Esperanto is an artificial language that unites the world. Esperanto - the language of international communication The language of Esperance

The city was inhabited by Belarusians, Poles, Russians, Jews, Germans, Lithuanians. People of different nationalities often treated each other with suspicion and even hostility. From his early youth, Zamenhof dreamed of giving people a common, understandable language in order to overcome alienation between peoples. He dedicated his whole life to this idea. While studying languages at the gymnasium, he realized that in any national language there are too many complexities and exceptions that make it difficult to master. In addition, the use as a common language of any one people would give unjustified advantages to this people, infringing on the interests of others.

Zamenhof worked on his project for more than ten years. In 1878, fellow high school students were already enthusiastically singing in the new language “Let the enmity of the peoples fall, the time has come!”. But Zamenhof's father, who worked as a censor, burned his son's work, suspecting something unreliable. He wanted his son to finish university better.

In the alphabet, letters are called like this: consonants - consonant + o, vowels - just a vowel:

- A - a

- B-bo

- C - co

Each letter corresponds to one sound (phonemic letter). The reading of a letter does not depend on the position in the word (in particular, voiced consonants at the end of a word are not stunned, unstressed vowels are not reduced).

The stress in words always falls on the penultimate syllable.

The pronunciation of many letters can be assumed without special training (M, N, K, etc.), the pronunciation of others must be remembered:

- C( co) is pronounced like Russian c: centro, sceno[scene] caro[tsʹro] "king".

- Ĉ ( Geo) is pronounced like Russian h: Cefo"chief", "head"; Ecocolado.

- G( go) is always read as G: groupo, geography[geography].

- Ĝ ( ĝo) - affricate, pronounced as a continuous jj. It does not have an exact match in Russian, but it can be heard in the phrase “daughter would”: due to the voiced b coming after, h pronounced and pronounced like jj. Cardeno[giardeno] - garden, etaco[etajo] "floor".

- H( ho) is pronounced as a dull overtone (eng. h): horizonto, sometimes as Ukrainian or Belarusian "g".

- Ĥ ( eo) is pronounced like Russian x: ameleono, ĥirurgo, aolero.

- J( jo) - as Russian th: jaguaro, jam"already".

- Ĵ ( o) - Russian well: argono, galuzo"jealousy", ĵurnalisto.

- L( lo) - neutral l(the wide boundaries of this phoneme make it possible to pronounce it like the Russian “soft l”).

- Ŝ ( So) - Russian w: ŝi- she, ŝablono.

- Ŭ ( ŭo) - short y corresponding to English w, Belarusian ў and modern Polish ł; in Russian it is heard in the words "pause", "howitzer": pazo[paўzo], Europo[europo] "Europe". This letter is a semivowel, does not form a syllable, occurs almost exclusively in the combinations "eŭ" and "aŭ".

Most Internet sites (including the Esperanto section of Wikipedia) automatically convert characters with x's typed in postpositions (x is not included in the Esperanto alphabet and can be considered as a service character) into characters with diacritics (for example, from the combination jx it turns out ĵ ). Similar typing systems with diacritics (two consecutively pressed keys type one character) exist in keyboard layouts for other languages as well—for example, in the "Canadian multilingual" layout for typing French diacritics.

You can also use the Alt key and numbers (on the numeric keypad). First, write the corresponding letter (for example, C for Ĉ), then press the Alt key and type 770, and a circumflex appears above the letter. If you dial 774, then the sign for ŭ will appear.

The letter can also be used as a substitute for diacritics. h in post-position (this method is an “official” replacement for diacritics in cases where its use is not possible, since it is presented in the Fundamentals of Esperanto: “ Printing houses that do not have the letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ may initially use ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, u”), however, this method makes the spelling non-phonemic and makes automatic sorting and transcoding difficult. With the spread of Unicode, this method (as well as others, such as diacritics in postposition - g’o, g^o and the like) is less and less common in Esperanto texts.

Vocabulary

| Swadesh list for Esperanto | ||

| № | Esperanto | Russian |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | mi | I |

| 2 | ci(vi) | you |

| 3 | li | is he |

| 4 | ni | we |

| 5 | vi | you |

| 6 | or | they |

| 7 | tiu cei | this, this, this |

| 8 | tiu | that, that, that |

| 9 | tie ci | here |

| 10 | tie | there |

| 11 | kiu | who |

| 12 | kio | what |

| 13 | kie | where |

| 14 | kiam | when |

| 15 | kiel | how |

| 16 | ne | not |

| 17 | ĉio, ĉiuj | everything, everything |

| 18 | multaj, pluraj | many |

| 19 | kelkaj, kelke | several |

| 20 | nemultaj, nepluraj | few |

| 21 | alia | other, different |

| 22 | unu | one |

| 23 | du | two |

| 24 | tri | three |

| 25 | kvar | four |

| 26 | kvin | five |

| 27 | granda | big, great |

| 28 | longa | long, long |

| 29 | larĝa | wide |

| 30 | dika | fat |

| 31 | peza | heavy |

| 32 | malgranda | little |

| 33 | mallonga (kurta) | short, brief |

| 34 | mallara | narrow |

| 35 | maldika | thin |

| 36 | virino | female |

| 37 | viro | Man |

| 38 | homo | human |

| 39 | infanto | child, child |

| 40 | edzino | wife |

| 41 | edzo | husband |

| 42 | patrino | mother |

| 43 | patro | father |

| 44 | besto | beast, animal |

| 45 | fiŝo | a fish |

| 46 | birdo | bird, bird |

| 47 | hundo | dog, dog |

| 48 | pediko | louse |

| 49 | serpento | snake, bastard |

| 50 | vermo | worm |

| 51 | arbo | wood |

| 52 | arbaro | Forest |

| 53 | bastono | stick, rod |

| 54 | frukto | fruit, fruit |

| 55 | semo | seed, seeds |

| 56 | folio | sheet |

| 57 | radiko | root |

| 58 | ŝelo | bark |

| 59 | floro | flower |

| 60 | herbo | grass |

| 61 | ŝnuro | rope |

| 62 | hato | skin, hide |

| 63 | viando | meat |

| 64 | sango | blood |

| 65 | osto | bone |

| 66 | graso | fat |

| 67 | ovo | egg |

| 68 | Korno | horn |

| 69 | vosto | tail |

| 70 | plumo | feather |

| 71 | haroj | hair |

| 72 | capo | head |

| 73 | orelo | ear |

| 74 | okulo | eye, eye |

| 75 | nazo | nose |

| 76 | buso | mouth, mouth |

| 77 | Dento | tooth |

| 78 | lango | tongue) |

| 79 | ungo | nail |

| 80 | piedo | foot, leg |

| 81 | gambo | leg |

| 82 | Genuo | knee |

| 83 | mano | hand, palm |

| 84 | flugilo | wing |

| 85 | ventro | belly, belly |

| 86 | tripo | entrails, intestines |

| 87 | goreo | throat, neck |

| 88 | dorso | back (backbone) |

| 89 | brusto | breast |

| 90 | koro | a heart |

| 91 | hepato | liver |

| 92 | trinki | drink |

| 93 | mani | eat, eat |

| 94 | Mordi | gnaw, bite |

| 95 | sucei | suck |

| 96 | kraĉi | spit |

| 97 | vomi | tear, vomit |

| 98 | blovi | blow |

| 99 | spirit | breathe |

| 100 | ridi | laugh |

Most of the vocabulary consists of Romance and Germanic roots, as well as internationalisms of Latin and Greek origin. There are a small number of stems borrowed from or through the Slavic (Russian and Polish) languages. Borrowed words are adapted to Esperanto phonology and written in the phonemic alphabet (that is, the original spelling of the source language is not preserved).

- Borrowings from French: When borrowing from French, regular sound changes occurred in most stems (for example, /sh/ became /h/). Many Esperanto verb stems are taken from French ( iri"go", macei"chew", marŝi"step", kuri"run" promeni"walk", etc.).

