Ryu fastening on ships of the 17th century. Orazio Curti European shipbuilding in the 17th - early 18th centuries

Source: Central Maritime Club DOSAAF RSFSR. Publishing house DOSAAF. Moscow, 1987

§1. Spar.

A spar is the name given to all wooden, and on modern ships, metal parts that are used to carry sails, flags, raise signals, etc. The masts on a sailing ship include: masts, topmasts, yards, gaffs, booms, bowsprits, props, spears and shotguns.

Masts.

Salings and ezelgofts, depending on their location and belonging to a particular mast, also have their own names: for-saling, for-bram-saling, mast ezelgoft. for-sten-ezelgoft, kruys-sten-ezelgoft, bowsprit ezelgoft (connecting the bowsprit with the jib), etc.

Bowsprit.

A bowsprit is a horizontal or slightly inclined beam (inclined mast), protruding from the bow of a sailing ship, and used to carry straight sails - a blind and a bomb blind. Until the end of the 18th century, the bowsprit consisted of only one tree with a blind topmast (), on which straight blind and bomb blind sails were installed on the blind yard and bomb blind yard.

Since the end of the 18th century, the bowsprit has been lengthened with the help of a jib, and then a bom-blind (), and blind and bomb-blind sails are no longer installed on it. Here it serves to extend the stays of the foremast and its topmasts and to attach the bow triangular sails - jibs and staysails, which improved the propulsion and agility of the ship. At one time, triangular sails were combined with straight ones.

The bowsprit itself was attached to the bow of the ship using a water-vuling made of a strong cable, and later (19th century) and chains. To tie the wooling, the main end of the cable was attached to the bowsprit, then the cable was passed through the hole in the bowdiged, around the bowsprit, etc. Usually they installed 11 hoses, which were tightened in the middle with transverse hoses. From the sliding of the guards and stays along the bowsprit, several wooden attachments were made on it - bis ().

Bowstrits with a jib and bom-jib had a vertical martin boom and horizontal blind gaffs for carrying the standing rigging of the jib and bom-jib.

Rhea.

A ray is a round, spindle-shaped spar that tapers evenly at both ends, called noks ().

Shoulders are made at both legs, close to which perts, slings of blocks, etc. are pinned. Yards are used for attaching straight sails to them. The yards are attached in the middle to the masts and topmasts in such a way that they can be raised, lowered and rotated horizontally to set the sails in the most advantageous position relative to the wind.

At the end of the 18th century, additional sails appeared - foxes, which were placed on the sides of the main sails. They were attached to small yards - lisel-spirits, extended to the sides of the ship along the main yard through the yoke ().

Yards also take names depending on their belonging to one or another mast, as well as on their location on the mast. So, the names of the yards on various masts, counting them from bottom to top, are as follows: on the foremast - fore-yard, fore-mars-yard, fore-front-yard, fore-bom-front-yard; on the main mast - main-yard, main-marsa-ray, main-bram-ray, main-bom-bram-ray; on the mizzen mast - begin-ray, cruisel-ray, cruis-bram-ray, cruis-bom-bram-ray.

Gaffs and booms.

The gaff is a special yard, strengthened obliquely at the top of the mast (behind it) and raised up the mast. On sailing ships it was used to fasten the upper edge (luff) of the oblique sail - trysail and oblique mizzen (). The heel (inner end) of the gaff has a wooden or metal mustache covered with leather, holding the gaff near the mast and encircling it like a grab, both ends of which are connected to each other by a bayfoot. Bayfoot can be made of vegetable or steel cable, covered with leather or with balls placed on it, the so-called raks-klots.

To set and remove sails on ships with oblique rigs and mizzen oblique sails, the gaff is raised and lowered with the help of two running rigging gear - a gaff-gardel, which lifts the gaff by the heel, and a dirik-halyard, which lifts the gaff by the toe - the outer thin end ().

On ships with direct rigging, the oblique sails - trysails - are pulled (when they are retracted) to the gaff by gaffs, but the gaff is not lowered.

Booms are used to stretch the lower luff of oblique sails. The boom is movably fastened with a heel (the inner end to the mast using a swivel or mustache, like a gaff (). The outer end of the boom (knob) when the sail is set is supported by a pair of topenants, strengthened on one side and the other of the boom.

Gaffs and booms, armed with an oblique sail on the mizzen, began to be used in the Russian fleet approximately from the second half of the 18th century, and in the times of Peter the Great, a Latin yard (ryu) was hung obliquely on the mizzen to carry a Latin triangular sail. Such a yard was raised in an inclined position so that one leg (rear) was raised high, and the other was lowered almost to the deck ()

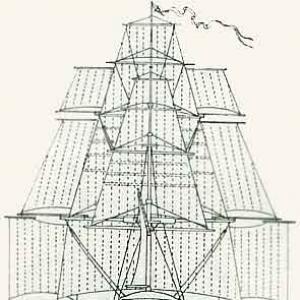

Having familiarized ourselves with each spar tree separately, we will now list all the spar trees according to their location on the sailing ship, with their full name ():

I - knyavdiged; II - latrine; III - crumble; IV - bulwark, on top of it - sailor's bunks; V - fore-beam and stay-stays; VI - mainsail channel and stay cables; VII - mizzen channel and shrouds; VIII - right sink: IX - balconies; X - main-wels-barhout; XI - chanel-wels-barhout: XII - shir-wels-barhout; XIII - shir-strek-barkhout; XIV - rudder feather.

