for the approach of the Special Army. Two weeks of respite gave the German command time to transfer reinforcements, and subsequent attacks by Russian divisions were repulsed. “The impulse cannot stand a break.”

It is for these reasons that some military historians will call the successful operation of the Southwestern Front a “lost victory.” The huge losses of the Russian army in the operation (according to some sources, up to half a million people in the SWF alone on June 13) required additional recruitment of recruits, which at the end of 1916 increased dissatisfaction with the war among the Russian population.