- Borrowings from English: at the time of the founding of Esperanto as an international project, the English language did not have its current distribution, so the English vocabulary is rather poorly represented in the main vocabulary of Esperanto ( fajro"Fire", birdo"bird", jes"yes" and some other words). Recently, however, several international anglicisms have entered the Esperanto vocabulary, such as bajto"byte" (but also "bitoko", literally "bit-eight"), blogo"blog", default"default", managerero"manager", etc.

- Borrowings from German: the main vocabulary of Esperanto includes such German stems as Nur"only", danko"gratitude", ŝlosi"lock up" morgatu"tomorrow", tago"day", jaro"year", etc.

- Borrowings from Slavic languages: barakti"flounder", klopodi"to bother" kartavi"burr", krom"except", etc. See below in the section "Influence of the Slavic languages".

On the whole, the Esperanto lexical system manifests itself as autonomous, reluctant to borrow new foundations. For new concepts, a new word is usually created from elements already existing in the language, which is facilitated by the rich possibilities of word formation. A vivid illustration here can be a comparison with the Russian language:

- English site, rus. website, esp. pacaro;

- English printer, rus. a printer, esp. printilo;

- English browser, rus. browser, esp. retumilo, krozilo;

- English internet, rus. the Internet, esp. interreto.

This feature of the language allows you to minimize the number of roots and affixes needed to master Esperanto.

In colloquial Esperanto, there is a tendency to replace words of Latin origin with words formed from Esperanto roots in a descriptive manner (flood - altakvaĵo instead of vocabulary inundo, extra - troa instead of vocabulary superflua, as in the proverb la tria estas troa - third wheel etc.).

In Russian, the most famous are the Esperanto-Russian and Russian-Esperanto dictionaries compiled by the famous Caucasian linguist E. A. Bokarev, and later dictionaries based on it. A large Esperanto-Russian dictionary was prepared in St. Petersburg by Boris Kondratiev and is available on the Internet. There are laid out [ when?] working materials of the Large Russian-Esperanto Dictionary, which is currently being worked on. There is also a project to develop and maintain a version of the dictionary for mobile devices.

Grammar

Verb

There are three tenses in the indicative mood in the Esperanto verb system:

- past (formant -is): mi iris"I walked" li iris"he was walking";

- the present ( -as): mi iras"I'm going" li iras"he's coming";

- future ( -os): mi iros"I will go, I will go" li iros"He will go, he will go."

In the conditional mood, the verb has only one form ( miirus"I would go"). The imperative mood is formed using the formant -u: iru! "go!" According to the same paradigm, the verb "to be" is conjugated ( esti), which even in some artificial languages is “incorrect” (in general, the conjugation paradigm in Esperanto knows no exceptions).

Cases

There are only two cases in the case system: nominative (nominative) and accusative (accusative). The rest of the relationships are conveyed using a rich system of prepositions with a fixed meaning. The nominative case is not marked with a special ending ( vilagio"village"), an indicator of the accusative case is the ending -n (vilacon"village").

The accusative case (as in Russian) is also used to indicate the direction: en vilaco"in the village", en vilaco n "to the village"; post krado"behind bars", post krado n "behind bars".

Numbers

There are two numbers in Esperanto: singular and plural. The only one not marked infanto- child), and the plural is marked with the multiplicity indicator -j: infanoj - children. The same for adjectives - beautiful - bela, beautiful - belaj. When using the accusative case with the plural at the same time, the plural indicator is placed at the beginning: “beautiful children” - bela jn infanto jn.

Genus

There is no grammatical category of gender in Esperanto. There are pronouns li - he, ŝi - she, ĝi - it (for inanimate nouns, as well as animals in cases where the gender is unknown or unimportant).

Communions

Regarding the Slavic influence at the phonological level, it can be said that there is not a single phoneme in Esperanto that would not exist in Russian or Polish. The Esperanto alphabet resembles the Czech, Slovak, Croatian, Slovene alphabets (there are no symbols q, w, x, characters with diacritics are actively used: ĉ , ĝ , ĥ , ĵ , ŝ And ŭ ).

In vocabulary, with the exception of words denoting purely Slavic realities ( bareo"borscht", etc.), out of 2612 roots presented in "Universala Vortaro" (), only 29 could be borrowed from Russian or Polish. Explicit Russian borrowings are banto, barakti, gladi, kartavi, krom(except), kruta, nepre(of course) rights, vosto(tail) and some others. However, the Slavic influence in vocabulary is manifested in the active use of prepositions as prefixes with a change in meaning (for example, sub"under", aceti"buy" - subaceti"bribe"; aŭskulti"listen" - subatskulti"eavesdrop"). The doubling of the stems is identical to that in Russian: plena-plena cf. "full-full" finfine cf. "eventually". Some Slavicisms of the first years of Esperanto were leveled over time: for example, the verb elrigardi(el-rigard-i) "look" replaced with new - aspect.

In the syntax of some prepositions and conjunctions, the Slavic influence is preserved, which was once even greater ( kvankam teorie… sed en la praktiko…“although in theory… but in practice…”). According to the Slavic model, the coordination of times is also carried out ( Li dir is ke li jam far is tion"He said he already did it" Li dir is, ke li est os tie"He said he would be there."

It can be said that the influence of the Slavic languages (and especially Russian) on Esperanto is much stronger than is commonly believed, and exceeds the influence of the Romance and Germanic languages. Modern Esperanto, after the "Russian" and "French" periods, entered the so-called. the “international” period, when individual ethnic languages no longer have a serious influence on its further development.

Literature on the subject:

carriers

It is difficult to say how many people speak Esperanto today. The well-known site Ethnologue.com estimates the number of Esperanto speakers at 2 million people, and according to the site, for 200-2000 people the language is native (usually these are children from international marriages, where Esperanto serves as the language of intra-family communication). This number was obtained by the American Esperantist Sidney Culbert, who, however, did not disclose the method of obtaining it. Markus Sikoszek found it grossly exaggerated. In his opinion, if there were about a million Esperantists in the world, then in his city, Cologne, there should be at least 180 Esperantists. However, Sikoszek found only 30 Esperanto speakers in that city, and an equally small number of Esperanto speakers in other major cities. He also noted that only 20 thousand people are members of various Esperanto organizations around the world.

According to the Finnish linguist J. Lindstedt, an expert on Esperanto "from birth", for about 1000 people around the world Esperanto is their native language, about 10 thousand more people can speak it fluently, and about 100 thousand can actively use it.

Distribution by country

Most Esperanto speakers live in the European Union, where most Esperanto events take place. Outside of Europe, there is an active Esperanto movement in Brazil, Vietnam, Iran, China, USA, Japan and some other countries. There are practically no Esperantists in Arabic countries and, for example, in Thailand. Since the 1990s, there has been a steady increase in the number of Esperanto speakers in Africa, especially in countries such as Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zimbabwe and Togo. Hundreds of Esperantists have appeared in Nepal, Philippines, Indonesia, Mongolia and other Asian states.

The World Esperanto Association (UEA) has the largest number of individual members in Brazil, Germany, France, Japan, and the United States, which may be indicative of the activity of Esperanto speakers by country, although it reflects other factors (such as the higher standard of living that allows Esperanto speakers in these countries to pay an annual fee).

Many Esperantists choose not to register with local or international organizations, making it difficult to estimate the total number of speakers.

Practical use

Hundreds of new translated and original books in Esperanto are published each year. Esperanto publishing houses exist in Russia, the Czech Republic, Italy, the United States, Belgium, the Netherlands and other countries. In Russia, at present, the Impeto (Moscow) and Sezonoj (Kaliningrad) publishing houses specialize in publishing literature in and about Esperanto, and literature is periodically published in non-specialized publishing houses. The organ of the Russian Union of Esperantists "Rusia Esperanto-Gazeto" (Russian Esperanto newspaper), the monthly independent magazine "La Ondo de Esperanto" (Esperanto Wave) and a number of less significant publications are published. Among online bookstores, the website of the World Esperanto Organization is the most popular, in the catalog of which in 2010 6510 different products were presented, including 5881 titles of book publications (not counting 1385 second-hand publications) .

The famous science fiction writer Harry Harrison himself spoke Esperanto and actively promoted it in his works. In the future world he describes, the inhabitants of the Galaxy speak mainly Esperanto.