| Rice. 9. Spar of a three-deck 126-gun battleship from the mid-19th century. |

| 1 - bowsprit; 2 - jig; 3 - bom-fitter; 4 - martin boom; 5 - gaff blind; 6 - bowsprit ezelgoft; 7 - rod guy; 8 - foremast; 9 - top of the foremast; 10 - fore-trisail mast; 11 - topmasts; 12 - mast ezelgoft; 13 - fore topmast; 14 - top fore-topmast; 15 - for-saling; 16 - ezelgoft fore-topmast; 17 - fore topmast, made into one tree with fore top topmast; 18-19 - top forebom topmast; 20 - klotik; 21 - fore-beam; 22 - for-marsa lisel-alcohols; 23 - fore-mars-ray; 24 - for-bram-lisel-alcohols; 25 - fore-frame; 26 - for-bom-bram-ray; 27 -for-trisel-gaff; 28 - mainmast; 29 - top of the mainmast; 30 - main-trisail-mast; 31 - mainsail; 32 - mast ezelgoft; 33 - main topmast; 34 - top of the main topmast; 35 - main saling; 36 - ezelgoft main topmast; 37 - main topmast, made into one tree with the main topmast; 38-39 - top main-bom-topmast; 40 - klotik; 41 - grottoes; 42 - grotto-marsa-lisel-spirits; 43 - main-marsa-ray; 44 - main-bram-foil-spirits; 45 - main beam; 46 - main-bom-bram-ray; 47 - mainsail-trisail-gaff; 48 - mizzen mast; 49 - top of the mizzen mast; 50 - mizzen-trysel-mast; 51 - cruise-mars; 52 - mast ezelgoft: 53 - topmast; 54 - top cruise topmast; 55 -kruys-saling; 56 - ezelgoft topmast; 57 - cruising topmast, made into one tree with cruising topmast; 58-59 - top cruise-bom-topmast; 60 - klotik; 61 - begin-ray; 62 - cruise-marsa-rey or cruisel-ray; 63 - cruise-bram-ray; 64 - cruise-bom-bram-ray; 65 - mizzen boom; 66 - mizzen-gaff: 67 - stern flagpole. |

§2. Basic proportions of spar trees for battleships.

The length of the mainmast is determined by the length of the ship along the gondeck, folded to its greatest width and divided in half. The length of the foremast is 8/9, and the mizzen mast is 6/7 the length of the mainmast. The length of the main and foremast tops is 1/6, and the mizzen mast top is 1/8-2/13 of their length. The largest diameter of the masts is located at the forward deck and is 1/36 for the foremast and main mast, and 1/41 of their length for the mizzen mast. The smallest diameter is under the top and is 3/5-3/4, and the spur has 6/7 of the largest diameter.

The length of the main topmast is equal to 3/4 of the length of the main mast. The length of the topmasts is 1/9 of the entire length of the topmast. The largest diameter of the topmasts is found in mast ezelgofts and is equal to 6/11 of the diameter of the mainmast for the main and fore topmasts, and 5/8 of the diameter of the mizzen mast for the cruise topmast. The smallest diameter under the top is 4/5 of the largest.

The length of the topmasts, made into one tree with the boom topmasts and their flagpoles (or tops), is made up of: the length of the topmast equal to 1/2 of its topmast, the boom topmast - 5/7 of its topmast topmast and flagstaff equal to 5/7 of its topmast. The largest diameter of the topmast at the ezelgoft wall is 1/36 of its length, the boom topmast is 5/8 of the topmast diameter, and the smallest diameter of the flagpole is 7/12 of the topmast diameter.

The length of the bowsprit is 3/5 of the length of the mainmast, the largest diameter (at the bulwark above the stem) is equal to the diameter of the mainmast or 1/15-1/18 less than it. The lengths of the jib and bom jib are 5/7 of the length of the bowsprit, the largest diameter of the jib is 8/19, and the bom jib is 5/7 of the diameter of the bowsprit is 1/3 from their lower ends, and the smallest is at the legs - 2/3 largest diameter.

The length of the main yard is equal to the width of the ship multiplied by 2 plus 1/10 of the width. The total length of both legs is 1/10, and the largest diameter is 1/54 of the length of the yard. The length of the main-tops-yard is 5/7 of the main-yard, the legs are 2/9, and the largest diameter is 1/57 of the length of the main-tops-yard. The length of the main top-yard is 9/14 of the main top-yard, the legs are 1/9 and the largest diameter is 1/60 of this yard. All sizes of the fore-yard and fore-tops-yard are 7/8 of the size of the mainsail and main-tops-yard. The Begin-ray is equal to the main-marsa-yard, but the length of both legs is 1/10 of the length of the yard, the cruisel-yard is equal to the main-bram-yard, but the length of both legs is 2/9 of the length of the yard, and the cruis-brow-yard equal to 2/3 of the main beam. All bom-bram-yards are equal to 2/3 of their bram-yards. Blinda-ray is equal to for-Mars-ray. The largest diameter of the yards is in their middle. The yards from the middle to each end are divided into four parts: on the first part from the middle - 30/31, on the second - 7/8, on the third - 7/10 and at the end - 3/7 of the largest diameter. The mizzen boom is equal to the length and thickness of the fore- or main-tops yard. Its largest diameter is above the tailrail. The mizzen gaff is 2/3 long, and the boom is 6/7 thick, its largest diameter is at the heel. The length of the martin booms is 3/7, and the thickness is 2/3 of a jig (there were two of them until the second quarter of the 19th century).

The main topmast is 1/4 the length of the main topmast and 1/2 the width of the ship. The fore-topsight is 8/9, and the cruise-topsight is 3/4 of the main topsea. The main saling has long salings 1/9 the length of its topmast, and spreaders 9/16 the width of the topsail. For-saling is equal to 8/9, and kruys-saling is 3/4 of grot-saling.

§3. Standing rigging spar.

The bowsprit, masts and topmasts on a sailing ship are secured in a specific position using special rigging called standing rigging. Standing rigging includes: shrouds, forduns, stays, backstays, perths, as well as the jib and boom jib of the lifeline.

Once wound, the standing rigging always remains motionless. Previously it was made from thick plant cable, and on modern sailing ships it was made from steel cable and chains.

Shrouds are the name given to standing rigging gear that strengthens masts, topmasts and topmasts from the sides and somewhat from the rear. Depending on which spar tree the cable stays hold, they receive additional names: fore-stays, fore-wall-stays, fore-frame-wall-stays, etc. The shrouds also serve to lift personnel onto masts and topmasts when working with sails. For this purpose, hemp, wood or metal castings are strengthened across the cables at a certain distance from each other. Hemp bleachings were tied to the shrouds with a bleaching knot () at a distance of 0.4 m from one another.

The lower shrouds (hemp) were made the thickest on sailing ships, their diameter on battleships reached up to 90-100 mm, the wall-shrouds were made thinner, and the top-wall-shrouds were even thinner. The shrouds were thinner than their shrouds.

The topmasts and topmasts are additionally supported from the sides and somewhat from the rear by forduns. Forduns are also named after the masts and topmasts on which they stand. For example, for-sten-forduns, for-bram-sten-forduns, etc.

The upper ends of the shrouds and forduns are attached to the mast or topmast using ogons (loops) put on the tops of masts, topmasts and topmasts (). Guys, wall-guys and frame-wall-guys are made in pairs, i.e. from one piece of cable, which is then folded and cut according to the thickness of the top on which it is applied. If the number of shrouds on each side is odd, then the last shroud to the stern, including the forduns, are made split (). The number of shrouds and forearms depends on the height of the mast and the carrying capacity of the vessel.

The shrouds and forduns were stuffed (tightened) with cable hoists on deadeyes - special blocks without pulleys with three holes for a cable lanyard, with the help of which the shrouds and forduns are stuffed (tensioned). On modern sailing ships, the rigging is covered with metal screw shrouds.

In former times, on all military sailing ships and large merchant ships, in order to increase the angle at which the lower shrouds and forduns go to the masts, powerful wooden platforms - rusleni () - were strengthened on the outer side of the ship, at deck level.

| Rice. 11. Tightening the shrouds with deadeyes. |

The shrouds were secured with shrouds forged from iron strips. The lower end of the shrouds was attached to the side, and the deadeyes were attached to their upper ends so that the latter almost touched their lower part with the channel.

The upper deadeyes are tied into the shrouds and forduns using lights and benzels (marks) (). The root end of the lanyard is attached to the hole in the shroud-jock using a turnbuckle button, and the running end of the lanyard, after tightening the shrouds, having made several slags around them, is attached to the shroud using two or three benzels. Having established turnbuckles between all the deadeyes of the lower shrouds, they tied an iron rod to them on top of the deadeyes - vorst (), which prevented the deadeyes from twisting, keeping them at the same level. The topmast shrouds were equipped in the same way as the lower shrouds, but their deadeyes were somewhat smaller.

The standing rigging gear that supports the spars (masts and topmasts) in the center plane in front is called forestays, which, like the lower shrouds, were made of thick cable. Depending on which spar tree the stays belong to, they also have their own names: fore-stay, fore-stay-stay, fore-stay, etc. The headlights of the stays are made the same as those of the shrouds, but their sizes are larger (). The forestays are stuffed with lanyards on forestay blocks ().

Standing rigging also includes perths - plant ropes on yards (see), on which sailors stand while working with sails on yards. Usually one end of the perts is attached to the end of the yardarm, and the other in the middle. The perths are supported by props - sections of cable attached to the yard.

Now let's see what the complete standing rigging will look like on a sailing 90-gun, two-deck battleship of the late 18th and early 19th centuries with its full name (): 1 - water stays; 2 - Martin stay; 3 - Martin stay from the boom stay (or lower backstay); 4 - forestay; 5 - for-elk-stay; 6 - fore-elk-stay-stay (serves as a rail for the fore-top-staysail); 7 - fore-stay-stay; 8 - jib-rail; 9 - fore-gateway-wall-stay; 10 - boom-jib-rail; 11 - fore-bom-gateway-wall-stay; 12 - mainstay; 13 - main-elk-stay; 14 - main-elk-wall-stay; 15-mainsail-stay; 18 - mizzen stay; 19 - cruise-stay-stay; 20 - cruise-brow-stay-stay; 21 - cruise-bom-bram-wall-stay; 22 water tank stays; 23 - jib-backstays; 24 - boom-jumper-backstays; 25 - fore shrouds; 26 - fore-wall-shrouds; 27-fore-frame-wall-shrouds; 28 - for-sten-forduns; 29 - for-bram-wall-forduns; 30 - for-bom-bram-sten-forduns; 31 - main shrouds; 32 - main-wall-shrouds; 33 - main-frame-wall-shroud; 34 - main-sten-forduns; 35 - grotto-gateway-wall-forduny; 36 - grotto-bom-bram-wall-forduny; 37 - mizzen shrouds; 38 - cruise-wall-shroud; 39 - cruise-bram-wall-shroud; 40 - kruys-sten-forduny; 41 - kruys-bram-sten-forduny; 42 - kruys-bom-bram-sten-fortuny.

§4. The order of application, places of traction and thickness of hemp standing rigging.

Water stays, 1/2 thick of the bowsprit, are inserted into a hole in the leading edge of the bowsprit, attached there and raised to the bowsprit, where they are pulled by cable turnbuckles located between the deadeyes. The water backstays (one on each side) are hooked behind the butts, driven into the hull under the crimps, and are pulled from the bowsprit like water stays.

Then the shrouds are applied, which are made in pairs, with a thickness of 1/3 of their mast. Each end assigned to a pair of cables is folded in half and a bend is made at the bend using a benzel. First, the front right, then the front left pair of shrouds, etc. are put on the top of the mast. If the number of cables is odd, then the latter is made split, i.e. single. The shrouds are pulled by cable lanyards, based between the deadeyes tied into the lower ends of the shrouds, and the deadeyes fastened at the channel with the shrouds. Fore and main stays are made 1/2 thick, mizzen stays - 2/5 of their masts, and elk stays - 2/3 of their stays (hemp cables are measured along the circumference, and spars - according to the largest diameter).