There are also about 250 newspapers and magazines published in Esperanto , and many previously published issues can be downloaded free of charge on a specialized website . Most of the publications are devoted to the activities of the Esperanto organizations that issue them (including special ones - nature lovers, railway workers, nudists, Catholics, gays, etc.). However, there are also socio-political publications (Monato, Sennaciulo, etc.), literary ones (Beletra almanako, Literatura Foiro, etc.).

There is Internet TV in Esperanto. In some cases, we are talking about continuous broadcasting, in others - about a series of videos that the user can select and view. The Esperanto group regularly uploads new videos on YouTube. Since the 1950s, feature films and documentaries in Esperanto have appeared, as well as Esperanto subtitles for many films in national languages. The Brazilian studio Imagu-Filmo has already released two feature films in Esperanto - "Gerda malaperis" and "La Patro".

Several radio stations broadcast in Esperanto: China Radio International (CRI), Radio Havano Kubo, Vatican Radio, Parolu, mondo! (Brazil) and Polish Radio (since 2009 - as an Internet podcast), 3ZZZ (Australia).

In Esperanto, you can read the news, check the weather around the world, get acquainted with the latest in the field of computer technology, choose a hotel in Rotterdam, Rimini and other cities via the Internet, learn to play poker or play various games via the Internet. The International Academy of Sciences in San Marino uses Esperanto as one of its working languages, and it is possible to complete a master's or bachelor's degree using Esperanto. In the Polish city of Bydgoszcz, an educational institution has been operating since 1996, which trains specialists in the field of culture and tourism, and teaching is conducted in Esperanto.

The potential of Esperanto is also used for international business purposes, greatly facilitating communication between its participants. Examples include an Italian coffee supplier and a number of other companies. Since 1985, the International Commercial and Economic Group of the World Esperanto Organization has been active.

With the advent of new Internet technologies such as podcasting, many Esperanto speakers have been able to broadcast themselves on the Internet. One of the most popular Esperanto podcasts is Radio Verda (Green Radio), which has been broadcasting regularly since 1998. Another popular podcast, Radio Esperanto, is being recorded in Kaliningrad (19 episodes per year, 907 plays per episode on average). Esperanto podcasts from other countries are popular: Varsovia Vento from Poland, La NASKa Podkasto from the USA, Radio Aktiva from Uruguay.

Many songs are created in Esperanto, there are musical groups that sing in Esperanto (for example, the Finnish rock band "Dolchamar"). Since 1990, the company Vinilkosmo has been operating, releasing music albums in Esperanto in a variety of styles: from pop music to hard rock and rap. The online project Vikio-kantaro had over 1,000 lyrics in early 2010 and continued to grow. Dozens of video clips of Esperanto performers have been filmed.

There are a number of computer programs specifically written for Esperanto speakers. Many well-known programs have versions for the Esperanto-office application OpenOffice.org, the Mozilla Firefox browser, the SeaMonkey software package and others. The popular search engine Google also has an Esperanto version that allows you to search for information in both Esperanto and other languages. As of February 22, 2012, Esperanto has become the 64th language supported by Google Translate.

Esperantists are open to international and intercultural contacts. Many of them travel to attend conventions and festivals where Esperanto speakers meet old friends and make new ones. Many Esperantists have correspondents around the world and are often willing to host a traveling Esperantist for a few days. The German city of Herzberg (Harz) since 2006 has an official prefix to the name - "Esperanto city". Many signs, signboards and information stands here are bilingual - German and Esperanto. Esperanto blogs exist on many well-known services, especially many (more than 2000) on Ipernity. The famous Internet game Second Life has an Esperanto community that meets regularly at the Esperanto-Lando and Verda Babilejo sites. Esperanto writers and activists perform here, and there are linguistic courses. The popularity of specialized sites that help Esperanto speakers find: a life partner, friends, a job is growing.

Esperanto is the most successful of all artificial languages in terms of distribution and number of users. In 2004, members of the Universala Esperanto-Asocio (World Esperanto Association, UEA) consisted of Esperantists from 114 countries of the world, and the annual Universala Kongreso (World Congress) of Esperantists usually gathers from one and a half to five thousand participants (2209 in Florence in 2006, 1901 in Yokohama in th, about 2000 in Bialystok in th) .

Modifications and descendants

Despite its easy grammar, some features of the Esperanto language have attracted criticism. Throughout the history of Esperanto, people appeared among its supporters who wanted to change the language for the better, in their understanding, side. But since the Fundamento de Esperanto already existed by that time, it was impossible to reform Esperanto - only to create on its basis new planned languages that differed from Esperanto. Such languages are called in interlinguistics Esperantoids(Esperantides). Several dozen such projects are described in the Esperanto Wikipedia: eo:Esperantidoj .

The most notable branch of descendant language projects traces its history back to 1907, when the Ido language was created. The creation of the language gave rise to a split in the Esperanto movement: some of the former Esperantists switched to Ido. However, most Esperanto speakers remained true to their language.

However, Ido itself fell into a similar situation in 1928 after the appearance of an “improved Ido” - the Novial language.

Less noticeable branches are the Neo, Esperantido and other languages, which are currently practically not used in live communication. Esperanto-inspired language projects continue to emerge today.

Problems and prospects of Esperanto

historical background

Postcard with text in Russian and Esperanto, published in 1946

The political upheavals of the 20th century, primarily the creation, development and subsequent collapse of communist regimes in the USSR and the countries of Eastern Europe, the establishment of the Nazi regime in Germany, the events of the Second World War, played a major role in the position of Esperanto in society.

The development of the Internet greatly facilitated communication between Esperanto speakers, simplified access to literature, music and films in this language, and contributed to the development of distance learning.

Esperanto problems

The main problems that Esperanto faces are typical of most dispersed communities that do not receive financial assistance from government agencies. The relatively modest funds of Esperanto organizations, which consist mainly of donations, interest on bank deposits, as well as income from certain commercial enterprises (shareholdings, leasing real estate, etc.), do not allow for a wide advertising campaign, informing the public about Esperanto and its possibilities. As a result, even many Europeans do not know about the existence of this language, or rely on inaccurate information, including negative myths. In turn, the relatively small number of Esperanto speakers contributes to the strengthening of ideas about this language as an unsuccessful project that has failed.

The relative small number and dispersed residence of Esperanto speakers determine the relatively small circulation of periodicals and books in this language. The Esperanto magazine, the official organ of the World Esperanto Association (5500 copies) and the socio-political magazine Monato (1900 copies) have the largest circulation. Most Esperanto periodicals are rather modestly designed. At the same time, a number of magazines - such as "La Ondo de Esperanto" , "Beletra almanako" - are distinguished by a high level of printing performance, not inferior to the best national samples. Since the 2000s, many publications have also been distributed in the form of electronic versions - cheaper, faster and more colorfully designed. Some publications are distributed only in this way, including for free (for example, published in Australia "Mirmekobo").

Esperanto book circulations, with rare exceptions, are small, works of art rarely come out with a circulation of more than 200-300 copies, and therefore their authors cannot professionally engage in literary work (in any case, only in Esperanto). In addition, for the vast majority of Esperantists, this language is the second, and the degree of proficiency in it does not always allow one to freely perceive or create complex texts - artistic, scientific, etc.

There are known examples of how works originally created in one national language were translated into another through Esperanto.

Esperanto perspectives

In the Esperanto community, the idea of introducing Esperanto as an auxiliary language of the European Union is especially popular. Proponents of such a decision believe that this will make interlingual communication in Europe more efficient and equal, while solving the problem of European identification. Proposals for a more serious consideration of Esperanto at the European level were made by some European politicians and entire parties, in particular, representatives of the Transnational Radical Party. In addition, there are examples of the use of Esperanto in European politics (for example, the Esperanto version of Le Monde Diplomatic and the newsletter "Conspectus rerum latinus" during the Finnish EU Presidency). A small political party "Europe - Democracy - Esperanto" is participating in elections at the European level, which received 41,000 votes in the 2009 European Parliament elections.