They are put on the tops of the masts so that they cover the long-salings with the lights. The forestay and forestay are pulled by cable turnbuckles on the bowsprit, the mainstay and mainstay are on the deck on the sides and in front of the foremast, and the mizzen stay branches into legs and is attached to the deck on the sides of the mainstay. mast or passes through the thimble on the mainmast and stretches on the deck.

The main-shrouds, 1/4 thick of their topmasts, are pulled on the top platform by turnbuckles, mounted between the deadeyes tied into the main-shrouds and the deadeyes fastened to the eye-shrouds. The topmasts, 1/3 of the thickness of their topmasts, stretch on the channels like shrouds. The mainstays have a thickness of 1/3, and the elk-stays have a thickness of 1/4 of their topmasts, the fore-stay-stay is carried into a pulley on the right side of the bowsprit, and the fore-stay-stay - on the left. The main-stay-stay and the main-elk-stay-stay are carried through the pulleys of the blocks on the foremast and are pulled by the gypsum on the deck. The stay-stay cruise passes through the block pulley on the mainmast and extends on the topsail.

The standing rigging of the jib and boom jib is made 1/4 thick of its spar trees. Each marin stay is passed sequentially into the holes of its martin boom (there are two of them), where it is held with a button, then into the pulley of the block on the toe of the jig, into the pulley on the martin boom and on the bowsprit, and is pulled onto the forecastle. The jib backstays (two on each side) are tied with the middle end to the jib of the jib, their ends are inserted into thimbles near the legs of the blind yard and are pulled on the forecastle. The bom-jugger-backstay is also applied and pulled. The Martin stay from the boom jib is attached with the middle end to the end of the jib jib. and passing through the pulleys on the martin boom and bowsprit, it stretches to the forecastle.

The top stays and top stays are made 2/5 thick, and the top stays are made 1/2 of their top topmasts. The top shrouds are passed through holes in the saling spreaders, pulled up to the topmast and descended along the top shrouds to the top, where they are pulled by turnbuckles through thimbles at their ends. The fore-forestay passes into a pulley at the end of the jib and stretches on the forecastle, the main-forestay goes into a pulley on the fore-topmast, and the cruise-forestay goes into a pulley at the top of the mainmast and both are pulled on the deck.

Bom-bram-rigging is carried out and pulled like a bram-rigging.

§5. Running rigging spar.

Running rigging of a spar refers to all movable gear through which work is carried out related to lifting, selecting, pickling and turning spar trees - yards, gaffs, shots, etc.

The running rigging of the spar includes girdles and driers. halyards, braces, topenants, sheets, etc.

On ships with direct sails, the guards are used to raise and lower the lower yards with sails (see) or gaffs (its heels); dryropes for lifting the topsails, and halyards for lifting the top-yards and boom-yards, as well as oblique sails - jibs and staysails.

The tackle with which the toe of the gaff is raised and supported is called a dirik-halyard, and the tackle that lifts the gaff by the heel along the mast is called a gaff-gardel.

The gear that serves to support and level the ends of the yards is called topenants, and for turning the yards - brahms.

Now let's get acquainted with all the running rigging of the spar, with its full names, according to its location on the ship ():

Gear used for raising and lowering the yards: 1 - fore-yard girdle; 2 - for-mars-drayrep; 3 - fore-tops-halyard; 4 - fore-bram-halyard; 5 - fore-bom-bram-halyard; 6 - gardel of the mainsail; 7 - main-marsa-drayrep; 8 - mainsail-halyard; 9 main halyard; 10 - main-bom-brow-halyard; 11 - gardel-begin-ray; 12 - cruise-topsail-halyard; 13 - cruise-marsa-drairep; 14 - cruise halyard; 15 - cruise-bom-bram-halyard; 16 - gaff-gardel; 17 - dirk-halyard.

Gear used to support and level the ends of the yards: 18 - blind-toppenants; 19 - foka-topenants; 20 - fore-mars-topenants; 21 - for-bram-topenants; 22 - for-bom-bram-topenants; 23 - mainsail-topenants; 24 - main-mars-topenants; 25 - main-frame-topenants; 26 - main-bom-bram-topenants; 27 - beguin-topenants; 28 - cruise-marsa-topenants; 29 - cruis-bram-topenants; 30-kruys-bom-bram-topenants; 31 - mizzen-geek-topenants; 31a - mizzen-geek-topenant pendant.

Gear used for turning the yards: 32 - blind-tris (bram-blinda-yard); 33 - fore-braces; 34 - fore-tops-braces; 35 - fore-braces; 36 - fore-bom-braces; 37 - main-contra-braces; 38 - mainsail braces; 39 - main-topsail-braces; 40 - main-frame-braces; 41 - main-bom-braces; 42 - beguin braces; 43 - cruise-tops-braces; 44 - cruise-braces; 45 - cruise-bom-braces; 46 - Erins backstays; 47 - blockage; 48 - mizzen-gym-sheet.

§6. Wiring of the running rigging shown in.

The foresail and mainsail are based between two or three-pulley blocks, two are strengthened under the topsail and two near the middle of the yard. The begin-gardel is based between one three-pulley block under the topsail and two single-pulley blocks on the yard. The running ends of the guards are mounted on bollards.

The fore- and main-mars-drires are attached with the middle end to the topmast, their running ends are each carried into their own blocks on the yardarm and under the saling, and blocks are woven into their ends. Marsa halyards are based between these blocks and the blocks on the riverbeds. Their flaps are pulled through the side bollards. The cruisel-marsa-drayrep is taken with its root end in the middle of the yard, and the running gear is passed through a pulley in the topmast under the saling and a block of the top-sailing halyard is inserted into its end, which is based on a mantyl - the root end is attached to the left channel, and the hoist to the right.

The top and boom halyards are taken with the root end in the middle of their yard, and the running ends are guided into the pulley of their topmast and pulled by the hulls: the top halyards are on the deck, and the boom halyards are on the topside.