Esperanto enjoys the support of a number of influential international organizations. A special place among them is occupied by UNESCO, which adopted in 1954 the so-called resolution of Montevideo, which expresses support for Esperanto, the goals of which coincide with the goals of this organization, and UN member countries are called for the introduction of teaching Esperanto in secondary and higher educational institutions. UNESCO also adopted a resolution in support of Esperanto in . In August 2009, the President of Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, expressed his support for Esperanto in his letter and the hope that in time it will be accepted by the world community as a convenient means of communication that does not grant privileges to any of its participants.

As of December 18, 2012, the Esperanto section of Wikipedia contains 173,472 articles (27th place) - more than, for example, sections in Slovak, Bulgarian or Hebrew.

Esperanto and religion

The phenomenon of Esperanto has not been ignored by many religions, both traditional and new. All major sacred books have been translated into Esperanto. The Bible was translated by L. Zamenhof himself (La Sankta Biblio. Londono. ISBN 0-564-00138-4). Published translation of the Koran - La Nobla Korano. Kopenhago 1970. On Buddhism, La Instruoj de Budho. Tokyo. 1983. ISBN 4-89237-029-0. Vatican Radio broadcasts in Esperanto, the International Catholic Association of Esperantists has been active since 1910, and since 1990 a document Norme per la celebrazione della Messa in Esperanto The Holy See has officially authorized the use of Esperanto during worship, the only planned language. On August 14, 1991, Pope John Paul II spoke to more than a million young listeners in Esperanto for the first time. In 1993 he sent his apostolic blessing to the 78th World Esperanto Congress. Since 1994, the Pope of Rome, congratulating Catholics around the world on Easter and Christmas, among other languages, addresses the flock in Esperanto. His successor Benedict XVI continued this tradition.

The Baha'i Faith calls for the use of an auxiliary international language. Some Baha'i followers believe that Esperanto has great potential for this role. Lydia Zamenhof, the youngest daughter of the creator of Esperanto, was a follower of the Baha'i faith and translated into Esperanto the most important works of Baha'u'llah and 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

The main oomoto-kyo theses is the slogan "Unu Dio, Unu Mondo, Unu Interlingvo" ("One God, One World, One Language of Communication"). Esperanto creator Ludwig Zamenhof is considered a kami saint in oomoto. Esperanto was introduced as an official language in oomoto by its co-creator Onisaburo Deguchi. Won Buddhism is a new branch of Buddhism that emerged in South Korea, actively uses Esperanto, participates in international Esperanto sessions, the main sacred texts of Won Buddhism have been translated into Esperanto. Esperanto is also actively used by the Christian spiritualist movement "Goodwill League" and a number of others.

perpetuation

Esperanto-related names of streets, parks, monuments, plaques and other objects are found all over the world. In Russia it is.

Image copyright Jose Luis Penarredonda

Esperanto was spoken by a fairly small number of people during the century of its existence. But today, this unique language invented by a Polish doctor is experiencing a real revival. Why did people start learning a language without having ingnationality and long history?

In a small house in north London, six young people enthusiastically attend language lessons every week. It has been studied for 130 years - a tradition that has survived wars and chaos, neglect and oblivion, Hitler and Stalin.

They do not practice this language in order to travel to another country. He will not help them find a job or explain themselves in a store abroad.

Most of them communicate in this language only once a week in these classes.

However, this is an absolutely full-fledged language in which they write poetry or swear.

Although it first appeared in a small booklet written by Ludwik L. Zamenhof in 1887, it became the most developed and most popular artificial language ever created.

And yet many will tell you that Esperanto is a failure. More than a century after its creation, no more than two million people speak this language - only some too extravagant hobby can have such a number of supporters.

But why is the number of Esperanto speakers on the rise today?

From the League of Nations to Speakers' Corner

Esperanto was supposed to be the only language of international communication, the second after the native one for every person in the world. That is why it is quite easy to learn. All words and sentences are built according to clear rules, of which there are 16 in total.

Esperanto does not have the confusing exceptions and grammatical forms of other languages, and its vocabulary is borrowed from English, German, and several Romance languages such as French, Spanish, or Italian.

Esperanto was to be the language of the future. It was introduced at the International Exhibition in 1900 in Paris, and soon the French intelligentsia became fascinated with the language, which considered it a manifestation of the modernist desire to improve the world through rationality and science.

The strict rules and clear logic of this language corresponded to the modern worldview. Esperanto seemed to be a more perfect communication tool than "natural" languages, full of illogicalities and oddities.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption French children learn Esperanto

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption French children learn Esperanto

Initially, great hopes were placed on Esperanto.

In the first language textbook, Zamenhof argued that if everyone spoke the same language, "education, ideals, convictions and goals would be common, and all peoples would be united in a single brotherhood."

The language was to be called simply lingvo internacia, that is, the international language.

However, Zamenhof's pseudonym "Doctor Esperanto" - "doctor who hopes" - turned out to be more accurate.

The colors of the official flag of the language - green and white - symbolize hope and peace, and the emblem - a five-pointed star - corresponds to the five continents.

The idea of a common language that would unite the world resonated in Europe. Some of Esperanto's supporters have held important government positions in several countries, and Zamenhof himself has been nominated 14 times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

There was even an attempt to create a country whose inhabitants would speak Esperanto.

The state of Amikeho was founded on a small territory of 3.5 square meters. km between the Netherlands, Germany and France, which throughout history has been a kind of "no man's land".

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Esperantists have been meeting in clubs since the early days of the language.

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Esperantists have been meeting in clubs since the early days of the language.

Soon the lean, bearded ophthalmologist became something of a patron saint of Esperantia, the "nation" of Esperanto speakers.

At recent congresses, participants staged processions with portraits of the doctor, not too different from the religious marches of Catholics on Good Friday.

Numerous statues and plaques around the world have been erected in honor of Dr. Zamenhof, streets, an asteroid and a species of lichen bear his name.

In Japan, there is even a religious sect Oomoto, its members promote communication in Esperanto and honor Zamenhof as one of their deities.

Even when the First World War put aside the idea of creating Amikejo and the dreams of world peace became too illusory, the Esperanto language continued to flourish.

It could have become the official language of the newly created League of Nations if France had not voted against it.

But the Second World War put an end to the heyday of Esperanto.

Both dictators, Stalin and Hitler, began persecuting Esperantists. The first - because he saw Esperanto as an instrument of Zionism, the second did not like the anti-nationalist ideals of the community.

Esperanto was spoken in Nazi concentration camps - Zamenhof's children died in Treblinka, Soviet Esperantists were sent to the Gulag.

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Esperantists have always been pacifists and fought against fascism

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Esperantists have always been pacifists and fought against fascism

But those who managed to survive began to unite again, although the post-war community was very small and not taken seriously.

In 1947, shortly after the Youth Congress in England, George Soros spoke at London's famous Speakers' Corner.

As a teenager, he delivered a gospel sermon in Esperanto at a traditional gathering place for conspiracy theorists and marginal activists.

Perhaps he did this in youthful fervor, as the future billionaire soon left the community.

Birth of a community

The study of Esperanto was mostly self-paced. Esperantists pored over the textbook alone, figuring out grammar rules and memorizing words on their own. There was no teacher to correct the mistake or improve the pronunciation.

This is exactly how one of the most famous Esperantists in the world, Anna Levenshtein, studied the language as a teenager.

The girl was annoyed by the French she learned at school, due to the many exceptions and difficult grammar, and one day she noticed the address of the British Esperanto Association printed at the end of the textbook.

She sent a letter, and soon she was invited to a meeting of young Esperantists in St. Albans, north of London.

The girl was very worried, because it was her first independent trip outside the city.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption The first Esperanto textbooks

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption The first Esperanto textbooks

“I understood everything that others said, but I didn’t dare to talk myself,” she recalls. The meeting was mostly young people in their early twenties.

The trip to St Albans was a turning point in her life. Esperanto was a puzzle that Loewenstein solved on her own, but now she could share her experience with the whole world.

She gradually gained confidence in the language and soon joined the Esperanto group that was gathering in north London.

The need to get there by three buses did not cool her ardor.

The global community that Loewenstein joined was formed through mail correspondence, the publication of paper magazines, and annual conventions.

Abandoning the big politics and global ambitions of the past, Esperantists have created a culture whose goal is simply "to connect people with a common passion," explains Angela Teller, who speaks Esperanto and researches the language.

People met at conferences and made friends. Some fell in love and got married, and children in such families spoke Esperanto from birth.

New generations don't need as much patience as their parents. Now Esperanto lovers can communicate in the language online every day.

Communication services since the dawn of the Internet, such as Usenet, had chat rooms and pages dedicated to Esperanto.

Today, the young Esperanto community actively uses social networks, primarily in the relevant Facebook and Telegram groups.

Of course, the Internet has become a very logical meeting place for a community scattered around the world.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Investor and philanthropist George Soros was taught Esperanto by his father

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Investor and philanthropist George Soros was taught Esperanto by his father

"The online space allows you to rethink old forms of communication in a new environment," explains Sarah Marino, lecturer in communication theory at Bournemouth University.

"Online communication is much faster, cheaper and more modern, but the idea itself is not new," she adds.

Today, Esperanto is one of the most widely spoken languages on the Internet (if you take into account the ratio of the number of native speakers of this language).

The Wikipedia page has about 240,000 articles, which practically puts Esperanto on a par with Turkish, which has 71 million speakers, or Korean (77 million speakers).

Popular Google and Facebook products have had Esperanto versions for many years, and there are also many online services for learning the language.

Exclusively for Esperanto speakers, there is a free housing exchange service - Pasporta Servo.

But the real revolution took place in the least expected place.

New platform

In 2011, Luis von Ahn, a scientist and entrepreneur from Guatemala, spoke about his new idea. Since he was the one who came up with CAPTCHA, the technology that helped digitize millions of books for free, his new project immediately aroused interest.

In his TEDx talk, he announced that he would translate the Internet by teaching foreign languages to users. The tool with which he was going to do this was called Duolingo.

This idea captured Esperantist Chuck Smith, the founder of the Esperanto Wikipedia and an active promoter of the spread of the language on the Internet.

Image copyright Alamy Image caption The German city of Herzberg am Harz has been named "City of Esperanto" since 2006.

Image copyright Alamy Image caption The German city of Herzberg am Harz has been named "City of Esperanto" since 2006.

Smith was convinced that Duolingo would grow into something great. He sent an email to von Ahn, an entrepreneur who had already sold two of his companies to Google and turned down a job with Bill Gates himself.

Von Ahn responded to the email the same day. He noted that Esperanto was considered but not a priority.

Then the Esperantists raised a fuss and convinced the creators of the Duolingo program that Esperanto should be included in the list of languages.

The first version of the Esperanto course for English users appeared on the Duolingo website in 2014, a little later the course was developed in Spanish and Portuguese, and now the English version is being updated.

Smith led a team of 10 people who worked 10 hours a week for eight months. None of them got paid for it, but they didn't complain - they were all enthusiastic about spreading Esperanto.

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Esperanto lesson in a Polish school

Image copyright Getty Images Image caption Esperanto lesson in a Polish school

Learning Esperanto is easy and fun on the Duolingo platform. You can complete one lesson per five-minute break or while commuting to work or home.

If you have abandoned your studies, the green owl will gently but persistently remind you to return to the site.

Duolingo has become the most effective tool for learning Esperanto in the history of the language.

As the program shows, about 1.1 million users have subscribed to an Esperanto course - almost half of all people who speak Esperanto in the world.

About 25% of people who started a course on Duolingo completed it, says a platform official.

However, live communication in the language still remains necessary. That is why Esperanto students come to language schools such as this one in north London where Anna Levenshtein teaches.

On the doors of the classroom is a green star, the emblem of Esperanto. The students are warmly welcomed by a domestic dog, they are also offered tea.

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Streets and squares all over the world bear the name of Dr. Zamenhof

Image copyright Alamy Image caption Streets and squares all over the world bear the name of Dr. Zamenhof

Along the walls of the cozy studio are shelves with the works of Marx, Engels, Rosa Luxemburg and Lenin. There are also several books in Esperanto, as well as "Utopia" by Thomas More in an orange cover.

The school is attended by very different people. Some, like James Draper, took up learning Esperanto for pragmatic reasons. Languages are not easy for him, and Esperanto is one of the easiest.

Other students, on the contrary, are stubborn polyglots who are interested in artificial language, which is a useful tool for understanding other languages.

The reasons may be very different, but all Esperantists have something in common. This is curiosity, openness to new experience and a benevolent attitude towards the world.

Angela Teller has known this since the day her children returned from the Esperanto camp. She asked them where their friends were from, and the children replied, "We don't know."

"Nationalities somehow receded into the background," she explains. "It seems to be the way it should be."

Esperanto is the best known and most widely used artificial language in the world. Like Volapuk, it appeared at the end of the 19th century, but this language was much more fortunate. Its creator is the doctor and linguist Lazar Markovich Zamenhof. Today Esperanto is spoken by 100 thousand to several million people, there are even people for whom the language is native (usually children from international marriages, in which Esperanto is the language of family communication). Unfortunately, exact statistics for artificial languages are not kept.

The first textbook and description of the language was published in Warsaw on July 26, 1887. The author took the pseudonym "Esperanto", the language itself at that moment was called simply and modestly: "international language". However, the author's pseudonym was instantly transferred to the language, and the language almost immediately gained great popularity: the Esperanto Academy was soon created, and in 1905 the first world congress of Esperanto took place.

The Latin alphabet was taken as the basis of the Esperanto alphabet. There are 28 letters in Esperanto, one letter corresponds to one sound (that is, how it is written is how it is heard - and vice versa). The stress always falls on the penultimate syllable.

The vocabulary of Esperanto was created on the basis of the Germanic and Romance languages, the language has many roots from Latin and Greek.

There are Esperanto dictionaries, for example, on the Internet you can find a large Esperanto-Russian dictionary, there are even plans to release Esperanto dictionaries for mobile devices.

Esperanto grammar is the dream of any student of a foreign language. There are only 16 rules in Esperanto. Everything.

There are two cases in the language, there is a plural and a singular, but there is no grammatical gender category (that is, there are, of course, pronouns he, she, it, but they do not require adjectives and verbs to agree with them).

Esperanto is the most widely spoken international planned language. Doctor Esperanto(from lat. Esperanto- hoping) is the pseudonym of Dr. Ludwig (Lazar) Zamenhof, who published the basics of the language in 1887. His intention was to create an easy-to-learn, neutral language for international understanding, which, however, should not replace other languages. At the initiative of Zamenhof, an international language community was created, using Esperanto for various purposes, primarily for travel, correspondence, international meetings and cultural exchange.

The international language of Esperanto makes it possible to have direct contact with people from more than 100 countries where Esperanto is spoken alongside their mother tongue. Esperanto is the link of the international language community. Daily meetings of representatives of a dozen nations: Hungarians, Belgians, Spaniards, Poles and even Japanese, who talk about their everyday problems and share their experiences, are a common thing. Everyday life of Esperanto is an Internet discussion between twenty countries: in Indigenaj Dialogoj(Dialogues of One Begotten) Indigenous people from different parts of the world regularly exchange information in Esperanto on the preservation of their culture and rights. Everyday life of Esperanto is when a poem by an Italian published by a Belgian publishing house, a review of which can be found in a Hungarian magazine, becomes a song performed by a Danish-Swedish group and then discussed on the Internet by Brazilians and Nigerians. The world is getting closer, Esperanto is bringing people together.

Thanks to its rich application possibilities, Esperanto gradually became a living language. New concepts quickly take root in it: a mobile phone - postelefono(lit. pocket phone, pronounced "posh-telephono"), laptop - tekokomputilo(computer in the briefcase), and the Internet - Interreto(Internet). Esperanto estas mia lingvo(Esperanto is my language)

A bridge language can be learned much faster than other languages. A school experiment showed that Esperanto requires only 20-30% of the time needed to master any other language at the same level. Many learners of Esperanto begin to use it in international communication after 20 lessons. This is possible due to the fact that, firstly, Esperanto, including pronunciation, has clear rules, and secondly, with an optimal word-formation system, the number of roots that need to be memorized is small. Therefore, even speakers of non-European languages find Esperanto much easier than, for example, English.