The gaff-gardel is based between the block on the heel of the gaff and the block under the cruis-tops. The main end of the halyard is attached to the top of the topmast, and the running end is carried through the blocks on the gaff and the top of the mast. Their running ends are attached to bollards.

The blind-toppings are based between the blocks on both sides of the bowsprit eselgoft and on the ends of the blind-yard, and their flaps stretch on the forecastle. The foresail and main-topenants are based between three- or two-pulley blocks, and the beguin-topenants are based between two- or single-pulley blocks on both sides of the mast ezelgoft and on both ends of the yards. Their running ends, passed through the “dog holes”, are attached to bollards. The middle end of the top-stops is attached to the topmast, and the running ends, taken with a half-bayonet by the front shrouds, are inserted into blocks on the yard legs, into the lower pulleys of the butt blocks. through the “dog holes” and are attached next to the lower topenants. The bram- and bom-bram-topenants are put on with a point on the legs of the yard and, carried through the blocks on their topmasts, stretch: the bram-toppenant on the deck, and the bom-bram-topenants on the topsail. The boom-topenants are taken with the middle end of the boom leg, carried out on both sides of it, as shown in the figure, and pulled with grips at the heel of the boom.

The fore-braces are attached with the middle end to the top of the mainmast, are carried, as can be seen in the figure, and are pulled on the bollards of the mainmast. The main-braces are based between the blocks at the side of the poop and on the legs of the main-yard and extend through the side bollards. The main-contra-braces are based on top of the fore-braces between the blocks on the foremast and the yard legs and extend at the foremast. The main ends of the begin braces are taken by the rear main shrouds, and the running gears are passed through blocks on the yard legs and on the rear main shrouds and are attached to the tile strip at the side. Mars braces are attached at the middle end to the topmast, are carried into the shrouds, as shown in the figure, and are pulled on the deck. The fore- and main-braces are attached with the middle end to the gate or boom-brow-topmast and are carried into blocks at the ends of the yards and into blocks near the main end and stretch along the deck. Cruys-brams and all bom-brass are put on the ends of their yards, held as shown in the figure, and pulled on the deck.

Battleship(English) ship-of-the-line, fr. navire de ligne) - a class of sailing three-masted wooden warships. Sailing battleships were characterized by the following features: a total displacement from 500 to 5500 tons, armament, including from 30-50 to 135 guns in the side ports (in 2-4 decks), the crew size ranged from 300 to 800 people when fully manned. Ships of the line were built and used from the 17th century until the early 1860s for naval battles using linear tactics. Sailing battleships were not called battleships.

General information

In 1907, a new class of armored ships with a displacement from 20 thousand to 64 thousand tons was called battleships (abbreviated as battleships).

History of creation

“In times long past... on the high seas, he, a battleship, was not afraid of anything. There was not a shadow of a feeling of defenselessness from possible attacks by destroyers, submarines or aircraft, nor trembling thoughts about enemy mines or air torpedoes, there was essentially nothing, with the possible exception of a severe storm, drift to a leeward shore, or a concentrated attack by several equal opponents, which could shake the proud confidence of a sailing battleship in its own indestructibility, which it assumed with every right." - Oscar Parks. Battleships of the British Empire.

Technological innovations

Many related technological advances led to the emergence of battleships as the main force of navies.

The technology of building wooden ships, considered today to be classical - first the frame, then the plating - finally took shape in Byzantium at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennia AD, and thanks to its advantages, over time it replaced the previously used methods: the Roman one used in the Mediterranean, with smooth lining boards, the ends of which were connected with tenons, and clinker, which was used from Russia to the Basque Country in Spain, with overlapping cladding and transverse reinforcement ribs inserted into the finished body. In southern Europe, this transition finally took place before the middle of the 14th century, in England - around 1500, and in Northern Europe, merchant ships with clinker lining (holkas) were built back in the 16th century, possibly later. In most European languages, this method was denoted by derivatives of the word carvel; hence the caravel, that is, initially, a ship built starting from the frame and with the skin smooth.

The new technology gave shipbuilders a number of advantages. The presence of a frame on the ship made it possible to accurately determine in advance its dimensions and the nature of its contours, which, with the previous technology, became fully obvious only during the construction process; ships are now built according to a pre-approved plan. In addition, the new technology made it possible to significantly increase the size of ships - both due to greater hull strength and due to reduced requirements for the width of the boards used for plating, which made it possible to use lower quality wood for the construction of ships. The qualification requirements for the workforce involved in construction were also reduced, which made it possible to build ships faster and in much larger quantities than before.

In the 14th-15th centuries, gunpowder artillery began to be used on ships, but initially, due to the inertia of thinking, it was placed on superstructures intended for archers - the forecastle and sterncastle, which limited the permissible mass of the guns for reasons of maintaining stability. Later, artillery began to be installed along the side in the middle of the ship, which largely removed the restrictions on the mass of the guns, but aiming them at the target was very difficult, since the fire was fired through round slots made to the size of the gun barrel in the sides, which were plugged from the inside in the stowed position. Real gun ports with covers appeared only towards the end of the 15th century, which paved the way for the creation of heavily armed artillery ships. During the 16th century, a complete change in the nature of naval battles occurred: rowing galleys, which had previously been the main warships for thousands of years, gave way to sailing ships armed with artillery, and boarding combat to artillery.

Mass production of heavy artillery guns for a long time was very difficult, therefore, until the 19th century, the largest ones installed on ships remained 32...42-pounders (based on the mass of the corresponding solid cast-iron core), with a bore diameter of no more than 170 mm. But working with them during loading and aiming was very complicated due to the lack of servos, which required a huge calculation for their maintenance: such guns weighed several tons each. Therefore, for centuries, they tried to arm ships with as many relatively small guns as possible, which were located along the side. At the same time, for reasons of strength, the length of a warship with a wooden hull is limited to approximately 70-80 meters, which also limited the length of the onboard battery: more than two to three dozen guns could only be placed in several rows. This is how warships arose with several closed gun decks (decks), carrying from several dozen to hundreds or more guns of various calibers.

In the 16th century, cast iron cannons began to be used in England, which were a great technological innovation due to their lower cost relative to bronze and less labor-intensive manufacturing compared to iron ones, and at the same time possessing higher characteristics. Superiority in artillery manifested itself during the battles of the English fleet with the Invincible Armada (1588) and has since begun to determine the strength of the fleet, making boarding battles history - after which boarding is used exclusively for the purpose of capturing an enemy ship that has already been disabled by fire from the guns of an enemy ship.

In the middle of the 17th century, methods for mathematical calculation of ship hulls appeared. Introduced into practice around the 1660s by the English shipbuilder A. Dean, the method of determining the displacement and waterline level of a ship based on its total mass and the shape of its contours made it possible to calculate in advance at what height from the sea surface the ports of the lower battery would be located, and to position the decks accordingly and the guns are still on the slipway - previously this required lowering the ship’s hull into the water. This made it possible to determine the firepower of the future ship at the design stage, as well as to avoid accidents like what happened with the Swedish Vasa due to the ports being too low. In addition, on ships with powerful artillery, part of the gun ports necessarily fell on the frames; Only real frames, not cut by ports, were power-bearing, and the rest were additional, so precise coordination of their relative positions was important.

History of appearance

The immediate predecessors of battleships were heavily armed galleons, carracks and the so-called “big ships” (Great Ships). The first purpose-built gunship is sometimes considered to be the English carrack. Mary Rose(1510), although the Portuguese attribute the honor of their invention to their king João II (1455-1495), who ordered the arming of several caravels with heavy guns.

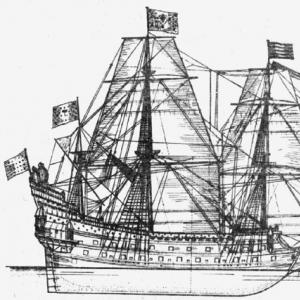

The first battleships appeared in the fleets of European countries at the beginning of the 17th century, and the first three-decker battleship is considered HMS Prince Royal(1610) . They were lighter and shorter than the “tower ships” that existed at that time - galleons, which made it possible to quickly line up with the side facing the enemy, when the bow of the next ship looked at the stern of the previous one. Also, battleships differ from galleons in having straight sails on a mizzen mast (galleons had from three to five masts, of which usually one or two were “dry”, with oblique sails), the absence of a long horizontal latrine at the bow and a rectangular tower at the stern , and maximum use of the free area of the sides for the guns. A battleship is more maneuverable and stronger than a galleon in artillery combat, while a galleon is better suited for boarding combat. Unlike battleships, galleons were also used to transport troops and trade cargo.

The resulting multi-deck sailing battleships were the main means of warfare at sea for more than 250 years and allowed countries such as Holland, Great Britain and Spain to create huge trading empires.

By the middle of the 17th century, a clear division of battleships by class arose: the old two-deck (that is, in which two closed decks one above the other were filled with cannons firing through ports - slits in the sides) ships with 50 guns were not strong enough for linear battle and were used in mainly for escorting convoys. Double-decker battleships, carrying from 64 to 90 guns, made up the bulk of the navy, while three- or even four-decker ships (98-144 guns) served as flagships. A fleet of 10-25 such ships made it possible to control sea trade lines and, in the event of war, close them to the enemy.

Battleships should be distinguished from frigates. Frigates had either only one closed battery, or one closed and one open battery on the upper deck. The sailing equipment of battleships and frigates was the same (three masts, each with straight sails). Battleships were superior to frigates in the number of guns (several times) and the height of their sides, but they were inferior in speed and could not operate in shallow water.

Battleship tactics

| With the increase in the strength of the warship and with the improvement of its seaworthiness and fighting qualities, an equal success has appeared in the art of using them... As sea evolutions become more skillful, their importance grows day by day. These evolutions needed a base, a point from which they could depart and to which they could return. A fleet of warships must always be ready to meet the enemy; it is logical that such a base for naval evolution should be a combat formation. Further, with the abolition of galleys, almost all the artillery moved to the sides of the ship, which is why it became necessary to always keep the ship in such a position that the enemy was abeam. On the other hand, it is necessary that not a single ship in its fleet can interfere with firing at enemy ships. Only one system can fully satisfy these requirements, this is the wake system. The latter, therefore, was chosen as the only combat formation, and therefore as the basis for all fleet tactics. At the same time, they realized that in order for the battle formation, this long thin line of guns, not to be damaged or torn at its weakest point, it is necessary to introduce into it only ships, if not of equal strength, then at least with equal strength. strong sides. It logically follows from this that at the same time as the wake column becomes the final battle formation, a distinction is established between battleships, which alone are intended for it, and smaller vessels for other purposes. Mahan, Alfred Thayer |

The term “battleship” itself arose due to the fact that in battle, multi-deck ships began to line up one after another - so that during their salvo they would be turned broadside to the enemy, because the greatest damage to the target was caused by a salvo from all onboard guns. This tactic was called linear. Formation in a line during a naval battle first began to be used by the fleets of England and Spain at the beginning of the 17th century and was considered the main one until the middle of the 19th century. Linear tactics also did a good job of protecting the squadron leading the battle from attacks by fireships.

It is worth noting that in a number of cases, fleets consisting of battleships could vary tactics, often deviating from the canons of the classic firefight of two wake columns running parallel courses. Thus, at Camperdown, the British, not having time to line up in the correct wake column, attacked the Dutch battle line with a formation close to the front line followed by a disorderly dump, and at Trafalgar they attacked the French line with two columns running across each other, wisely using the advantages of longitudinal fire, striking not separated by transverse bulkheads caused terrible damage to wooden ships (at Trafalgar, Admiral Nelson used tactics developed by Admiral Ushakov). Although these were extraordinary cases, even within the framework of the general paradigm of linear tactics, the squadron commander often had sufficient space for bold maneuver, and the captains for exercising their own initiative.