The grammar of this language is also built according to the rules, and the student quickly enough begins to confidently, and, most importantly, correctly, make sentences. A few years later, learners of Esperanto speak it as if they were their mother tongue. They actively participate in its preservation and contribute to its further development. This practically does not happen with other foreign languages: their study requires a lot of effort, and there are many exceptions to their rules.

Many of those who have mastered Esperanto also know other languages. Esperanto allows you to look at the world as a whole and arouses interest in other national cultures. Someone has learned a planned language after English and has the opportunity to communicate also with people from countries where the latter is not so popular. And someone after Esperanto began to study the languages of different countries, because thanks to this artificial language he learned about these countries and wanted to get more information.

Every year there are hundreds of international meetings on Esperanto issues, not only in Europe, but also in East Asia, Africa, for example in Togo and Nigeria, in South America. Guest service helps organize personal meetings Passport Servo and the Amikeca Reto Friendship Network. You can communicate in Esperanto every day without leaving your home. There are several million pages on the Internet in this language that unites peoples, and on forums, interlocutors from dozens of countries discuss a variety of topics.

Esperanto songs have been sung for more than a hundred years. Now they are released on CD by about twenty bands, some works can be downloaded from the Internet. Every year about two hundred books and several hundred magazines are published in Esperanto, with which mainly authors from different countries collaborate. For example, Monato magazine publishes articles on politics, economics and culture in about 40 countries. About 10 radio stations broadcast in Esperanto.

Esperanto allows you to take a step towards each other to talk somewhere in the middle. There is no Esperanto-speaking country on the world map. But those who know this language can make acquaintances all over the world.

See also information about Esperanto:

Nikolaeva Evgeniya

The paper tells about the most popular modern artificial language - Esperanto, which can rightfully claim to be the language of international communication.

Download:

Preview:

Municipal educational institution

secondary school No. 96

Abstract on the topic:

"Esperanto - the language of international communication"

I've done the work:

11 "A" class student

Nikolaeva Evgeniya

Work checked:

teacher of Russian language

and literature

Maslova Natalya Mikhailovna

2007 - 2008 academic year

Nizhny Novgorod

- Introduction.

- Esperanto and other artificial languages.

- From the history of Esperanto.

- Basic language facts:

- Alphabet and reading.

- A set of diacritics.

- Esperanto vocabulary.

- Flexible system of word formation.

- Grammar.

- The main areas of use of Esperanto.

- Esperanto speakers.

- Modifications and descendants.

- Problems and prospects of Esperanto.

- Conclusion.

List of used literature:

- Bokarev E.A. Esperanto - Russian dictionary. - M.: Russian language, 1982.

- Big encyclopedic dictionary "Linguistics". - M., 2004.

- Doug Goninaz. Slavic influence in Esperanto. // Problems of the international auxiliary language. - M .: "Nauka", 1991.

- Kolker B.G. The contribution of the Russian language to the formation and development of Esperanto: Abstract. - M., 1985.

- What is Esperanto? // Website www.esperanto.mv.ru.

- Esperanto - what it is, where to study. // Site esperanto.nm.ru.

- Language as the most important mechanism for promoting tolerance: Broadcast on Radio Liberty. - 17.08.2006.

Esperanto and other artificial languages

Interlinguistics- a section of linguistics that studies interlingual communication and international languages as a means of such communication.

The large encyclopedic dictionary "Linguistics" gives the following definition of artificial languages: "Constructed languages- sign systems created for use in areas where the use of natural language is less effective or impossible.

There are so-called "non-specialized general-purpose languages" or "international artificial languages". Any international artificial language is called planned if he received realization in communication; less implemented artificial languages are calledlinguistic projects. Only published linguistic projects by different researchers number up to 2 thousand or more (idioms - neutral (1893 - 1898), interlingua (1951), loglan, ro), while the number of planned languages does not exceed a dozen (Volapyuk, Ido (1907 ), Interlingua, Latin-Blue-Flexione, Novial (1928), Occidental, Esperanto (1887)) (according to other sources, about 600 artificial languages).

Human fantasy is unbridled. Tolkienists, of course, will remember Quenya, and fans of the endless Star Trek series - Klingon; programming languages, in essence, are artificial languages, there are also formalized scientific languages and information languages. The grammar of these languages is built on the example of ethnic languages; artificial languages and vocabulary (primarily international) are borrowed from ethnic languages.

Let's highlight the most popular and interesting of the above languages.

- The first known project was the language project called"universalglot", which was published in 1868 by the Frenchman Jean Pirro. First of all, this language had a simple morphology, systematized along the lines of the Romance and Germanic languages. Pirro himself said that when creating a universalglot, he, first of all, chose the most popular and easily pronounceable words from different living languages. The public, however, did not appreciate the efforts of the Frenchman and did not speak his language.

- In Quenya elves spoke. Of course, the elves did not exist in reality - and they themselves, and this language was invented by Professor J. R. R. Tolkien for Middle-earth, in which the events of the world-famous fantasy saga "The Lord of the Rings" unfolded. Naturally, the writer did this not from scratch, but took Latin as a basis, borrowing phonetics and spelling from Finnish and Greek. In general, according to the Professor, Quenya in the times described in the novel was about the same as Latin is for us, that is, a dead language; elves - contemporaries of the ring-bearer, the hobbit Frodo Baggins, already spoke a different dialect, but wrote everything down using the tengwar script.

Calligraphy in tengwara

- Specially for the American science fiction series "Star Trek" (Star Trek), professional linguist Mark Okrand invented the language Klingons (races of aliens). This language was created on the basis of the dialect of the American Indians Mutsun, the last of which died in the 30s of the last century. It is said that the US intelligence agencies used this rare language in radio communications so that the Russians would not understand.

Klingon

- Another artificial language saltresol. People who know the notes, for sure, guess that this is a language whose words are made up of seven syllables, and these syllables are nothing more than notes (do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-si). Solresol was invented by the Frenchman Jean-Francois Sudre in 1817 and was subsequently improved by other specialists. You can speak and write in this language as you like: even with colors, even with the names of notes, even with signal flags; you can play a musical instrument or communicate in the language of the deaf and dumb.

Solresol Recording Capabilities

This language did not become relatively popular, losing its positions, like other artificial languages, Esperanto.

- There are between 2 and 20 million people in the world who speak Esperanto - a language invented in 1887 not by a linguist, but by an oculist, Czech Ludwik Zamenhof. Esperanto, which was conceived by its creator as "auxiliary, the simplest and easiest international" language, is the result of ten years of work; named after the author's pseudonym. The Esperanto alphabet is built on the basis of Latin with the addition of some features, and new words are formed from elements already existing in the language.

Bible in Esperanto

Problems and prospects of Esperanto

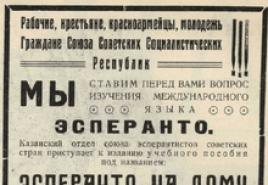

For Esperantists, the question of the prospects of the language is rather painful. At the beginning of the 20th century, the influence of Esperanto grew continuously; it was especially great inthe USSR in the 1920s, when this language, with the filingTrotsky has been widely studied as "the language of the world revolution". Esperanto was actively used in the network of "work correspondents" (work correspondents). At that time, even the inscriptions on postal envelopes were duplicated in two languages, Russian and Esperanto. However, already in the 1930s and 1940s, Esperanto speakers were subjected to repression: in the USSR - as "Trotskyists", "spies" and "terrorists", and in the territories controlled by Nazi Germany - as supporters of the "pro-Jewish" doctrine. In the USSR and Germany, the Esperanto movement actually ceased to exist.

In the 1950s, when Esperanto began to legalize again, the place of the de facto international language was taken byEnglish , in this regard, the growth in the number of Esperanto supporters is slower (for example, the number of individual members of the World Esperanto Association (UEA) even decreased from 8071 people in 1991 to 5657 in 2002, the fall in the number of associate members in 1991 - from 25 to 19 thousand - due to the crisis of the Esperanto movement in the socialist countries, especially in Bulgaria and Hungary, after the abolition of state support for local associations that were part of the UEA). In classical Esperanto organizations (the World Esperanto Association, the Russian Union of Esperantists and others) in recent years there has been an equalization in the number of members, and the number of people who learn and use Esperanto on the Internet and do not join any organizations is also increasing.

At present, most Esperanto periodicals look rather poor, including the illustrated social and political magazine Monato (one of the most popular).

Among the possible prospects for the use of Esperanto in the Esperanto community, the idea of introducing Esperanto as an auxiliary language is now especially popular.European Union . It is believed that such use of Esperanto would make interlingual communication in Europe more efficient and equal. Proposals for a more serious consideration of Esperanto at the European level have been made by some European politicians and entire parties, there are examples of the use of Esperanto in European politics (for example, the Esperanto versions of Le Monde Diplomatic and the newsletter "Conspectus rerum latinus" during the EU PresidencyFinland ).

"Europe needs a single language - an intermediary, lingua franca", - such a statement was made on the pages of the large daily newspaper "Sydsvenska Dagbladet" by the co-founder of the Swedish Green Party Per Garton, who proposes three candidates for the role of the intermediary language: Latin, Esperanto and French. According to the Swedish politician,« it will take only one or two generations for the political decision to introduce Latin or Esperanto to become a reality in the European Union». Garton considers the further spread of English as an international language as a threat to the independence and identity of the EU.

Recently, the number of new Esperantists has been growing especially actively thanks to the Internet. For example, a multilingual online resourcelernu! is the largest source of new Esperanto learners on the web.

Modifications and descendants

Despite its easy grammar, Esperanto has some drawbacks. Because of this, Esperanto had such supporters who wanted to change the language for the better, as they thought, side. But since by that time already existedFundamento de Esperanto , Esperanto was impossible to reform. Then the reformers found a solution: they created new planned languages that differed from Esperanto. The most noticeable branch of linguistic projects - descendants traces its history fromthe year the language was createdido . The creation of the language gave rise to a split in the Esperanto movement: some of the former Esperantists switched to Ido. However, most Esperanto speakers remained true to their language. However, in 1928, Ido itself fell into a similar situation after the appearance of an “improved Ido” - the languagenovial . Less visible branches are languagesedo And Esperantido , which differ from Esperanto only in a modified spelling. Until our time, all four languages have almost lost their supporters.

Esperanto speakers

It is difficult to say how many people speak Esperanto today. The most optimistic sources give estimates of up to 500 million people worldwide. The well-known site Ethnologue.com estimates the number of Esperanto speakers at 2 million people, and, according to the site, 2,000 people speak their native language (usually these are children from international marriages, where Esperanto serves as the language of intra-family communication).

There is no doubt that a really large number of educated people have at some time become familiar with Esperanto, although not all of them have become active users of it as a result. The prevalence of a language among educated people can be indirectly judged by the volume of Wikipedia in this language, which (as of May 2007) contains over 84,000 articles and ranks 15th in this indicator, significantly surpassing many national languages. Hundreds of new translations and originals are published each year.books in Esperanto, writtensongs and films are made. There are also many newspapers and magazines published in Esperanto; eatradio stations , broadcasting in Esperanto (for example,China Radio International (CRI) And Polish radio ). In November 2005, the first worldwide Internet television in Esperanto was launched.Internacia Televido (ITV).

In Russia, the publishing house "Impeto" (Moscow ) And " season" (Kaliningrad ), literature is periodically published in non-specialized publishing houses, an organ is publishedRussian Union of Esperantists « Rusia Esperanto-Gazeto» (Russian Esperanto - newspaper), monthly independent magazine "La Ondo de Esperanto» ("The Esperanto Wave") and a number of less significant publications.

With the advent of new Internet technologies such aspodcasting , many Esperantists got the opportunity to self-broadcast on the Internet. One ("Green Radio") which regularly broadcasts from of the year.

Most Esperantists are open to international and intercultural contacts. Many of them travel to attend conventions and festivals where Esperanto speakers meet old friends and make new ones. Many Esperantists have correspondents around the world and are often willing to host a traveling Esperantist for a few days. Visiting exchange network popular among Esperanto speakersPassport Servo .

famous science fiction writerHarry Harrison he speaks Esperanto himself and actively promotes it in his works. In the world of the future he describes, the inhabitants of the Galaxy speak mainly Esperanto. Esperanto is the most successful of all artificial languages.

Dominic Pellet has translated the well-known text editor Vim into Esperanto - he announced this in a mail group (programistoj - respondas), where Esperanto-speaking information technology specialists gather.

The Slovak publishing house Espero, which has been operating since 2003, plans to release a collection of Stan Marchek's crossword puzzles, a book of poems by Iranian poets, an electronic Esperanto-Slovak dictionary on a laser disc, and several more books and discs.

The publishing house of the Flemish Esperanto League (FEL) is preparing a translation of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species and several novels at once, includingThe Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas translated by Daniel Moiran.

In New York, the Mondial publishing house has already publishedEsperanto translation of "White on Black" by Gallego (Ruben Gallego, Laureate of Booker - 2003 , the author of the novel wrote a special preface to the Esperanto edition: “I thank all future Esperanto readers for the beautiful Esperanto language, for their attention to my work. Read. This is a good book. I hope, I really want to believe that bad books are not translated and written in the language of dreams, the language of hope - Esperanto"), is working on a 740-page tome entitled "Concise Encyclopedia of the Original Literature of Esperanto" ("A Concise Encyclopedia of the Original Literature of Esperanto"). Literature in Esperanto). The book promises to be the most comprehensive reference guide to non-translatable Esperanto literature.

Mikhail Bronstein published the novel Ten Days of Captain Postnikov,published by the Impeto publishing house in Russian translation Anatoly Radaev. The action of the novel takes place in 1910 - 1911 with excursions into the past and the future; scenes - Moscow, St. Petersburg and the steamer "George Washington", on which Alexander Postnikov, the protagonist of the novel, went to the 6th World Esperanto Congress in the USA. On the way to America, Postnikov talks a lot with Ludwik Markovich Zamenhof, the "initiator" of Esperanto - from such dialogues, the reader, among other things, learns a lot about the life of the creator of Esperanto himself.

It looks like 2008 will be rich in encyclopedias - a biographical guide about famous Esperantists is being prepared by the Kaliningrad publishing house "Sezonoj". There will also be translations by Jules Verne and Borges.

Main Uses of Esperanto

- Periodicals.

There are many periodicals published in Esperanto, among them there are about 10 known all over the world (“Esperanto”, “LaOndodeEsperanto”, “Monato”, “Kontakto”, “LaGazeto”, “Fonto”, “Literatura Foiro” and others). Most of the publications are organs of various Esperanto organizations (for example, “Esperanto” is the organ of the World Esperanto Association; “RusiaEsperanto-Gazeto” is a joint publication of the Russian Esperanto Union and the Russian Youth Esperanto Movement), but there are also “independent” publications: most the most famous of them is the Monato magazine: it publishes various materials in Esperanto, but never about Esperanto.

- Correspondence.

From the very first days of its existence, Esperanto served for international (primarily private) correspondence. Many people are attracted by the opportunity, having mastered one language, to acquire correspondents in various countries of the world.

- Internet .

The spread of the Internet has a beneficial effect on all dispersed language communities, including Esperanto speakers. Now it is possible to practice the language every day (and not only during international Esperanto meetings) in chat rooms, on news sites, in mail groups, forums and so on. There is an opinion, which is difficult to confirm or refute, that Esperanto ranks second on the Web in terms of the volume of use for interlingual communication. There are distance courses for teaching Esperanto via the Internet, many people communicate in Esperanto on the Web for several years, while not having the experience of oral communication.

- Esperanto meetings.

Various kinds of congresses, summer camps, festivals and so on. Since the first mass congress in Boulogne - sur - Mayor, this area of use of Esperanto has been very popular. Meetings are mass (World Esperanto Congress, IJK, RET and others) and specialized (Congress of Railway Workers, Meeting of Cat Lovers, Table Tennis Championship and the like).