Design features and combat qualities

The wood for the construction of battleships (usually oak, less often teak or mahogany) was selected with the most care, soaked and dried for a number of years, after which it was carefully laid in several layers. The side skin was double - inside and outside of the frames; the thickness of one outer skin on some battleships reached 60 cm at the gondeck (at the Spanish Santisima Trinidad), and the total internal and external - up to 37 inches, that is, about 95 cm. The British built ships with relatively thin plating, but often spaced frames, in the area of which the total thickness of the side of the gondeck reached 70-90 cm of solid wood; between the frames, the total thickness of the side, formed by only two layers of skin, was less and reached 2 feet (60 cm). For greater speed, French battleships were built with thinner frames, but thicker plating - up to 70 cm between frames in total.

To protect the underwater part from rot and fouling, an outer lining of thin strips of soft wood was placed on it, which was regularly changed during the timbering process at the dock. Subsequently, at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, copper cladding began to be used for the same purposes.

- List of men-of-war 1650-1700. Part II. French ships 1648-1700.

- Histoire de la Marine Francaise. French naval history.

- Les Vaisseaux du roi Soleil. Contain for instance list of ships 1661 to 1715 (1-3 rates). Author: J.C Lemineur: 1996 ISBN 2906381225

Notes

For early ships “This name of a warship is a compound abbreviated word that arose in the 20s of the 20th century. based on the phrase battleship." Krylov's Etymological Dictionary https://www.slovopedia.com/25/203/1650517.html

Just because of this museum you can go to Stockholm for the weekend! It took me a long time to write this post, if you are too lazy to read, check out the photos)

Prologue

On August 10, 1628, a large warship sailed from Stockholm harbor. Big, probably an understatement, for the Swedes it was huge. Rarely have they built ships of this scale. The weather was clear, the wind was weak but gusty. There were about 150 crew members on board, as well as their families - women and children (a magnificent celebration was planned on the occasion of the first voyage, so the crew members were allowed to take their family members and relatives with them). This was the newly built Vasa, named after the ruling dynasty. As part of the ceremony, a salute was fired from cannons located in openings on both sides of the ship. There were no signs of trouble; the ship was moving towards the entrance to the harbor. A gust of wind hit, the ship tilted a little but stood firm. The second gust of wind was stronger and threw the ship on its side, and water poured through the open holes for the guns. From that moment on, collapse became inevitable. Perhaps panic began on the ship; not everyone managed to get to the upper deck and jump into the water. But still, most of the team made it. The ship lasted only six minutes on its side. Vasa became the grave of at least 30 people, and fell asleep for 333 years, just like in a fairy tale. Below the cut you will find photographs and a story about the fate of the ship.

02. Take a closer look at him.

03. Vasa was built in Stockholm by order of Gustav Adolf II, King of Sweden, under the direction of the Dutch shipbuilder Henrik Hibertson. A total of 400 people worked on the construction. Its construction took about two years. The ship had three masts, could carry ten sails, its dimensions were 52 meters from the top of the mast to the keel and 69 meters from bow to stern; weight was 1200 tons. By the time construction was completed, it was one of the largest ships in the world.

04. Of course, they are not allowed on the ship; the museum has locations that show what it’s like inside.

05. What went wrong? In the 17th century there were no computers, there were only size tables. But a ship of this level cannot be built “approximately”. High side, short keel, 64 guns on the sides in two tiers, Gustav Adolf II wanted to have more guns on the ship than were usually installed. The ship was built with a high superstructure, with two additional decks for guns. This is what let him down, the center of gravity was too high. The bottom of the ship was filled with large stones, which served as ballast for stability on the water. But "Vasa" was too heavy at the top. As always, little things came up, they put in less ballast (120 tons is not enough) than needed, because they were afraid that the speed would be low, and for some reason a smaller copy was not built either. The comments suggest that there was nowhere else to put more ballast.

06. Vasa was to become one of the leading ships of the Swedish Navy. As I said, he had 64 guns, most of them 24 pounders (they fired cannonballs weighing 24 pounds or over 11 kg). There is a version that they made it for the war with Russia. But at that time the Swedes had more problems with Poland. By the way, they managed to get the guns almost immediately; they were very valuable. England bought the right to raise it. If the guide didn’t lie, these guns were later bought by Poland for the war with Sweden).

07. Why aren’t other ships raised after 300 years? And there is simply nothing left of them. The secret is that the shipworm, Teredo navalis, which devours wooden debris in salt water, is not very common in the slightly salty waters of the Baltic, but in other seas it is quite capable of devouring the hull of an active ship in a short time. Plus, the local water itself is a good preservative; its temperature and salinity are optimal for sailboats.

08. The nose did not enter the lens completely.

09. The lion holds the crown in his paws.

10. There is a copy nearby, you can take a closer look.

11. All faces are different.

12. Look closely at the stern. Initially it was colored and gilded.

13.

14.

15.

16. He was like that, I don’t like him like that. But in the 17th century there were clearly different views on shipbuilding.

17.

18. The life of sailors is cut short, they don’t have their own cabins, everything is done on deck.

19. As for lifting the ship, not everything was simple here either. The ship was found by Anders Franzen, an independent researcher, who had been interested in ship wrecks since childhood. And of course he knew everything about the crash. For several years, a search was carried out with the help of a lot and a cat. "I mostly picked up rusty iron stoves, ladies' bicycles, Christmas trees and dead cats." But in 1956 it took the bait. And Anders Franzen did everything to raise the ship. And he convinced the bureaucrats that he was right, and organized a campaign “Save the Vasa” and from the port dumps he collected and repaired a bunch of various diving equipment that were considered unusable. Money began to flow in and things started to improve, it took two years to build the tunnels under the ship. Tunnels in the literal sense washed under the ship, a dangerous and courageous job. The tunnels were very narrow and the divers had to squeeze through them without getting entangled. And of course, a ship weighing a thousand tons hanging above them did not give courage, Nobody knew whether the Vasa would survive. Nobody else in this the world has not yet raised ships that sank so long ago! But the Vasa survived, did not crumble when sharpened, when divers - mostly amateur archaeologists - entangled its hull with ropes and attached it to hooks lowered into the water from cranes and pontoons - miracle, scientific miracle.

20. For another two years it hung in this state while divers prepared it for lifting, plugging thousands of holes formed by rusty metal bolts. and on April 24, 1961, everything worked out. In that blackened ghost that was brought to the surface, no one would have recognized the same “Vasa”. Years of work lay ahead. Initially, the ship was doused with jets of water, and at this time experts developed a proper conservation method. The chosen preservative material was polyethylene glycol, a water-soluble, viscous substance that slowly penetrates the wood, replacing water. Spraying of polyethylene glycol continued for 17 years.

21. 14,000 lost wooden objects were brought to the surface, including 700 sculptures. Their conservation was carried out on an individual basis; they then took their original places on the ship. The problem was similar to a jigsaw puzzle.

22. Blade handle.

23.

24. The inhabitants of the ship. The bones were extracted in a jumble; without modern technology, nothing would have happened.

25.

26. The museum staff went further than just showing skeletons to visitors. Using "spectral analysis" they reconstructed the faces of some people.

27. They look very close to life.

28. Frightening look.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33. That’s probably all I wanted to tell you. By the way, the ship is 98% original!

34. Thank you for your attention.

Bomber ship

Sailing 2-, 3-masted ship of the late 17th - early 19th centuries. with increased hull strength, armed with smooth-bore guns. They first appeared in France in 1681, in Russia - during the construction of the Azov Fleet. Bombardier ships were armed with 2-18 large-caliber guns (mortars or unicorns) to fight against coastal fortifications and 8-12 small-caliber guns. They were part of the navies of all countries. They existed in the Russian fleet until 1828

Brig

A military 2-masted ship with a square rig, designed for cruising, reconnaissance and messenger services. Displacement 200-400 tons, armament 10-24 guns, crew up to 120 people. It had good seaworthiness and maneuverability. In the XVIII - XIX centuries. brigs were part of all the world's fleets

Brigantine

2-masted sailing ship of the 17th - 19th centuries. with a straight sail on the front mast (foresail) and an oblique sail on the rear mast (mainsail). Used in European navies for reconnaissance and messenger services. On the upper deck there were 6- 8 small caliber guns

Galion

Sailing ship of the 15th - 17th centuries, predecessor of the sailing ship of the line. It had fore and main masts with straight sails and a mizzen with oblique sails. Displacement is about 1550 tons. Military galleons had up to 100 guns and up to 500 soldiers on board

Caravel

A high-sided, single-deck, 3-, 4-mast vessel with high superstructures at the bow and stern, with a displacement of 200-400 tons. It had good seaworthiness and was widely used by Italian, Spanish and Portuguese sailors in the 13th - 17th centuries. Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama made their famous voyages on caravels

Karakka

Sailing 3-mast ship XIV - XVII centuries. with a displacement of up to 2 thousand tons. Armament: 30-40 guns. It could accommodate up to 1200 people. Cannon ports were used for the first time on the karakka and guns were placed in closed batteries

Clipper

A 3-masted sailing (or sail-steam with a propeller) ship of the 19th century, used for reconnaissance, patrol and messenger services. Displacement up to 1500 tons, speed up to 15 knots (28 km/h), armament up to 24 guns, crew up to 200 people

Corvette

A ship of the sailing fleet of the 18th - mid-19th centuries, intended for reconnaissance, messenger service, and sometimes for cruising operations. In the first half of the 18th century. 2-masted and then 3-masted vessel with square rig, displacement 400-600 tons, with open (20-32 guns) or closed (14-24 guns) batteries

Battleship

A large, usually 3-deck (3 gun decks), three-masted ship with square rigging, designed for artillery combat with the same ships in the wake (battle line). Displacement up to 5 thousand tons. Armament: 80-130 smoothbore guns along the sides. Battleships were widely used in wars of the second half of the 17th - first half of the 19th centuries. The introduction of steam engines and propellers, rifled artillery and armor led in the 60s. XIX century to the complete replacement of sailing battleships with battleships

Flutes

A 3-mast sailing ship from the Netherlands of the 16th - 18th centuries, used in the navy as a transport. Armed with 4-6 cannons. It had sides that were tucked inward above the waterline. A steering wheel was used for the first time on a flute. In Russia, flutes have been part of the Baltic Fleet since the 17th century.

Sailing frigate

A 3-masted ship, second in terms of armament power (up to 60 guns) and displacement after a battleship, but superior to it in speed. Intended mainly for operations on sea communications

Sloop

Three-masted ship of the second half of the 18th - early 19th centuries. with straight sails on the forward masts and a slanting sail on the aft mast. Displacement 300-900 tons, artillery armament 16-32 guns. It was used for reconnaissance, patrol and messenger services, as well as a transport and expedition vessel. In Russia, the sloop was often used for circumnavigation of the world (O.E. Kotzebue, F.F. Bellingshausen, M.P. Lazarev, etc.)

Shnyava

A small sailing ship, common in the 17th - 18th centuries. in the Scandinavian countries and in Russia. Shnyavs had 2 masts with straight sails and a bowsprit. They were armed with 12-18 small-caliber cannons and were used for reconnaissance and messenger service as part of the skerry fleet of Peter I. Shnyava length 25-30 m, width 6-8 m, displacement about 150 tons, crew up to 80 people.

Schooner

A sea sailing vessel with a displacement of 100-800 tons, having 2 or more masts, is armed mainly with oblique sails. Schooners were used in sailing fleets as messenger ships. The schooners of the Russian fleet were armed with up to 16 guns.