- Use in international families.

There are about a thousand international families in which the main language of family communication is Esperanto. According to the websitewww.ethnologue.com up to 2 thousand people are considered native speakers (denaskaj parolantoj) of Esperanto (these are not necessarily the children of international marriages, there are about many children in Russia who know Esperanto as their native language with both Russian parents).

- aesthetic function.

Contrary to expectations, almost since its inception, Esperanto has been used to write original fiction (both prose and poetry). In 1993, an Esperanto section was formed in the international organization of writers PEN. The first Esperanto novel, Kastelode Prelongo, was published as early as 1907. Esperanto phraseology, "catch phrases" and idioms in this language have become a popular topic for Esperanto studies.

- The science .

Esperanto is the working language of the International Academy of San Marino (AIS). In a number of Eastern European countries (including Russia and Estonia) there are universities where students are required to study Esperanto in the first or second year, and the thesis must be accompanied by a brief annotation in IL (InternaciaLingvo), as Esperanto is often called in AIS . The Esperanto Academy publishes “AkademiajStudoj”, collections of articles are published in Germany, France and other countries. Since the 1920s, a lot of work has been done to develop terminology, dozens of terminological dictionaries (general and special: in chemistry, physics, medicine, law, railways and other sciences) have been published.

- Propaedeutics.

Esperanto is taught in a number of schools around the world as the first language before learning an ethnic language (more often French or Italian). The experiments carried out confirmed the effectiveness of this method. In Gymnasium No. 271 (St. Petersburg) in the first grade all children learn Esperanto, and from the second - French (Esperanto remains an elective in the middle classes).

- Business language.

There are examples of the successful use of Esperanto in commerce, in the implementation of major international projects (in particular, the creation of multilingual sites on the Internet, the development of IP-telephony, the organization of international tourism, and so on).

- Politics and propaganda.

During the Cold War era, Esperanto was actively used by the countries of the socialist camp (China, Hungary, Bulgaria, to a lesser extent Poland and the USSR) to promote socialism. For example, the famous “Red Book” (Mao's quotation book) was published in Esperanto, many of Lenin's works were published, periodicals about life in the PRC, the USSR and other countries were published. Cuba and China continue to broadcast regular shortwave programs in Esperanto to this day. In China, there are regularly updated information sites in Esperanto, such as http://esperanto.cri.com.cn and others.

Grammar

Valid

Passive

Future

Ont-

present tense

Ant-

Past tense

Int-

Degrees of comparison of adverbs and adjectives

The degrees of comparison are conveyed by additional words. Comparative degree - pli (more), malpli (less), excellent - la plej (most) (for example, important - grava, more important - pli grava, most important - la plej grava).

Pronouns and pronominal adverbs

Another convenient system in Esperanto involves the connection of pronouns and some adverbs by dividing them into structural elements.

quality | causes | time | places | image | direction- leniya | belong- bedtime | subject | quantities | faces |

|

indefinite | ||||||||||

collective | ĉia | ĉial | ĉiam | eie | ĉiel | ĉien | ĉies | Geo | ĉiom | ĉiu |

interrogative | kial | kiam | kiel | Kien | kies | kiom | ||||

negative | nenia | neial | neniam | nenie | neniel | nenien | nenies | neonio | neniom | neniu |

index | tial | tiam | tiel | Tien | ties | thyom |

Flexible word-formation system

Perhaps the main success of Esperanto is its flexible word-formation system. The language contains several dozenprefixes And suffixes , having a constant value and allowing to form from a small numberroots many new words.

Here are some of suffixes :

-et - diminutive suffix

-eg - augmentative suffix,

-ar - a suffix denoting a set of objects,

-il - suffix denoting instrument,

-ul - suffix of a person, creature,

-i - a modern suffix for designating countries.

With the help of these suffixes, it is possible to form words from the roots arb-, dom-, skrib-, bel-, rus- (tree-, house-, pis-, kras-, russ-):

arbeto - tree,

arbaro - forest,

domego - house,

skribilo - pen (or pencil);,

belulo - handsome

Rusio - Russia.

There are also, for example, suffixes that make it possible to form the names of fruit trees from the names of fruits ( piro "pear", pirujo “pear (tree)”), part of the whole (-er-), thing; there are prefixes with the meanings “kinship through marriage” (bo-), “both sexes” (ge-), an antonym to this word (mal-).

Diacritics set

Specifically Esperanto letters with "lids" (diacritics ) are not found in standard Windows keyboard layouts, which led to the creation of special programs for quickly typing these letters (Ek! , addition to firefox abcTajpu , macros for Microsoft Word , custom keyboard layouts, and others). There are Esperanto layouts underlinux : specifically in the standard distributionubuntu . Most Internet sites (including the Esperanto section of Wikipedia) automatically convert characters with x's typed in postpositions (x is not included in the Esperanto alphabet and can be considered as a service character) into characters with diacritics (for example, from the combination jx turns out ĵ ). Similar typing systems with diacritics (two consecutively pressed keys type one character) exist in keyboard layouts for other languages as well, such as the "Canadian multilingual" layout for typing French diacritics. A letter can also be used instead of a diacritic. h in postposition (Zamenhof advised this alternative notation in the first language textbook: "Printing houses that do not have the letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ may initially use ch, gh, hh, jh, sh, u”), but this method makes the spelling non-phonemic and makes automatic sorting and transcoding difficult. With the spreadUnicode this method (as well as others, such as diacritics in postposition - g'o, g^o and the like) is less and less common in Esperanto texts.

Basic language facts

Esperanto is intended to serve as a universal international language, the second (after the native) for every educated person. It is assumed that the presence of a neutral (non-ethnic) and easy-to-learn language could bring interlingual contacts to a qualitatively new level. In addition, Esperanto has a large- greatly facilitates the subsequent study of other languages.

Alphabet and reading

Alphabet Esperanto is based onLatin . Alphabetically 28 letters : A, B, C, Ĉ, D, E, F, G, Ĝ, H, Ĥ, I, J, Ĵ, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, S, Ŝ, T, U , Ŭ, V, Z (special letters addedĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ; graphemes q, w, x, y are not included in the Esperanto alphabet), which correspond to 28 sounds - five vowels, two semivowels and 21 consonants. In the alphabet, letters are called like this: consonants - consonant + o, vowels - just a vowel: A - a, B-bo C - co and so on.

Each letter corresponds to one sound (phonemic letter). The reading of a letter does not depend on the position in the word (in particular, voiced consonants at the end of a word are not stunned, unstressed vowels are not reduced). Stress in words is fixed - it always falls on the second syllable from the end (the last syllable of the stem). The pronunciation of many letters can be assumed without special training (M, N, K and others), the pronunciation of others must be remembered:

- C(co ) is pronounced like Russian c: centro, sceno [scene], caro [tsaro] "king",

- Ĉ (ĉo ) is pronounced like Russian h: ĉefo "chief", "head"; ,

- G (go ) is always read as g: grupo, geografio [geographic],

- Ĝ (ĝo) African , pronounced like a slur jj (as in the quickly pronounced word "jungle"), it does not have an exact match in Russian: Cardeno [giardeno] - garden, etaco [etajo] "floor",

- H(ho ) is pronounced as a voiceless overtone (English h): horizonto , sometimes as Ukrainian or South Russian "g",

- Ĥ (ĥo ) is pronounced like Russian x:ĥameleono, ĥirurgo, ĥolero,

- J (jo) - like Russian th: jaguaro, jam "already",

- Ĵ (ĵo) - Russian f: ĵargono, ĵaluzo "jealousy", ĵurnalisto,

- L (lo) - neutral l (the wide boundaries of this phoneme make it possible to pronounce it like the Russian “soft l”),

- Ŝ (ŝo) - Russian sh: ŝi - she, ŝablono,

- Ŭ (ŭo ) - short y corresponding to English w and modern Polish ł; in Russian it is heard in the words "pause", "howitzer": paŭzo [paўzo], Eŭropo [europo] "Europe". This letter is a semivowel and does not form a syllable.

From the history of Esperanto